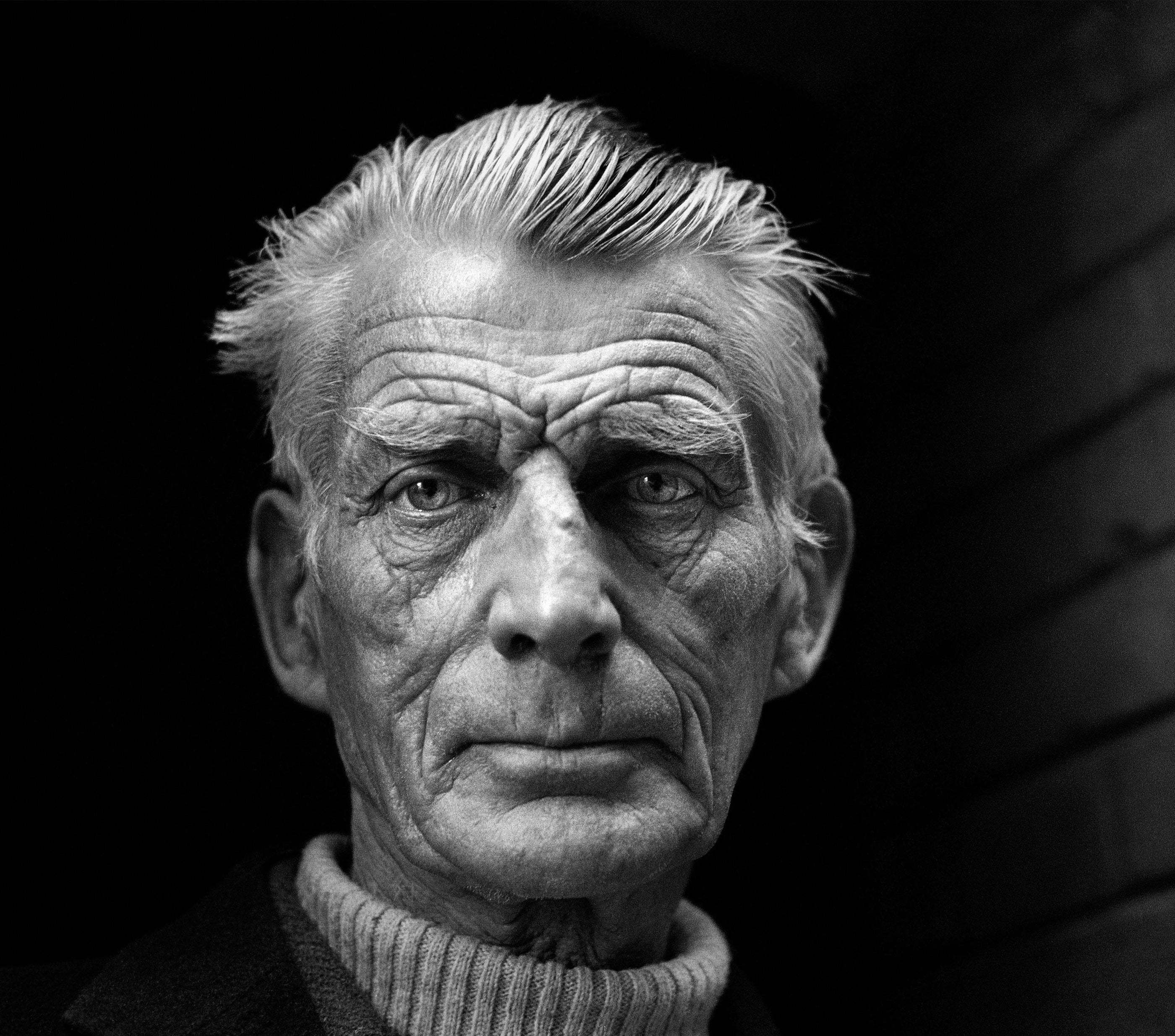

Gavin Bryars on Samuel Beckett: 'There is something particularly satisfying about devoting a collection of songs to a single poet'

I was in my teens when I first came across Waiting for Godot in Goole Public Library

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I started to set Samuel Beckett’s poetry to music two years ago when I was commissioned to write four songs for the first Happy Days Festival held in Enniskillen. Having written these four songs I resolved to do more and, eventually, to have a Beckett Songbook.

There is something particularly satisfying about devoting a collection of songs to a single poet, like Hugo Wolf with his Mörike lieder, or Schumann’s Dichterliebe with its sequence of poems by Heinrich Heine; and I already have two “songbooks”, setting both Etel Adnan and Blake Morrison.

Beckett has been of great importance to me for many years. I was in my teens when I first came across Waiting for Godot in Goole Public Library, along with the novels Murphy and Watt – and I found other Irish writers there, too. When I went to Sheffield University I was overwhelmed by having unrestricted access to the comprehensive and coherent collections of a large library, and I spent my entire first term reading nothing but complete editions of Irish plays: Shaw, Wilde, O’Casey, Synge, Behan, Beckett.

There are personal connections to Beckett, too. I worked as a jazz and improvising bass player with the guitarist Derek Bailey, who looked remarkably like Beckett and even cultivated particular Beckett poses for photographs (and people were unsure whose was the photograph on my mantelpiece). Later I worked closely with Beckett’s friend and theatre designer Jocelyn Herbert at the Leicester Haymarket Theatre on a number of plays, including Simon Usher’s ingenious Timon of Athens, where she produced everything for 50 per cent of her budget. I also saw her work on the studio production of Krapp’s Last Tape with the extraordinary David Warrilow. My Beckett Songbook is dedicated to Jocelyn.

In the last few years, through working on various Irish source materials, I eventually came back to Beckett. The first stage in this journey was when I spent some time setting Petrarch. In the bibliography of Robert Durling’s edition of Petrarch’s Rime Sparse, there is a reference to the “remarkable Irish prose translations” by John Millington Synge, which I eventually set. These translations are closely linked to his dramatic work, serving as a kind of experiment in the prose poetry that he would employ in his last play, Deirdre of the Sorrows – indeed, Deirdre’s closing monologue is almost pure Petrarch. But having spent some time setting Petrarch in Italian, Synge’s Irish texts seemed initially quite difficult and awkward.

Lines such as: “What new light is that? What new beauty at all? The like of herself hasn’t risen up these long years from the common world.”

But eventually these quasi-circumlocutions took on greater emotional force and I can see why, as I learned later from James Knowlson’s biography, Beckett revered Synge above almost any other writer.

There are many elements in this journey through Irish literature that sustain my work on a Beckett Songbook. One of these is the idea of working between two languages, like Synge, in a way that is not just translation. I was aware that Beckett wrote many works in French, including Waiting for Godot, before eventually making English versions. Of the first four poems that I set, three also exist in French. While it is true that translated poems can take on a new life when translated by another poet, it is surely unique for this situation to pertain within a single author’s work. And the interesting thing is that these are not really translations – in either direction (though they can be) – but are more often poems that share the same imagery and subject, and may contain equivalent metaphors, but can be very different.

While the first line of “je suis ce cours de sable qui glisse”, for example, is clearly recognisable in its English form “My way is in the sand flowing”, there is something mysteriously oblique about “Something there” being “hors crâne”. (In the commentary to the Collected Poems we are told that Beckett referred to the two versions as being “one little poem in French... and a rather dimmer companion in English”). Later this year I will add the four French versions of the English ones I’ve already set to complete the 11 pieces for the Beckett Songbook.

I decided to set all the poems for two voices – soprano and counter tenor – rather than just one. It seemed that this duality reflected the appearance several times of an implied question and answer from one line to another. In “Dread Nay”, which only exists in English, I used the same device for the rapid sequence of very short lines. It also followed a technique that I had used in the cantata The War in Heaven, setting a text by Sam Shepard, where a narrative sequence has the two singers alternating lines, like the convention of a male and female TV newsreader completing each others’ lines.

For this year’s Happy Days festival, in addition to English settings of seven of Beckett’s poems, I will also perform ten of the 17 Irish Madrigals (Synge Petrarch), a group of Gaelic songs from the Ánail Dé project with Iarla O’Lionaird that we began ten years ago after a performance of my Synge settings in Dublin, as well as an ensemble version of “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet”, where the frail recorded voice of an old man sits quite comfortably in a Beckett environment.

Gavin Bryars is composer-in-residence of Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival, Enniskillen (www.happy-days-enniskillen.com) 31 July to 10 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments