From Wilko Johnson to The Kinks’ Dave Davies, the musicians who came back from near death

'Man, I’m supposed to have been rotting in the ground for a year'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pop adores its pretty young corpses, from Jimi Hendrix to Amy Winehouse. The flame that burns out before it can disappoint always has an allure. But, as Julien Temple’s new film The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson shows, coming back from near-death can be a weirder and more fascinating path. As other musicians including The Kinks’ Dave Davies, and Edwyn Collins, have found, facing your end then somehow surviving it can force you to confront what your life and music is for.

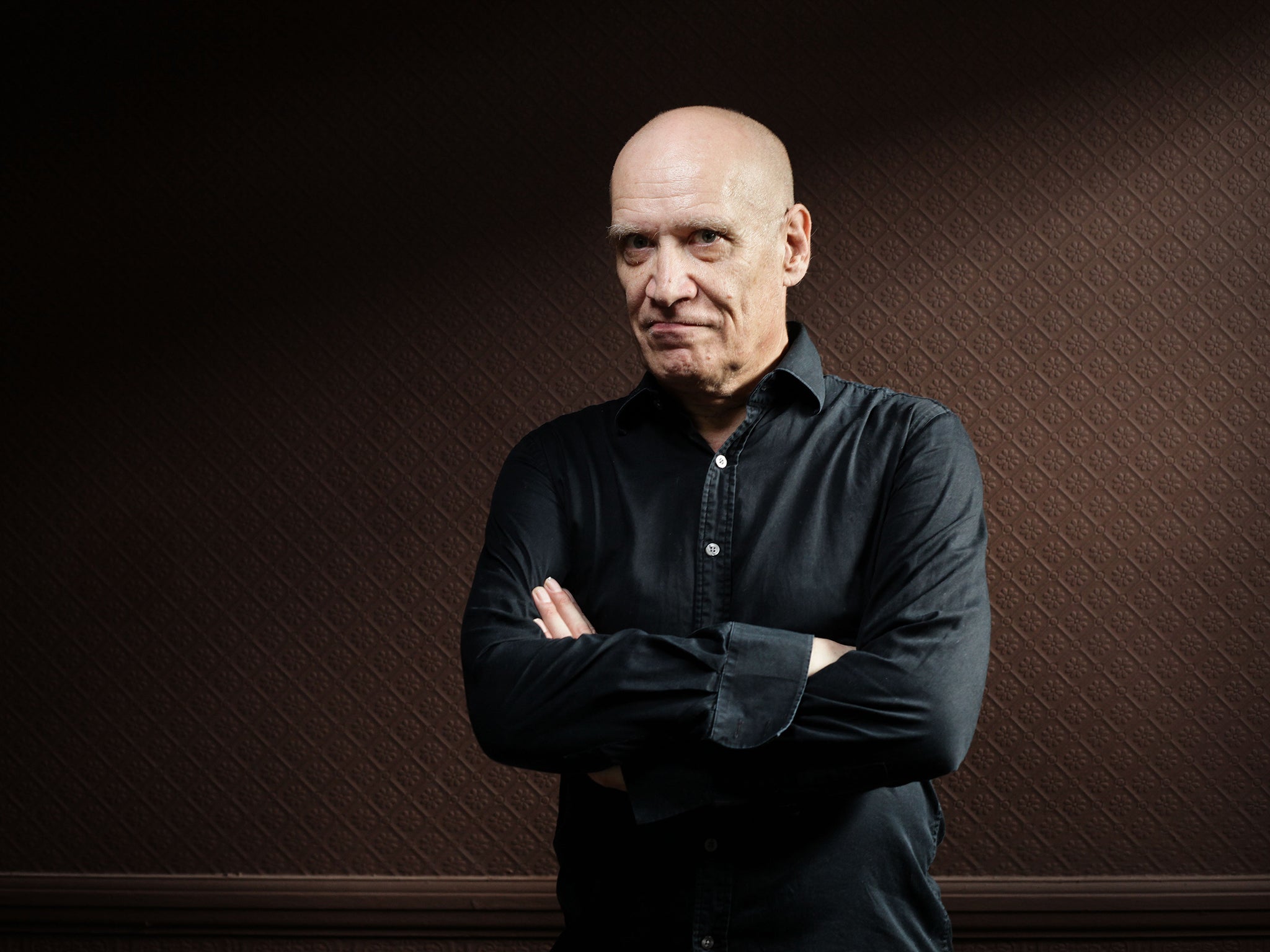

“Spring 2014,” Wilko Johnson muses at the start of Temple’s documentary. “My life is coming to an end. It’s been a strange year...” The former Dr Feelgood guitarist had been a remarkable musician and eccentrically unique person long before he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer in January 2013. But his public explanations of how this death sentence had made him shrug off his constitutional melancholy and embrace the ecstasy of being alive made him loved as he’d never been before. His farewell gigs at London’s Koko that March were among rock’n’roll’s great moments, his guitar-playing more vividly personal than ever, as love poured from a tearfully happy crowd.

But then, even more astonishingly, he was rediagnosed with a rare, just barely treatable cancer. The guitarist beat the odds again to survive an operation with an 85 per cent chance of death. Knowingly facing the day of his likely death on that operating table held no terror.

“Dealing with my illness made me pretty fatalistic,” Johnson remembers. “There was some apprehension, I suppose. The night before I went in the hospital, we were watching that film Gravity, about someone hopelessly lost, cut off from all help, and it was getting a bit much for me. I almost said, ‘look, can we watch something else?’”

The Kinks’ guitarist Dave Davies had his brush with mortality when, aged 57, he got into the lift after a radio interview in Broadcasting House on June 30 2004, and was felled by a massive stroke. “I didn’t lose consciousness,” he remembers. “I could see everybody around me. It was like they were in a movie, and I was a camera, looking through a lens. And it seemed like we’d done all the rehearsals, and now we were in the actual film. And it was layered with memories of the past, and catching glimpses of the future.” His later song “Rippin’ Up Time” was inspired by those moments.

Edwyn Collins fell even deeper into such desperate, altered states, when two major strokes sent him into a coma, aged 44, on 20 February 2005. In the 2014 documentary The Possibilities Are Endless, which shows his personality and language submerged and scattered, Collins recalls: “It’s scary stuff, what’s happening to me. I’m struggling to come to terms with who I am.” That struggle became musical when Collins decided to play again. The film shows him inspecting his studio, struggling to remember what it, and he, did. This disconnection from what previously came so easily was also felt by Johnson, who went longer than he had since his twenties without gigging, and wondered if he still could, and by Davies, who doubted he’d play live again. The Kinks man went to sleep cradling his guitar in the hospital, letting his fingers remember what he did, while he slept.

Tash Neal, the guitarist and vocalist with New York band The London Souls, was thrown even further from his work when, after being hit by a car in 2012, he woke from a coma. When he was played the album he’d just finished recording, he didn’t recognise himself on music he had no memory of making. Though still severely brain damaged, he was inspired to go on the road when he wasn’t supposed to be walking or talking, and play more fiercely than ever. “We’ve been touring for three years straight now,” he says proudly, “and that probably made me stronger. Music is healing.”

In May at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival, the resurrected Wilko played with a different, equally brilliant sort of joy than at those “farewell” gigs. “I’ve gone through weird changes of consciousness over the last couple of years,” he considers. “During that year when I was dying, it was really good for the gigs – because you just don’t care, because you’ve got no future. Just go out and play, for the sake of it. And I’ve still got that with me now. But a lot of the lessons I learned are fading away. I still can’t get used to the idea of looking more than two or three months into the future. But slowly, slowly I’m getting used to the idea that my life is not about to end. And the whole experience of that year facing death is now like a kind of dream. I think about it, and I can’t really imagine it. I am still coming back alive, if you like.”

The two albums Collins has recorded since his strokes have tended to be gentler than before. Davies feels his creativity has been liberated on his two, rapidly recorded recent albums, I Will Be Me and Rippin’ Up Time. They describe a helplessness very different to rock’s early, adolescent anguish. “It’s a desperate and weird state when you’re recovering,” he says, “so there are emotions in the songs like frustration. Anguish, loss, fear, being alone. Sometimes you just want to scream. I feel it perks the music up. Also, once you get over the shock of an experience like that, you can’t take things too personally. The fear of criticism went away. I’m experimenting a lot more than I would have, being less calculated and methodical.”

Walking out to play again, at New York’s City Winery, on May 28, 2013, was the final step in Davies’s recovery. “It’s funny,” he remembers, “that first night, I was so terrified, and I came on stage, and it took me 10 minutes to get into the groove of things – the lights, and the smells, the audience brought me back. You have to keep reminding yourself what it is you do. Smells are really important, when you’re ill, to that sort of recovery, and your memories.”

The way he faced his fear, standing in the wings, let Davies carry on. “I finally thought: ‘Oh fuck it, how bad can it be?’ And that released me, in a way, from consequences. I think the best art is without consequence – instead of, ‘I’d better do that because I’ll get that much money’, which is so contrived, and becomes anti-art. It was almost feeling, after that first show, that maybe what happens now doesn’t matter. I’ve got that far, so maybe that’s all I needed, to push me in the right direction. And whether I played again or not didn’t really matter.”

Johnson is still adjusting to the novelty of being alive for the foreseeable future. “I’m just going along doing whatever. I think: ‘What is there now?’ And the mystery’s not immediately in front of my face any more, like some door slamming, it goes on and on. I don’t know what to do. I also find my old personality is returning, and unfortunately I’m a bit of a miserable so-and-so. I think: ‘Oh come on, man, someone’s given me this indefinite future, it’s free.’ So it’s annoying to find myself moping. I could contrive to feel miserable in the Garden of Eden. Whereas, the Valley of the Shadow of Death, it’s not all downside!”

As The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson makes clear, he has been on one of rock’n’roll’s very strangest trips. “We have remarked many times, my chums and I, that if you wrote the story of that year down in a book, it would be condemned as an improbable fiction. Sometimes I just have to laugh when I look around me and think: ‘Man, I’m supposed to have been rotting in the ground for a year. And I could get up right now, and walk to the corner shop and get some milk.’”

‘The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson’ is out now (ecstasy-ofwilkojohnson.com). ‘Here Come The Girls’ by The London Souls is out now. Dave Davies plays Islington Assembly Hall, London on 18 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments