Future Islands’ Samuel T Herring: ‘It’s taken me six years to come to terms with Letterman’

The Baltimore band went viral thanks to Herring’s performance on the US chat show but they’ve finally moved on with a new album about self-acceptance and heartbreak, the frontman tells Ellie Harrison

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I knew exactly what I was doing,” says Future Islands frontman Samuel T Herring, reflecting on the performance that changed his life. “Lots of people said: ‘This guy dances like nobody’s watching.’ But no. I was dancing like I knew everyone was watching.”

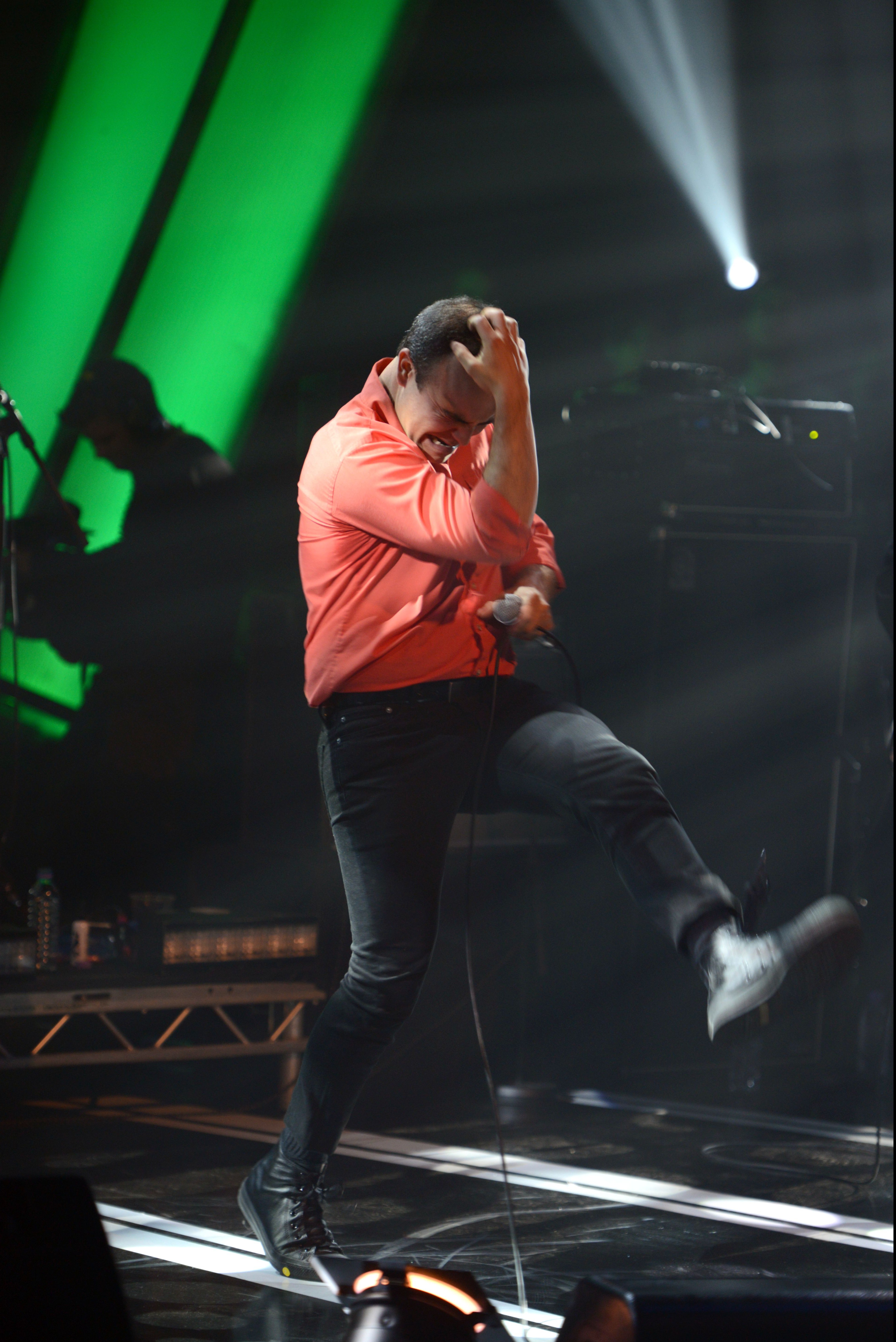

In March 2014, Future Islands played their song “Seasons (Waiting on You)” on US chat programme The Late Show with David Letterman. Herring, whose singing oscillates between a stately tremble and a death-metal growl, performed the chest-thumping anthem with an urgency that transfixed the internet. In the clip, which has been viewed 3.3 million times, the stocky singer squats, jumps and rocks across the stage as the music seems to take control of his muscles. “I was actually holding back,” the 36-year-old tells me now. “That’s what was going on in my head – don’t go too far.”

The performance, which coincided with the release of their fourth album, Singles, catapulted Future Islands into the big league, earning them fans such as Bono – who shipped them a case of Guinness after seeing it – and Debbie Harry, who later collaborated with the band. And it established Herring as an improbable yet charismatic, vaudevillian showman, who boldly blurred the lines of indie, rock and pop.

But Future Islands had been around long before that. They formed in Baltimore in 2006 and had played around 800 shows and released three albums before Letterman. The group – consisting of lyricist and singer Herring, keyboardist and programmer Gerrit Welmers, bassist William Cashion and drummer Michael Lowry – have been described as “one of the planet’s most uplifting bands”, their synth-pop songs pulsing with hope. But they can also be bluesy and plaintive, with Herring’s gruff voice catching on certain words, his pain lurking in a lump in his throat.

“It’s taken me six years to come to terms with Letterman,” says Herring over Zoom from Stockholm, where he’s staying with his partner. “People saw us as this overnight success but I didn’t want to be seen that way. We were ready for that moment.”

The “meme-ification” of the event, he says, was difficult to deal with and he found himself focusing on negative comments online. “One person said, ‘Is he whizzing himself?’” Herring laughs, a twinge of hurt in his voice. “These days, you’re bombarded with what everybody else thinks. It can really affect how you feel about yourself, and it did for years, but now I know that performance meant a great deal to a lot of people. I can't dispute the fact that it revolutionised our careers. It did so much for us, I should see that as a positive.”

Herring’s fragility courses through the band’s new record, As Long As You Are, their sixth, which grapples with self-acceptance, body image and heartbreak. It’s warmer than their previous albums, with Herring having written parts of it in the Swedish countryside. “It was the beautiful beginning of spring,” he says, “and everything was blossoming around me. I was in the comfort of the person I love, and I was like, ‘How the hell did I end up here?’”

Herring is a lively conversationalist, his eyebrows dancing in delight as he rattles off anecdotes. At one point, he jerks his body forwards and widens his eyes as he recalls breaking a toe during another especially energetic performance, on Jools Holland. He tells me he’s now in the throes of the most healthy and loving relationship of his life – and it shows.

There’s a song on the record, “Glada”, that’s all about being worthy of love. Are there times Herring has not felt deserving of it? “Of course,” he says. “I’ve pushed people away who really cared about me because I didn't know how to deal with being loved. But I've also felt I was completely deserving of love and not received it,” he says. Herring often felt isolated as a child, and this feeling has clung to him long into adulthood. “I’m now in a place where I can look back on relationships and be like, ‘What the heck was that? Why were we hurting each other?’ But before finding love again, I was giving up on it and that romantic heart I’d always believed in so deeply.”

Herring links his reluctance to accept love to his self-esteem struggles, a theme that’s confronted in the track “Plastic Beach”. “I was a chubby little kid,” he says. “I always felt fat, ugly, picked on. It meant I learned to be really tough. I had a bad mouth. By the time I was seven, nobody really messed with me.”

Herring becomes tearful when speaking about one particular lyric in the song. “Spent a lifetime in the mirror/ Picking apart, what I couldn’t change/ But I saw my mother, my father, my brother/ In my face.” After reciting it aloud, he pauses to compose himself. “That line really breaks me,” he says. “If I want to change these things about myself, but my face is made up of all the people I love, how could I ever want to change that?”

While Herring exposes his deepest vulnerabilities in Future Islands’ music, he’s not so comfortable overtly stating his political views through the band. New song “The Painter” subtly approaches race issues but another track about gun violence didn’t make it onto the record as the tone didn’t quite fit. “It’s difficult,” says Herring. “When I’m saying something really strong, I want to say it on my own so whoever has a backlash against it, it’s with me. But when I’m with the band, it's like, ‘Is it okay if I write this?’”

Outside of Future Islands, Herring raps under the moniker Hemlock Ernst. He says he’s more confident communicating his politics through hip-hop. So, what is it exactly that he wants to say? “It’s infuriating what’s happening in my country,” he says, his voice edged with rage. “The gross, disgusting hatred towards people because they’re different – it doesn’t make sense. I have issues with America at its core: the way we still don’t recognise the systematic, institutionalised racism of our country, the genocide of the Native American peoples, the enslavement of African peoples to build this nation, who are left with nothing at the end of it and are still treated like they’re not Americans. How do we speak of an American dream that doesn’t speak for all Americans?”

Donald Trump, he says, is the “personification of the white supremacist structure”, and he is angry with “fake patriots”, too.

“People fight against human rights and call themselves patriots,” says Herring. “You’re not a patriot, you’re not fighting for America, you’re fighting against everything that’s American.”

Despite Herring’s reticence to politicise Future Islands, he says fans who hold these views are not welcome at their shows. “We can’t say, ‘I’m going to straddle the line now because I don’t want to lose my audience,’” he says. “No, if that’s the audience, get them out of here. Shame them. Hopefully you can educate them, but if not, shame them into education. People need to...,” he breaks off, a shudder running through his body. “It just makes me so mad. The lack of empathy in this world is insane. And it’s just a mind-turbine, spinning, spinning and chewing up all idealism and all love. I don’t know what is happening.”

Herring catches himself, chuckles and apologises for getting so “riled up”. His restlessness is understandable – for more than one reason. Future Islands should be touring right now but, instead, Herring is flying back to Baltimore to perform one livestreamed show with the band – their only gig of 2020.

It must be weird for a group who are known for their gruelling tours, having played 150 shows a year for five years straight between 2008 and 2012. But the band suffered major “burnout” from being on the road, says Herring, especially when they went from playing to crowds of 400 to arenas of 2,000 while touring Singles. “The sets got longer, the stages got bigger,” says Herring. “All of that makes touring more physical work. Especially for me, because I was trying to figure out how to get across the stage in an interesting way.”

He smiles, thinking of Letterman. “That’s how the performative dance movements began with Future Islands. You can walk, run or dance – why not do them all?”

As Long As You Are is out on 9 October on 4AD

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments