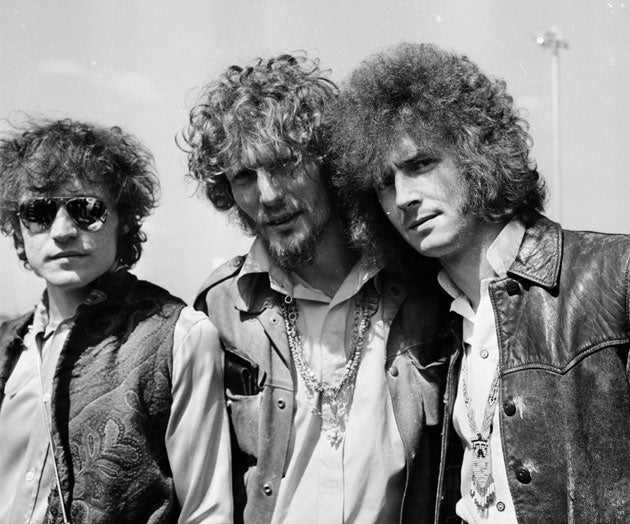

Ginger Baker: Drum cat who got the Cream

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even if you missed growing up in the 1960s, you're bound to have heard Ginger Baker's explosive drumming with the rock bands Cream and Blind Faith. In both beat combos, Baker was an amazing sight.

His kit featured two bass drums, tuned slightly differently, so that he could play counter-rhythms with both feet, while his hands belaboured the snare, toms and cymbals. His arms flailed; his wild red hair shook like a Celtic warlord's. He was, rumour had it, the most truculent of rock stars, handy with both verbals and fists; while his Cream co-members, Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce, were mostly cool and understated, he was mysteriously agitated, bug-eyed and feral, like a pissed-off wizard.

Some reasons for his rage can be found in his book, modestly titled Hellraiser, The Autobiography of the World's Greatest Drummer, out this week. It's the story (partly ghosted by his daughter, Ginette) of a wartime London kid, raised in Eltham, who didn't shine at school but discovered he had a God-given flair for percussion, who flourished in half a dozen Fifties jazz bands, achieved massive if short-lived fame in the rock'n'roll Sixties, injected tidal waves of dangerous narcotics, enjoyed the company of numerous "tasty chicks" (and one famous university professor) and found peace on horseback in early middle age.

At a hotel in West London, Ginette ushers me into the bedroom, where Ginger Baker, now 70, is in jeans, shades, a violently floral shirt and a mid-morning grump. The duvet is piled up behind him, suggesting he's been through a night of frantic sex or terrible dreams. He chain-smokes and groans one-word replies until we hit the subject of war.

He was born the year it broke out, and he loved it. "People get the wrong impression of the effect the war had on kids, particularly boys," he said. "It was very exciting." He loved explosions. A jazz drummer was born.

His bricklayer father was killed in action in 1943 when Ginger was four, and he was brought up in near-poverty by his mother, stepfather and aunt. Baker was always in trouble. He stole records, joined a gang, was attacked with a razor. His sole amusement was cycling, until he discovered something he was really good at.

"I was always tapping and banging at things when I was young," he says. "We used to go to all the jazz clubs, like the Hot Club in Woolwich. I'd go to watch the drummers, like Lennie Hastings, and try to learn from them. At this party, there was a little band and all the kids chanted at me, 'play the drums!'. I'd never sat behind a kit before, but I sat down – and I could play! One of the musicians turned round and said, 'bloody hell, we've got a drummer', and I thought, 'bloody hell, I'm a drummer'."

Soon he was playing jazz gigs in Gladstone Park and Wembley. Contriving to fail his National Service, he hung out at the Star Café in Soho, meeting the likes of John McLaughlin and his hero Phil Seamen. His teen years were a dizzying round of gigs, drinking, fights with police, crashing cars, discovering marijuana and smack, and falling for his first love, Liz Finch, whom he married in 1959 when they were both 20. It was also the period when he learned to sight-read notation and devour guides to song arrangement, like Basic Harmony and The Schillinger System. It's a constant refrain in his conversation that he isn't just a drummer, thanks a lot, but a Real Musician.

When the Sixties pop era arrived, Baker was playing complex rhythms with Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated and the Graham Bond Organisation. Also, heroin was making him, in his words, "an obnoxious little git". He didn't have much time for the 4/4 beats of the pop world. In the book, he cites Charlie Watts and Pete Townshend as "proper musicians," but doesn't mention The Beatles. Hadn't he admired Ringo Starr's drum style?

"HAH!" Baker lets out a roar of delight, or possibly pain, at the idea. "They weren't musicians!" he says, drying his eyes. "I worked with George Harrison and he was a musical moron. He didn't understand music at all. He tried to explain what he wanted, and I couldn't understand a word. The only musician was George Martin, he was The Beatles. Paul McCartney boasts that he can't read music. How can a musician boast that he can't read music?" Baker's rant is delivered with the certainty of a man who put in the hours studying Bach and Mozart. He is just as dismissive of other sacred monsters of the time. "Mick Jagger and Brian Jones were playing at the Ealing Club, and Alexis asked us to play behind them for the interval. We weren't very happy, so we played complicated time things to throw Mick off the beat. He would lose it completely and Brian would have to get him back on. Mick Jagger got everything from him. The original sound of the Stones was Brian Jones leaping about and doing all the showmanship. Jagger just stood there at the microphone."

And when they became the world's greatest rock band? "I never could stand the Stones," said Baker. "They were like a load of little kids trying to play black blues music and playing it very badly – but that's what people went for, because it was naive and banal. The lack of technique and musicianship was its appeal, from the start. It was extremely commercial, musically. The guitarist, Keith, sometimes has a go at Eric [Clapton]. but Eric is 150,000 times better a musician than he'll ever be. But because of their fame and fortune, they believe they're special."

Even the sainted Jimi Hendrix gets a telling-off. He sat in at a gig at London Polytechnic in 1966 and greatly impressed Clapton. Sounding distinctly Scrooge-like, Baker reports: "Hendrix could play okay. But he started doing all this showman shit when he sat in with us. If I had to choose a guitarist from history, I'd pick Eric over Jimi every time. Jimi was good but he was too interested in that... stuff. His big thing was pulling chicks, which he was very good at."

Despite his lack of matinee-idol looks, Baker himself is no slouch in the chicks department. As the book records, he picks up willing bedmates across the globe, from Nigeria (interrupted by an irate Tuareg husband) to California, where he met his third wife, Karen. At a 1969 BBC concert in Shepherds Bush, he caught the eye of Germaine Greer, then 30, in the audience. Unaware that he was pulling the about-to-be-published author of The Female Eunuch, he took her home.

"She wasn't kinky at all." Baker reports. What, she didn't want to be tied up? Or dominated? How extraordinary. "I mean she didn't want any... kinky stuff," said Baker, circumspectly. "Just straight, normal, man and woman... She's a really nice girl, Germaine. I've always thought the world of her."

Hellraiser features Baker's attempts to "set the record straight" about the formation of Cream. Baker and Jack Bruce, the bassist, first met in the Jazz Marquee at the Cambridge May Ball in 1962. They played together in the Graham Bond Organisation, but cracks soon began to show. At a gig in Golders Green, Bruce joined in a Baker drum solo, then interrupted it by shouting "You're playing too loud, man!" and a fist-fight broke out. Baker was later deputed to tell him he was fired from the band. Baker and Clapton met in 1966 at a university gig, when Clapton was playing with the Yardbirds. Impressed by Clapton's playing, Baker met him in Oxford and said, "I'm getting a band together. Would you be interested?" Clapton agreed. His nomination for a bassist was Bruce, whom Baker had fired years before, but Ginger decided to give the stroppy Glaswegian another chance. Bruce has a different version of the story, and a strong whiff of bile and rancour comes off the pages whenever his name comes up.

"He thinks I'm a wonderful drummer, but ignores the fact that I'm a musician," says Baker. "Jack's got an ego problem. He thinks he was the musical genius behind Cream. But all the arrangements Cream played were by me." What rankles with Baker is that some of the band's classic songs (like "White Room" and "Politician") are credited to "Bruce/Brown" – Jack Bruce and Pete Brown, a performance poet whom Baker invited in to write lyrics – ignoring the vital contribution of guitarist and drummer.

By the time Cream broke up in 1969, they'd sold 15 million records and played a key role in the birth of heavy metal. Baker and Clapton formed the brilliant but short-lived Blind Faith, with Stevie Winwood from Traffic and Ric Grech from Family. Post-Faith, Baker moved restlessly in and out of bands – Air Force, Hawkwind, the Baker-Gurvitz Army – travelled in Africa (he now lives in the Western Cape) married twice more and discovered polo. Until this epiphany, the most intense obsession of his life, after drumming, was drugs.

The book is a chronicle of drug ingestion. He was doing class-A in massive quantities for 31 years, "but I came off 29 different times. Coke is terrible stuff. Several times I've thrown a large amount down the toilet, then, two hours later, I'm saying, 'I wish I hadn't done that'." Had he been able to play while tripping? "I could always play, whether I was totally pissed or totally stoned. You either got it or you haven't." And that, all through his life, is the burden of Baker's song: he always had the talent and musicianship, while around him musical morons came and went and he never received the recognition he craved. Even on the last page, he's still complaining, about the Zildjan Drum Awards in 2008, in which the programme suggested that the epitome of British rock drummer was John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, because he fused the styles of Keith Moon, Mitch Mitchell and Ginger Baker. "Absolute rubbish!", cries Baker.

The book is a fantastic tirade of drugs, guns, trouble, crashes and violence. How have you managed to live so long? "It's miraculous," says Baker gleefully. "They put me in the Playboy Dead Band in 1972 with Janis Joplin, Greg Allman, Jimi Hendrix. I was reported dead several times – once when I was driving a Shelby Cobra with three tasty chicks, and the radio station announced I was found dead in my hotel room from a heroin overdose." He takes a drag on his eleventh cigarette, then yells: "Oi! Any chance of some more tea?"

'Hellraiser: The Autobiography of the World's Greatest Drummer by Ginger Baker' is published by John Blake, price £18.99.

The Ginger Baker story

1962: Graham Bond Organisation Dirty sounding R'n'B with Bond on organ and Jack Bruce on double bass

1966: Cream with Eric Clapton on guitar and Bruce on bass

1969: Blind Faith blues-rock band with Clapton, Steve Winwood and Ric Grech

1969: Ginger Baker's Air Force jazz-rock-fusion with Winwood on organ and Grech on violin and bass

1972: 'Stratavarious' album recorded with Fela Kuti and Bobby Tench (from the Jeff Beck Group)

1974: Baker Gurvitz Army hard rock trio with Paul and Adrian Gurvitz

1991: 'Unseen Rain' a free-form instrumental album

1994: Ginger Baker Trio free jazz

1994: BBM power trio with Bruce and Gary Moore on guitar

1999: 'Coward of the County' album with jazz trumpeter Ron Miles

2001 & 2006: 'African Force ITM' and 'Palanquin's Pole' albums mixing African and Western influences

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments