Frank Sinatra 20 years on: How 'Ol' Blue Eyes' fell out of fashion and why his records deserve better

'Chairman of the Board' too often overlooked due to ubiquity of most famous songs, mob connections and fraught personal life but best albums reveal a master at work

Frank Sinatra, one of the greatest American voices of the 20th century, died on 14 May 1998 – exactly 20 years ago today.

One of the biggest stars to emerge in the post-war years, Sinatra was beloved by millions for albums like Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! (1956), Come Fly with Me (1958) and Nice ‘n’ Easy (1960).

He was also a gifted actor and enjoyed the kind of celebrity that has since become commonplace (but was then a new phenomenon) as part of the “Rat Pack”, photographed wherever he went with pals Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr and Peter Lawford, their lavish lifestyle widely scrutinised and envied.

A prince of American prosperity, Sinatra’s alpha tough guy persona embodied his country’s consumer confidence in the 1950s, his booming delivery speaking to modern aspirations about how to live and depicting a man’s world of custom suits, cocktails and foreign travel, all tantalisingly within reach. The extent of his influence during his heyday cannot be overstated.

But lately the “Chairman of the Board” seems to have fallen badly out of fashion.

In part, this can be attributed to the inevitable scorn that comes as a by-product of mass popularity. Over-familiarity has also bred contempt for Sinatra’s big band-heavy back catalogue. “New York, New York” has been pummelled into cliche and “Come Fly with Me” is hard to dissociate from travel agency advertising.

It is also no doubt due to the fact that the kind of noirish cool “Ol’ Blue Eyes” once stood for has since been entirely eclipsed by a succession of pop cultural movements, from garage rock to psychedelia, punk, new wave and hip-hop.

Sid Vicious’s solo cover of “My Way” from 1978 was a deliberate trashing of his legacy, the Sex Pistol insolently thumbing his nose at a man who had, to the punks, become a stale conservative icon long overdue for a debagging. The fact that the end result was unlistenable was part of the point.

Perhaps the biggest reasons though are more personal. What first springs to mind for many these days are Frank Sinatra’s mob connections, defection from the Democratic Party and the array of anecdotes dwelling on his undoubted mean streak.

Hailing from working class Italian-American stock in Hoboken, New Jersey, Sinatra’s godfather was Genovese crime family boss Willie Moretti. He was personal friends with crooked Las Vegas casino kingpin Sam Giancana, mobsters Joseph Fischietti and Mickey Cohen and holidayed in Havana with Lucky Luciano.

Stand-up comic Jackie Mason recalls being shot at in his Vegas hotel room in retaliation for telling jokes at Sinatra’s expense.

The crooner always maintained that ”Any report that I fraternised with goons or racketeers is a vicious lie” but the suspicions were such that the FBI observed him for four decades. John F Kennedy, whom Sinatra had been a vocal supporter of, was forced to distance himself from the star in 1962 as his brother Bobby, then Attorney General, turned the spotlight on organised crime.

Sinatra was infuriated by this snub and in later life grew increasingly right-wing, throwing his considerable political weight behind Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election and later going to bat for Ronald Reagan.

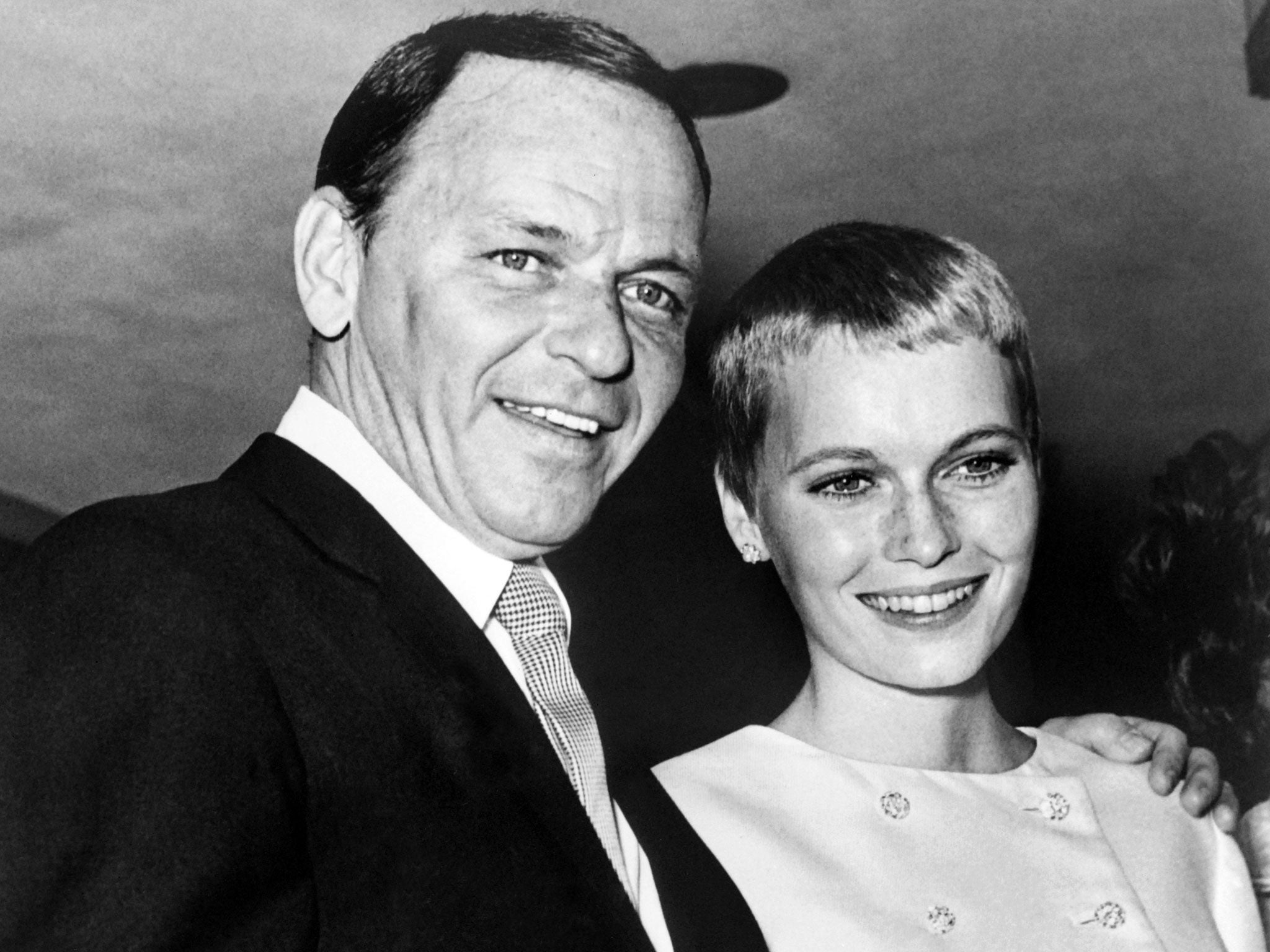

His treatment of women also left plenty to be desired. A career philanderer, Sinatra became known for the seething jealousy and many fights he endured with his second wife Ava Gardner. He was particularly controlling when it came to his third, Mia Farrow, angrily serving her with divorce papers on the set of Roman Polanski’s film Rosemary’s Baby in 1968 when she refused to quit the project at his say-so.

None of this is reflects well on him but then being nice was never a prerequisite for great artistry and arguably Sinatra’s contradictions fed into his best work.

On both In The Wee Small Hours of the Morning (1955) and Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely (1958), arranged by Nelson Riddle, the star essays a bruised masculinity and a vulnerability entirely at odds with the public image cultivated in his breezier film outings like Ocean’s 11 (1960) and Tony Rome (1967).

These concept records are exercises in melancholy mood building, made up of torch songs written by such luminaries as Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Cole Porter and Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

On songs like “Glad to be Unhappy”, “Deep in a Dream” and “When Your Lover Has Gone”, Sinatra brilliantly embodies the brooding sadness and anger of urban male isolation. These albums conjure miniature movies in the mind. Listening to them is like watching Scottie Ferguson from Vertigo (1958) or Mad Men’s Don Draper smoking alone in the dark, contemplating their wounded egos and existential dismay.

Nowhere is this truer than on “One More for My Baby (and One More for the Road)”. A morose ballad, Sinatra sings his woes to an indifferent bartender cleaning up after last orders when everyone else has gone home. The delivery is perfectly paced, the atmosphere exact. A self-pitying scene worthy of Edward Hopper. Only fellow Jersey Boy Bruce Springsteen, in “Highway Patrolman” mode, comes close to creating a whole world in a four-minute narrative song.

Sinatra would channel a version of this persona into his performance as a morphine-addicted jazz musician in Otto Preminger’s film The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). This guise always represented a more fitting use of his talents than belting out swing standards for the boys snapping their fingers in business class.

Tom Waits appreciated these albums and parodied In The Wee Small Hours’ cover art – a painting of Sinatra emerging dejectedly from an alleyway into a deserted lamp-lit street – on the cover of The Heart of Saturday Night (1974).

More recently, Bob Dylan made a compelling case for the re-evaluation of the Sinatra songbook with the release of Shadows in the Night (2015), a covers album shining new light on the sort of reflective standards Frank once made a speciality of.

Frank Sinatra may not have been a great guy all the time but he took risks artistically and he did have his moments.

When heavy metal star Alice Cooper invited a small boy to join in with a celebrity baseball tournament in Los Angeles in 1977, Sinatra summoned him and explained that the kid was the son of a friend and that he therefore owed “Coop” a favour. To pay him back, he sang his song “You and Me” at the Hollywood Bowl and posed for pictures to send to Cooper’s mother.

No saint, Sinatra deserves to be respected for one of the most extraordinary bodies of work in the history of American popular music.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks