From Peter Grant to Brian Epstein: The mavericks of music management

They are often marginalised or maligned, but some impresarios have had a huge influence on the course of rock history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Watching Svengali, the tale of a postman from South Wales who dreams of following in the footsteps of the great rock impresarios, one can’t help but reflect on Britain’s long-standing tradition of maverick music managers. Directed by John Hardwick, the comedy evolved out of the cult internet series based on Jonny Owen’s experiences with 1990s indie band The Pocket Devils, whose manager, the hapless Paul “Dixie” Dixon, fancied himself as the new Malcolm McLaren. Needless to say, in Svengali the Premature Congratulations don’t turn out to be the punk game-changers the Sex Pistols were in 1976.

Owen’s character is reminiscent of Gareth Evans, the Manchester outsider whose chutzpah proved crucial to the emergence of the Stone Roses, even if his eagerness to sign to Zomba imprint Silvertone in 1988 tied the group to a one-sided contract they spent years trying to extricate themselves from. This setback contributed to their mystique and enduring appeal. Evans was prepared to go the extra mile for the Stone Roses, but his inexperience let him down.

Equal parts nanny, cheerleader, confidant, enabler, prompter, creative sounding board, businessman and lawyer, a music manager’s job is manifold and never done.

“A good manager is almost a frustrated artist. He can’t be on stage so he tries to live through their success,” says the entrepreneur Chris Wright, who recently published his autobiography, One Way Or Another: My Life in Music, Sport and Entertainment. Wright managed Ten Years After to international success in the late 1960s, re-invigorated the career of Procol Harum in the 1970s, and co-founded Chrysalis Records. “Artists need direction. The manager has to be able to stand up to the artist and say what he thinks, not just be a yes man. Peter Grant was a brilliant manager. He learned the hard way, he fought for his artists. The success of Led Zeppelin was down to a great relationship between him and Jimmy Page. They respected each other.”

The first British pop manager, the flamboyant Larry Parnes was the Simon Cowell of his day, giving his protégés fanciful stage names such as Tommy Steele, Marty Wilde and Billy Fury, and grooming them to make the transition from teen idol to all-round entertainer in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Nicknamed “Parnes, Shillings and Pence”, he put his clients on a weekly wage, and was arguably the first man to turn down the Beatles, who, as the Silver Beetles, backed his client Johnny Gentle on a Scotland tour in 1960.

Brian Epstein, who took on the Fab Four in January 1962, had an enormous influence on their career. He smartened them up, replacing leather jackets and jeans with suits and ties, and secured a deal with Parlophone after most UK companies turned them down. Yet the “fifth Beatle” made some awful business decisions, particularly about merchandising and publishing. Following his death in August 1967, the group set up Apple but struggled to keep a handle on the business. When John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr hired the notorious New Yorker Allen Klein to manage their affairs, Paul McCartney opposed the move, precipitating the break-up of the biggest band in pop music history.

Klein had previous, having bought Andrew Loog Oldham’s share in the Rolling Stones’ management in 1966. A PR genius, Oldham masterminded their emergence as the raucous, outrageous antithesis to the Beatles, and pushed Mick Jagger and Keith Richards to write their own material. Yet, he proved unable to cope with the band’s drug busts of 1967 and his own drug use. Immediate, the label he set up in 1965, enjoyed success with the Small Faces and Humble Pie, but ceased operating in 1970.

The partnership of Kit Lambert, the public school-educated son of composer Constant Lambert, and the streetwise Chris Stamp, the brother of actor Terence Stamp, played a crucial role in the rise of The Who and their transformation from the stuttering mods of “My Generation’’ to the originators of the rock-opera genre with Tommy. They encouraged the creative flights of fancy of guitarist Pete Townshend, but fell for the rock’n’roll lifestyle, leading to a parting of the ways in the mid-1970s. The movers and shakers also signed Jimi Hendrix to their Track label.

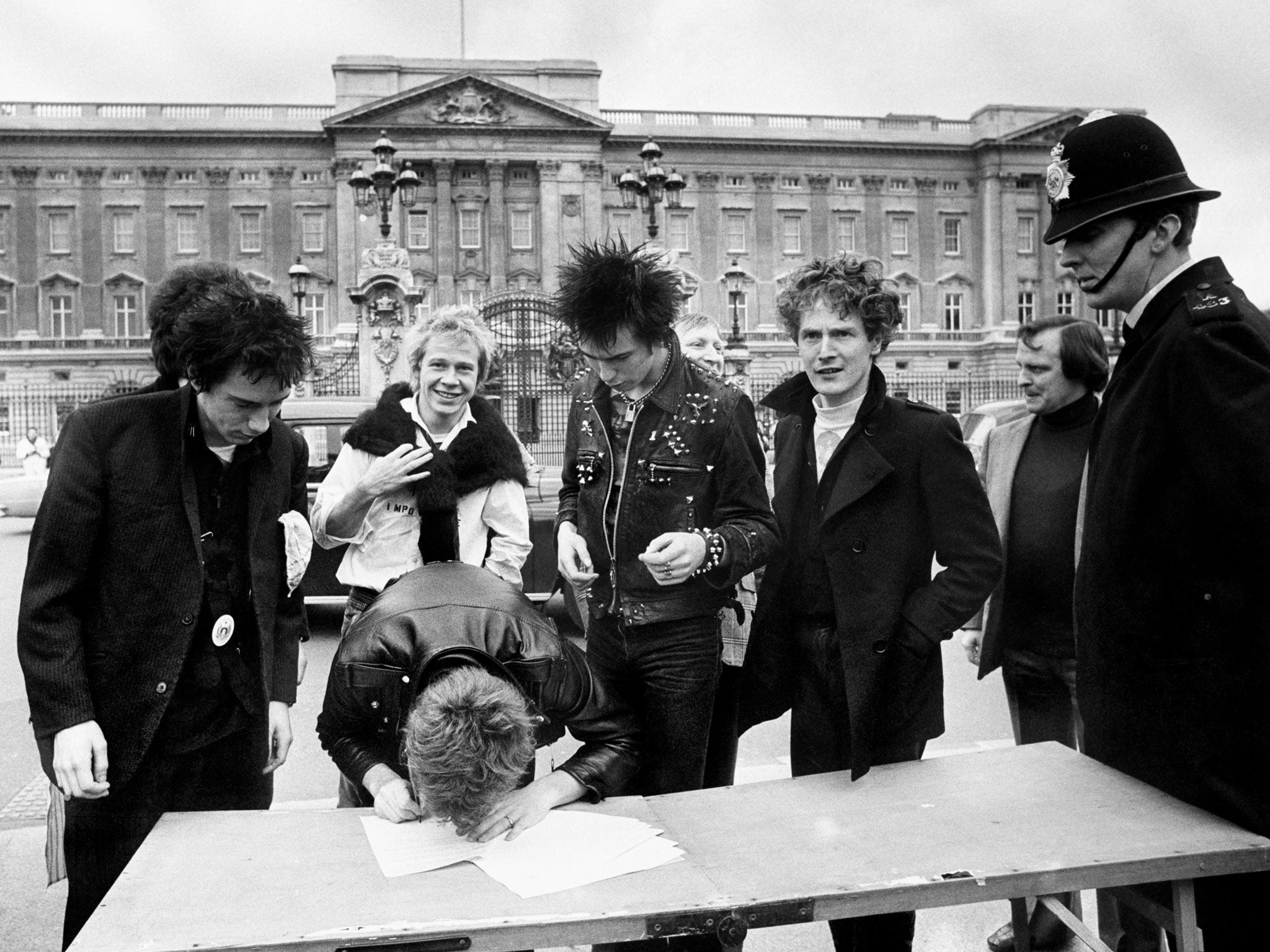

A maverick par excellence, McLaren tried to reinvent the New York Dolls as “Better Red Than Dead” communists but found his métier orchestrating the furore around the Sex Pistols, making cash from chaos with successive record deals with EMI, A&M and Virgin. However, he failed to put out the fires that led to the sacking of bassist Glen Matlock, whose replacement, Sid Vicious, died on his watch, a no-no in Wright’s eyes: “If an artist dies of a drug overdose, the manager is at fault to some extent. Often, the manager’s job is to stop a band breaking up.” McLaren’s next shock tactics involved Bow Wow Wow, fronted by the under-age vocalist Annabella Lwin, before his ego led him to solo success with Duck Rock in 1983.

Borrowing McLaren’s punk blueprint, McGee managed the Jesus and Mary Chain and orchestrated the press coverage that put the Glasgow group on the front pages of the British music press in the mid-1980s. He subsequently concentrated on Creation, the label that gave us Oasis and My Bloody Valentine, and has a cameo in Svengali that blends reality and fiction.

Wright thinks the larger-than-life managers, the fifth or sixth member of the group, are no longer the currency. “Jim Beach, who looks after Queen, came to management from being a lawyer. Steve Dagger is very close to Spandau Ballet, he is one of the last mavericks. Artists get the managers they deserve and managers get the artists they deserve.”

‘Svengali’ is out on 21 March and available on DVD from 7 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments