From one African legend to another

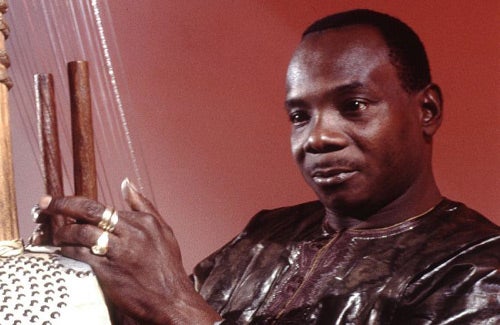

The Malian kora master Toumani Diabaté won a Grammy for his collaboration with Ali Farka Touré. In Spain for a rare solo show, he tells Tim Cumming about his new CD, dedicated to Touré and others, and explains why he never plays a piece the same way twice

The mayor of Seville has arrived with his retinue of grey-suited retainers, passing through the Courtyard of the Crossing into the Sala Grande, the great tapestry room of the Alcazar Palace, which is rapidly filling with invited guests, every scrape of chair and throat echoing in the Sala Grande's 500-year-old acoustics. World Circuit record label's engineer Jerry Boys is adjusting one of the four microphones directed around different parts of the kora that is set upon a stand on the makeshift stage.

The kora is a classical West African instrument dating back to the 14th century. We are here to see the world's foremost kora player, Toumani Diabaté, perform a rare solo recital. Diabaté can trace his griot lineage that far too, the instrument handed down from father to son in an uninterrupted line. It is still made the same way – calabash, cowskin, leather rings for tuning, and fishing wire for the chorus of 21 strings circling the wooden bridge.

Among his classic albums over the last two decades are collaborations with Taj Mahal, the flamenco group Ketama, the bassist Danny Thompson, and his duets with the late Ali Farka Touré, recorded in the Mandé Hotel in Bamako in 2005. Tonight, though, he is absolutely alone. The concert is a one-off event in advance of his new album, The Mandé Variations, and is being broadcast live on Spanish radio, an hour-long recital of four songs and an encore, compelling even the most persistent throat scraper into awed silence.

The invention and intelligence of his music is woven of such fine and fluid material it's as if you're caught in its stream. The play of his fingers begins to take on an almost supernatural, djinn-like intensity of purpose as he moves deeper into his themes, spinning architectural abstractions over bass melodies and rhythmic grooves. Like the works of Bach, it's a music that leaves you cleansed.

Diabaté's international career dates to his first British gig at a small club in Bristol in 1986 when he was 21. Later that year, while staying in London with the writer and broadcaster Lucy Duran, he cut his first album, Kaira. It established the kora as a compelling solo instrument, and Diabaté as one of its premier practitioners.

Twenty years on, The Mandé Variations revisits the repertoire for unaccompanied kora with a performance that surpasses anything he has recorded previously for sheer scale of ambition and technical achievement. Among the eight extended pieces on the album, he pays tribute to mentors and master musicians who have passed on – his spiritual guide Ismael Drame, fellow kora player Kaunding Cissoko, and the late, great Farka Touré.

"The Mandé Variations shows the way the kora should be played," he says, talking quietly but with absolute certainty. "I take the kora to another level with this album, the way Ravi Shankar took the sitar to another level."

We're sat in his top-floor hotel-suite a short walk from the Alcazar, a couple of hours after his late arrival via Paris and Madrid from Bamako. His kora is beside him in its bulbous case, the same kora given to him by his father Sidiki Diabaté 40 years before. His second instrument, a modern machine-headed kora (without leather tuning rings) is tuned to his own "Egyptian" scale and used on the album's more abstract, modernist improvisations.

It was his father who pioneered the style of simultaneously playing bass accompaniment and solo that Diabaté has made so much his own. "I keep it moving. I develop styles to give it more groove. My father didn't play it like this. My grandfather didn't play it the way my father did, and my son is playing in a different way from me." He smiles. "He's 15, and he's a great, great, great kora player." But tradition is everything. "The traditional kora has a history, and you need to understand that history because it is unique in the world. You can't find it anywhere else."

Diabaté writes nothing down. The music he carries with him on to the stage is between his heart and fingertips. "I didn't learn the kora with anyone, it was a present from God. The inspiration comes to me straight away when I play – I can't explain what happens, it's like fighting something. Making an audience happy is a fight, because you need to be concentrated, to do something to catch the people and touch them in their heart, you need the people to say afterwards, 'thank you'. You need that."

The album's title refers in part to the spirit of the Hotel Mandé sessions with Farka Touré in 2005. "Another spirit for this album is to get into the classical way," he says. "People say that classical music is in the guitar or violin or flute but never the kora. Why not? Some people say African music is only dance music, it's only ambience. But its not for ambience, it's the roots of music, and people need to see the different levels of it. We have music for meditation, we have spiritual music, we have music for dance, for ceremony, for tradition, for weddings, funeral music."

The spiritual aspect is uppermost in his mind today. Several times he comes back to the theme of music as spiritual guide. "The world today is very hard everywhere. People dying in bad ways, fighting, democracy, money, oil, terrorism. Today we forget that we've been created to be spiritual, we forget that we follow the money, something we created, and we forget the spirituality."

The Mandé Variations flickers with highlights from beginning to end, but his improvisation for Farka Touré must rank as one of its most haunting performances – and one that he played for the first time as he recorded it.

"I can't explain how much I was happy with Ali," he says of his friend and mentor. "I have this in my heart. I just take the kora, tune it, and play it. Jerry Boys records it and then I listen to it. It is like a communication with someone or some spirit. I come in with a spirit in mind. Today I think of him like this. That's why I play this song in just one take. I can never play exactly like this ever again."

When the two of them recorded In the Heart of the Moon, it was over three two-hour sessions, and The Mandé Variations follows a similar work ethic. "I recorded all of this in two hours," he says, smiling. "The whole album. I did in two days, one hour one day, one hour the other. This music I play, it comes from the heart, connected through the strings. I can't explain what I think and feel when I'm playing. When I play songs I become more happy, it's like talking. It could be fast, or slow, it could be in the middle." He stops talking for a moment. "But the groove is here in this hand."

'The Mandé Variations' is released on 25 February by World Circuit

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks