‘We’re The Beatles, we’ve got the grooves and you two are just watching’: how George Harrison refused to be kept down by Lennon and McCartney

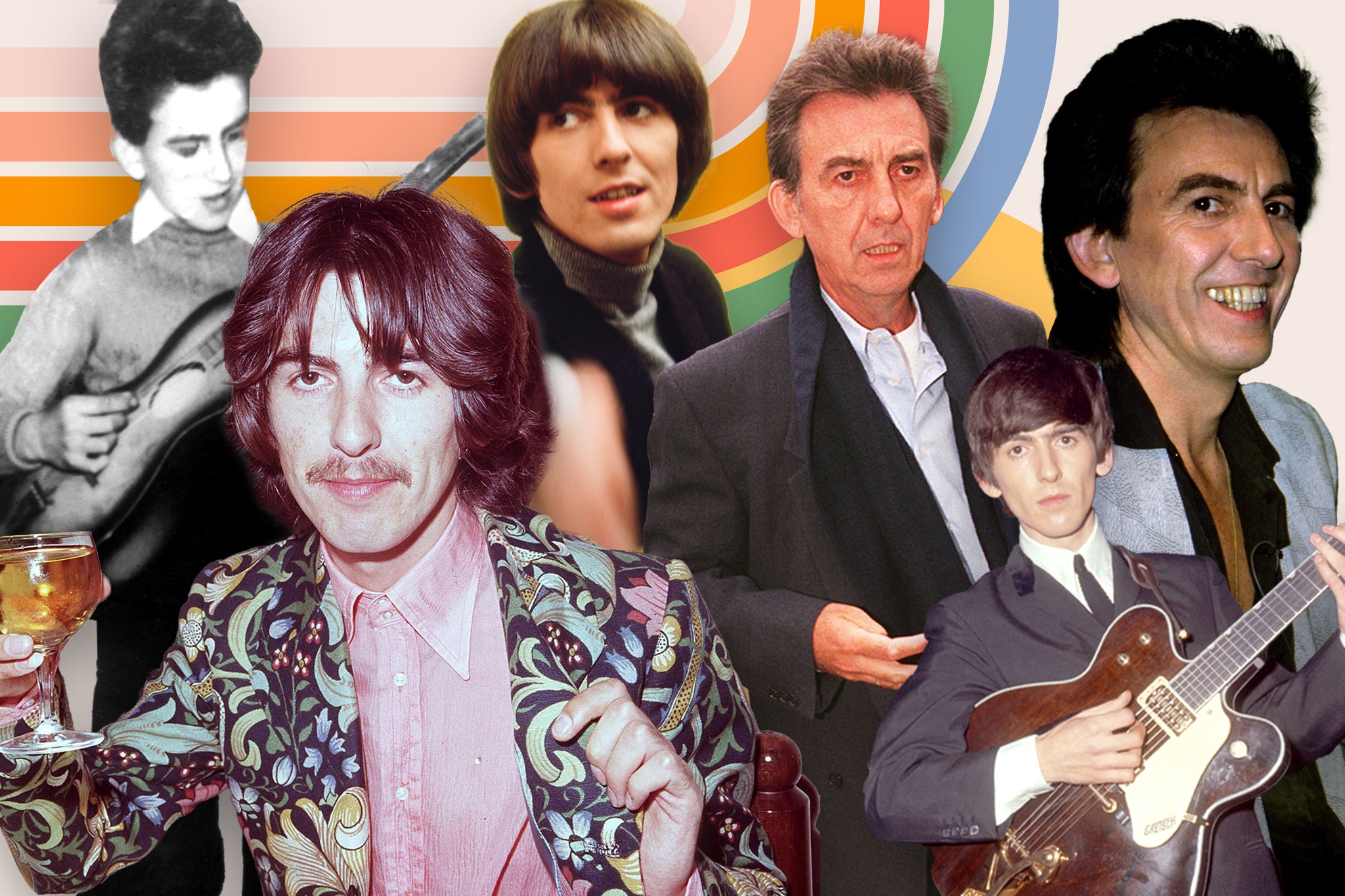

A major new biography of the revolutionary guitarist and self-professed ‘economy-class Beatle’ delves deep into the seven years of seething acquiescence George Harrison endured as his songs were crushed by the Lennon-McCartney juggernaut, writes Mark Beaumont. In the end, the break-up of the band was his saving – and their loss

It was arguably rock’n’roll’s most brutal and historic piece of passive aggression. Midway through The Beatles’ umpteenth rehearsal attempt to nail down “Two of Us”, the song destined to open 1970’s Let It Be album, George Harrison grew frustrated at Paul McCartney’s overbearing direction, and subtly cracked. “I’ll play whatever you want me to play, or I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to play,” Harrison placidly intoned, steely and faux-subservient. “Whatever it is that will please you, I’ll do it.”

Seething behind those seemingly innocuous words – captured on film as part of the Let It Be project, in which the fracturing Beatles attempted to write an album on camera – lurked seven years of resentment on the part of the most underrated Beatle. Seven years of having his songcraft crushed beneath the wheels of Lennon and McCartney’s hit-making juggernaut. Of exclusion from the band’s creative hierarchy, borderline insulting publishing splits and fighting to the point of exhaustion for his songs to be heard, let alone recorded. A resentment that would soon play a significant role in tearing the world’s greatest band apart.

“George would not be kept down,” says author Philip Norman, author of a new Harrison biography George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle. It adroitly traces the sidelining of this self-proclaimed “economy-class Beatle” right up to the fracture point where, as Harrison himself explained, “We’d have to record maybe eight of their [songs] before they’d listen to mine.” The insecurity and lack of confidence Harrison displays when presenting songs as strong as “Something” to the band in The Beatles: Get Back was the result of a deep-rooted underappreciation. As late as one of the band’s last ever meetings, in September 1969, McCartney confessed that, until Abbey Road, he felt Harrison’s songs – “Taxman”, “If I Needed Someone”, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”, remember – simply “weren’t that good”.

The Reluctant Beatle, on the other hand, makes a case for Harrison, not just as one of the most revolutionary guitarists of the Sixties, but one of their finest songwriters too. In “Something”, “While My Guitar…”, “Here Comes the Sun” and others, he produced some of The Beatles’ best songs and, by logical extension, some of the greatest ever written. Norman also explores Harrison’s role as a catalyst for many of the band’s – and the era’s – most seismic cultural shifts.

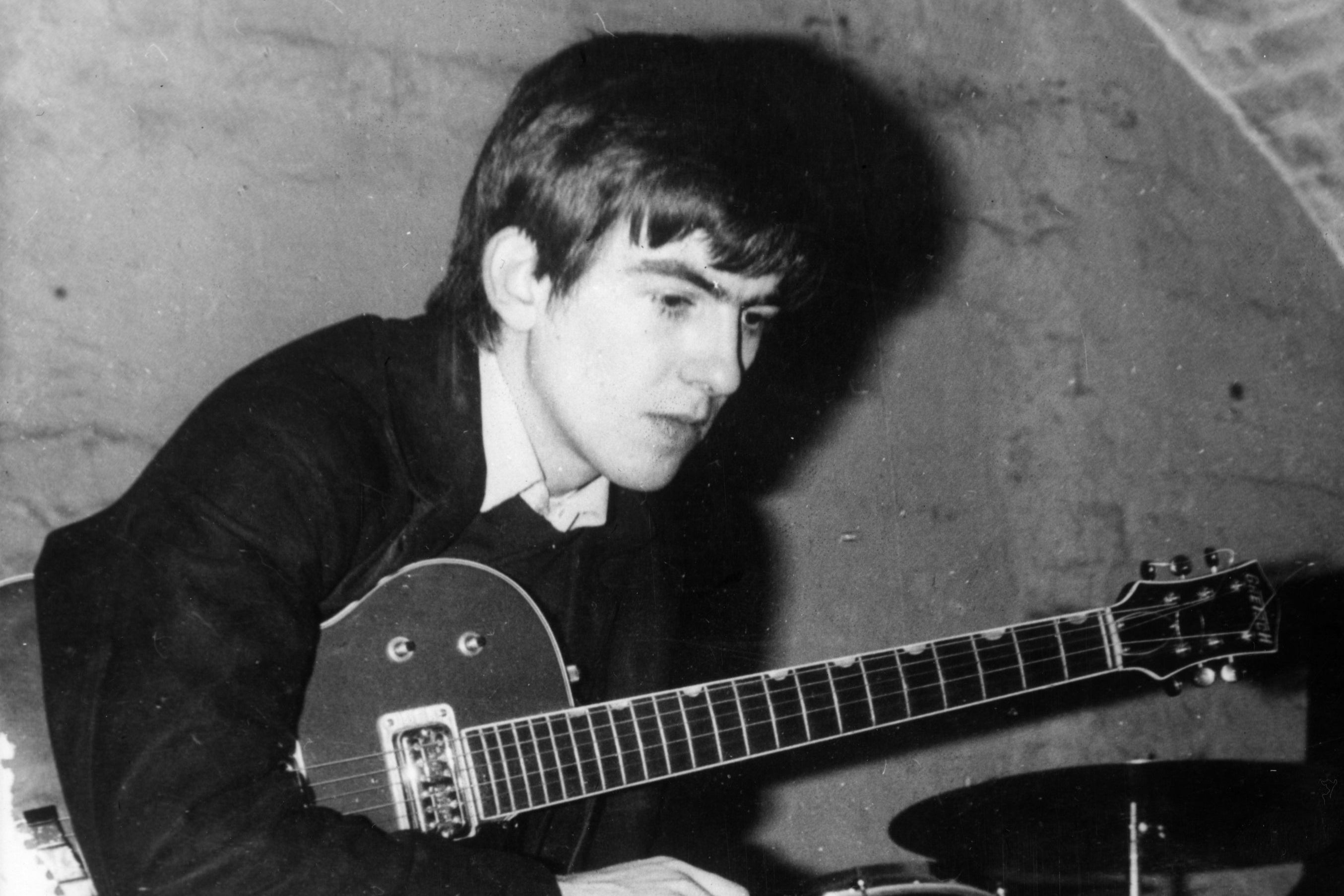

It was Harrison’s mystery “CLANG!” chord at the beginning of “A Hard Day’s Night” that epitomised Beatlemania. His experimental second solo album Electronic Sound (1969), in avant-garde fashion, exposed mainstream audiences to the sci-fi sizzle of the synthesiser. His immersion into Indian and Eastern music, culture and thinking – having been exposed to such sounds and ideas while filming 1965’s Help! movie – helped provide the aesthetic and philosophical bedrock for late-Sixties hippie counter-culture. What’s more, Harrison’s sitar and raga work is widely credited with awakening the Western world to the appeal and possibility of global music. And that’s before you even get to the oxyacetylene riff from “And Your Bird Can Sing”.

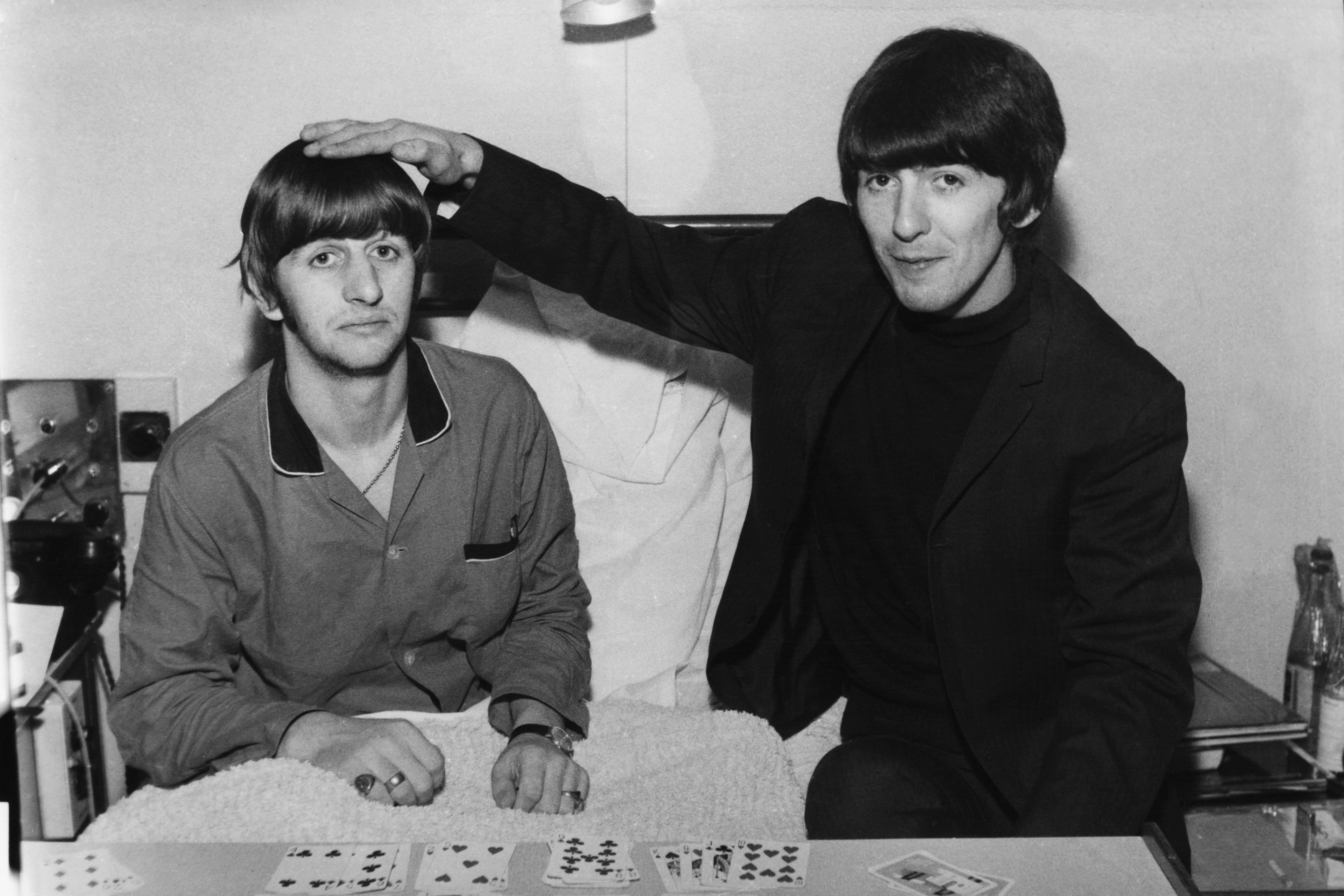

Norman highlights further fascinating claims of Harrison’s pivotal influence on the decade. It was he, it turns out, who tipped off Decca A&R man Dick Rowe – who’d previously passed on signing The Beatles after their legendary 1962 audition for the label – to the next next big thing: The Rolling Stones. He was key in ousting drummer Pete Best in favour of Ringo, and got a black eye from an aggrieved Cavern fan as a result. He helped make early bassist Stuart Sutcliffe and his German partner Astrid Kirchherr’s existentialist art “mop-top” hairstyles a band-wide phenomenon; primarily wrote the first song the band ever recorded in Hamburg (“Cry for a Shadow”); and was an instrumental voice in stopping the band touring following their chaotic world tour of 1966. Thereby facilitating the culture-quake studio innovations of Sgt Pepper… and beyond.

At all stages of The Beatles’ ascent, Harrison changed history. By pursuing his fascination with Eastern music and philosophy as far as the Maharishi’s Transcendental Meditation retreat in Rishikesh, in the foothills of the Indian Himalayas, his bandmates and thus popular culture in tow, Harrison unwittingly instigated the band’s most prolific and rewarding late-period writing splurge (much to his own annoyance; he was there to meditate). And in the book, Lennon’s art school friend Bill Harry even credits Harrison with launching the band in the first place, by reforming a dislocated Quarrymen line-up to play the opening night of Liverpool’s Casbah Club in 1959. “That really was where The Beatles began,” he says.

Rather than the shy, retiring “Quiet One” of pop mag legend, a deeper, more conflicted portrait of this teenage Teddy Boy rebel from Liverpool’s slaughterhouse district emerges from the book. His understanding, generous and down-to-earth side is evident in testimonies unearthed from ex-lover Estelle Bennett of The Ronettes and his old school band chum Arthur Kelly, who turned up at Harrison’s house at the height of Beatlemania to be welcomed into The Beatles’ world and gifted six suits left over from the guitarist’s Help! shoot wardrobe. At various points, Harrison’s open-door policy to life results in a family of Californian hippies living undetected in an unused Apple office and a squadron of Hell’s Angels, at George’s invitation, taking up residency in the company’s Savile Row HQ and causing drug-crazed, Christmas turkey-based havoc.

I’m not sure they ever quite shook that feeling of him being the junior member

There was also an irritable, temperamental and brusque aspect to the young guitarist, who almost throttled the band’s career at birth by insulting producer George Martin’s tie on first meeting, and who once rushed Princess Margaret out of a formal occasion with the words “Ma’am, we’re starved and we can’t eat until you leave”. “George was very nice,” Yoko Ono said of him, “but he was sometimes very frank and it could be very hurtful.”

“He had two different personalities that could change from one to the other in an instant,” Starr would explain. “There was the love and bag-of-beads personality and the bag of anger.” As someone who had kicked back against the authoritarianism of his state school by creating his own Teddy Boy version of its starched uniform, Harrison was particularly irked by anything that acted against his fundamental enjoyment of Beatle life – he was first to admit that fame and money hadn’t bought him happiness and to pursue a more spiritual path, for instance. He was the same about anything that confined him.

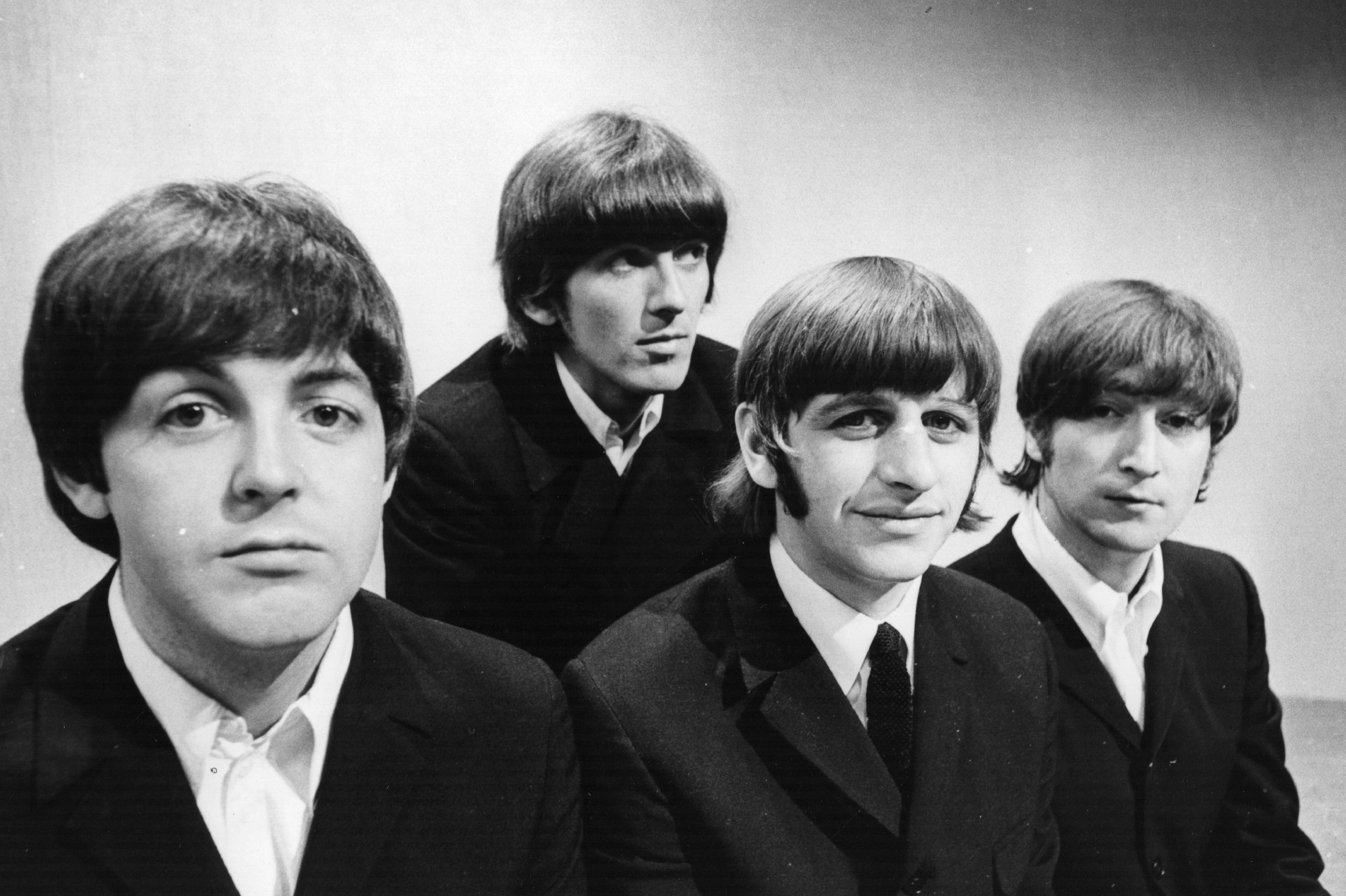

Chief among such strangleholds was his lowly status in The Beatles’ creative pecking order. Of course, no matter how handy you are with a skiffle-pop tune, landing up in a band with the two greatest songwriters of all time will understandably involve a certain acquiescence and puncturing of ego. “The people who wrote the songs were John Lennon and Paul McCartney and they were both geniuses and pretty dominant personalities,” says Graeme Thomson, author of George Harrison: Behind the Locked Door. “The two other people shine so bright that it’s inevitable he’s not going to share that degree of prominence.”

But biographers point to Harrison’s relative youth, joining the band when he was just 14, installing a fatal flaw in The Beatles from its inception. “I’m not sure they ever quite shook that feeling of him being the junior member,” says Thomson, “not in an unpleasant way but they were doing the real work and they were so driven, especially McCartney… I don’t think they were that interested in what other people were writing, they were so interested in their own work.”

Norman writes of the teenage Harrison feeling left out of Lennon and Sutcliffe’s intellectual discussions in Hamburg, and the intense songwriting bond between John and Paul. He also cites George Martin’s fascination with the prolific brilliance of the Lennon and McCartney partnership in undervaluing Harrison from their earliest sessions. Producing their very first single, “Love Me Do”, Martin cut Harrison’s solo in favour of a harmonica part, a sign of things to come. “Martin never really looked at George except to basically instruct him what to play as his solo,” Norman says. “Martin himself said, ‘I was always rather beastly to George.’”

On The Beatles’ 1963 debut album, Please Please Me, Harrison was given lead vocal on “Do You Want to Know a Secret” because, according to Lennon, “It only had three notes and [George] wasn’t the best singer in the band”. His sole writing credit on 1964’s follow-up With the Beatles was “Don’t Bother Me”, arguably a disgruntled reaction to Lennon and McCartney raking in the bulk of the songwriting royalties from their initial whirlwind success via their Northern Songs publishing contract, of which his cut was a desultory 0.8 per cent (he’d later write “Only a Northern Song” in complaint). On an early-Sixties trip to visit his sister in Illinois, Harrison gifted 16 of his unused songs to the bassist of an unknown band called The Four Vests, convinced he’d have no use for them.

He was going on about how hard done by he felt because of only having two songs on [Abbey Road]... Even two songs like ‘Here Comes the Sun’ and ‘Something’

“A kind of attitude came over,” Harrison said of a band dynamic dominated by such a phenomenally talented duo. “We’re The Beatles, we’ve [got] the grooves and you two are just watching.”

Along the line, Harrison would grow bored of his limited involvement in Sgt Pepper… and was given virtually nothing to do in McCartney’s pet TV movie project Magical Mystery Tour. “He refers to himself as an ‘appendage’ to that,” Norman says. And despite contributing such culturally influential and musically spectacular songs as “Taxman”, “If I Needed Someone” and “Love You To” to evolutionary mid-period albums Rubber Soul and Revolver, Harrison struggled to get the respect he deserved as a songwriter throughout the band’s lifespan.

While recording The White Album, they allegedly paid little attention to his first real masterpiece “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” until he invited his friend Eric Clapton to the studio to play on it. So dented was his confidence that he set aside “Something” for months because he was convinced someone else must have written it first.

Harrison’s creative frustration finally boiled over during the Get Back sessions. Amid alleged fisticuffs, he quit the band midway through with the words “see you round the clubs”, and was only convinced to rejoin if the Let It Be project continued on terms he dictated. Yet, even when playing Bob Dylan an acetate of Abbey Road during Dylan’s visit to the UK to play the 1969 Isle of Wight festival, Harrison remained disgruntled. “He was going on about how hard done by he felt because of only having two songs on the album,” said the festival’s founder Ray Foulk. “Even two songs like ‘Here Comes the Sun’ and ‘Something’.”

This dissatisfaction was a key element in The Beatles’ disintegration, but Harrison arguably got the last laugh. His 1970 solo album All Things Must Pass – a triple, consisting largely of songs rejected by The Beatles or never even played to them – significantly outsold Lennon and McCartney’s early solo records and ruthlessly exposed the injustice of his subjugation within The Beatles to awestruck critics. “The end of The Beatles was considered a huge tragedy by the generation that grew up with them,” says Norman, “but it was the best thing that could’ve happened to George.” In hindsight, his bandmates must have kicked themselves at not knowing what they had ’til it was gone.

‘George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle’ is available now, published by Simon & Schuster

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks