Foals’ Yannis Philippakis: ‘We were broke, we were having fun, you could smoke 40 cigarettes and not have a cough the next day’

Roisin O'Connor shares a pint with the frontman as he talks about escaping the pandemic through nostalgia, swapping dysfunctional angst for jubilant optimism, and why Partygate does matter

Interviews with Foals often read like a local’s guide to south London watering holes. This is mostly thanks to frontman Yannis Philippakis, who has lived in the area since the rock band’s early, hedonistic days in a Peckham squat dubbed “Squallyoaks”. Pubs are where the 36-year-old seems most at home, and boy, did he miss them during lockdown. He’s even written a song about it.

“I was starting to go out of my mind, with the pubs not being open,” he tells me, nursing the first of a few lunchtime pints on a sun-dappled street outside a tavern in Camberwell. He’s dressed casually in a loose shirt and jeans, sporting his usual forest-thick beard and shock of jet-black hair. We’re speaking the day before the band – whittled down from a five-piece to a trio over the past few years – head out on the road for a string of pre-Glastonbury shows around Europe. Philippakis is joyous at the prospect of live music and a new album, Life is Yours, which is out next week. The beginning of lockdown was “fairly wholesome”, he says. “I was a healthier version of myself than on tour – I enjoyed being domestic.” Then, when it became clear the pandemic wasn’t going anywhere soon, he grew restless, and the band started to write.

“You write yourself out of the situation,” he says. Working in a sparse room in London in the depths of a particularly bleak winter, he found himself thinking back to the band’s inception at Oxford University in 2005, then moving with drummer Jack Bevan, guitarist Jimmy Smith, and former members Walter Gervers (bass) and Edwin Congreave (keys) to a shared house in Brighton. It was there that they developed their reputation for smart, agitated indie-rock, with singles such as “Cassius” from their 2008 debut Antidotes setting Philippakis’s anxious yelp against a danceable soundtrack. “It’s a transportive mechanism,” he says of songwriting. “[It helped me pretend] I’m not 36 and living in the middle of a pandemic, I’m 25 and…” He trails off, lost in memories of those notorious house party gigs, reflecting on lyrics about “Brighton Rock!” and “blue tongues in summer rain”. I tell him I’m surprised to hear him talk like this, mostly because in early band interviews, 25-year-old Yannis sounded like a bundle of neuroses compared to the man sitting opposite me now.

“Around [2010 album] Total Life Forever, I was f***ing miserable,” he says. “In the early stages of the band I was just ridden with angst and anger.” Promoting that second album, he described himself in interviews as “dysfunctional” when it came to relationships and admitted he had trouble getting close to people. “We were living in this house together, we were broke, we were having fun, you could smoke 40 cigarettes and not have a cough the next day… but we probably had an insecurity about the music we were writing,” he says. “But I look back now and it was awesome. I’m glad we did it like that.” New songs such as single “2001”, a squelchy, jangly funk-pop jam where Philippakis cha-cha-slides over shimmering guitar riffs, are attempts to “rewrite the past” a bit. “It adds this veneer, a layer of positivity that removes the hangover of the big night.” Others, like “Flutter” – about “domestic abandonment without explanation” – address it in a more impressionistic manner, against a backdrop of Tony Allen-indebted jazz grooves. Philippakis was actually working on a collaborative project with Allen before the Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer’s death in 2020; he plans on completing it in the future.

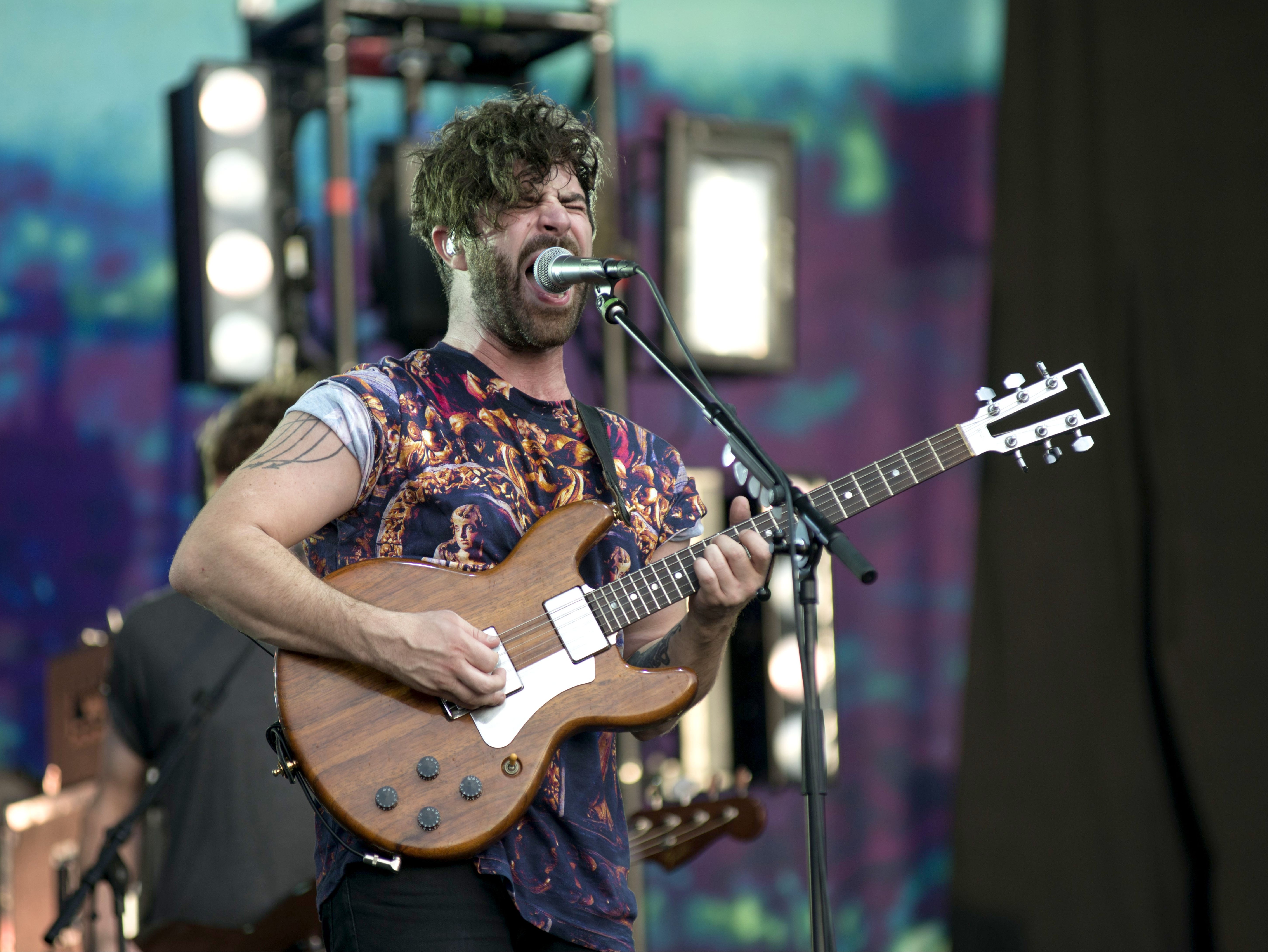

Life is Yours is celebratory, darting between an optimistic present and a nostalgic past. It’s arguably the first of Foals’ seven albums where Philippakis isn’t preoccupied by his concerns for the future. The son of a South African academic mother and a Greek architect father, who divorced when he was five, he’s prone to deep ruminations on technology, social behaviours and the nature of human beings. This is a man who, in 2017, chose to spend several weeks post-tour in the fortress-like monasteries of Mount Athos, in north-eastern Greece. Yet there’s also a bristling physicality about him, simmering behind the brooding facial features and stocky build, which translates into a volcanic stage presence at the band’s live shows, and to their music’s propulsive, muscular rhythms. On 2019’s twin albums, Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost Part 1 and 2, the band tapped into the tumult of a post-Brexit Britain and the ever-increasing threat of the climate crisis. The first part earned the band their third Mercury Prize nomination; the second was the last record featuring Congreave, who left amicably to pursue a postgraduate degree in economics from Cambridge University, with the aim of tackling the “imminent climate catastrophe”.

“His departure did change things,” Philippakis says of Congreave, pausing to glance wistfully at the next table, where a man is chain-smoking his way through a pack of Marlboro Lights (his days of 40 cigarettes a night are long gone). “We had to recalibrate, especially after doing the double album which was so broad, because [otherwise] it was gonna become some prog parody. There was definitely an idea that we reached the end of a road.” Foals have never worked with the same producer twice (with the exception of Brett Shaw on both parts of ENSWBL), and for Life is Yours they enlisted three: AK Paul (Jessie Ware, Sam Smith), John Hill (Cage the Elephant, Shakira) and Dan Carey (Bloc Party, Fontaines DC).

“We almost always do the opposite of the album before,” Philippakis says. “It doesn’t surprise me that this is the most concise, the most light, the most direct.” The record makes him feel good in a way their other records haven’t: “We didn’t want to write songs that would add to people’s emotional burden.” Its buoyant energy – all bright ripples of electric guitar, taut percussion and shuffling Afrobeat rhythms – is nothing like the moroseness that permeated the previous two records, which now feels disturbingly prescient. “In some ways the last record was tapping into an anxiety about catastrophes, and then we had one,” he says with a shrug. Yet the songwriting on Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost steered clear of anything too literal: “It’s always gonna be slightly abstract, more poetically mangled.”

The people in power have made a mockery of the rules they made

The band were wary that the new album’s title could be construed as glib. What it does, though, is speak to a generation sick of having their lives put on hold or threatened by the selfishness of the ones who came before. The ones who, having made so many sacrifices during lockdown, came out of it to learn the rulemakers had been breaking the rules the whole time. “I find it bewildering,” he says. “The people in power made a mockery of the rules they made. And people do care [contrary to what Boris Johnson claims]. It’s actually disgusting.” Philippakis, who was born in Greece, speaks the language fluently and still visits. He contrasts the “deep but out in the open” problems of his birthplace with the “disappointing and hypocritical” idea of sportsmanship and fair play in British politics.

He managed to make a trip out to Karpathos, where his dad still lives, during the pandemic, and has started to delve deeper into his love of Greek folk music. His interest in visiting the country developed around the same time as his relationship with his dad – who makes Greek folk instruments himself – improved. “There’s some music there that I absolutely love, especially from the island my dad’s from, but I wonder how it’d land here,” he says. “Or do I do it for the Greeks?” I tell him he should do Eurovision, prompting him to recall a recent “weird email” from someone in Greece that was actually related to the annual song contest. He grins, seemingly envisioning himself among the sequins, glitter and general insanity of that world. “Can you imagine?”

‘Life is Yours’ is out on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks