Fleetwood Mac: ‘We’ll burn in hell if we don’t play Glastonbury one day’

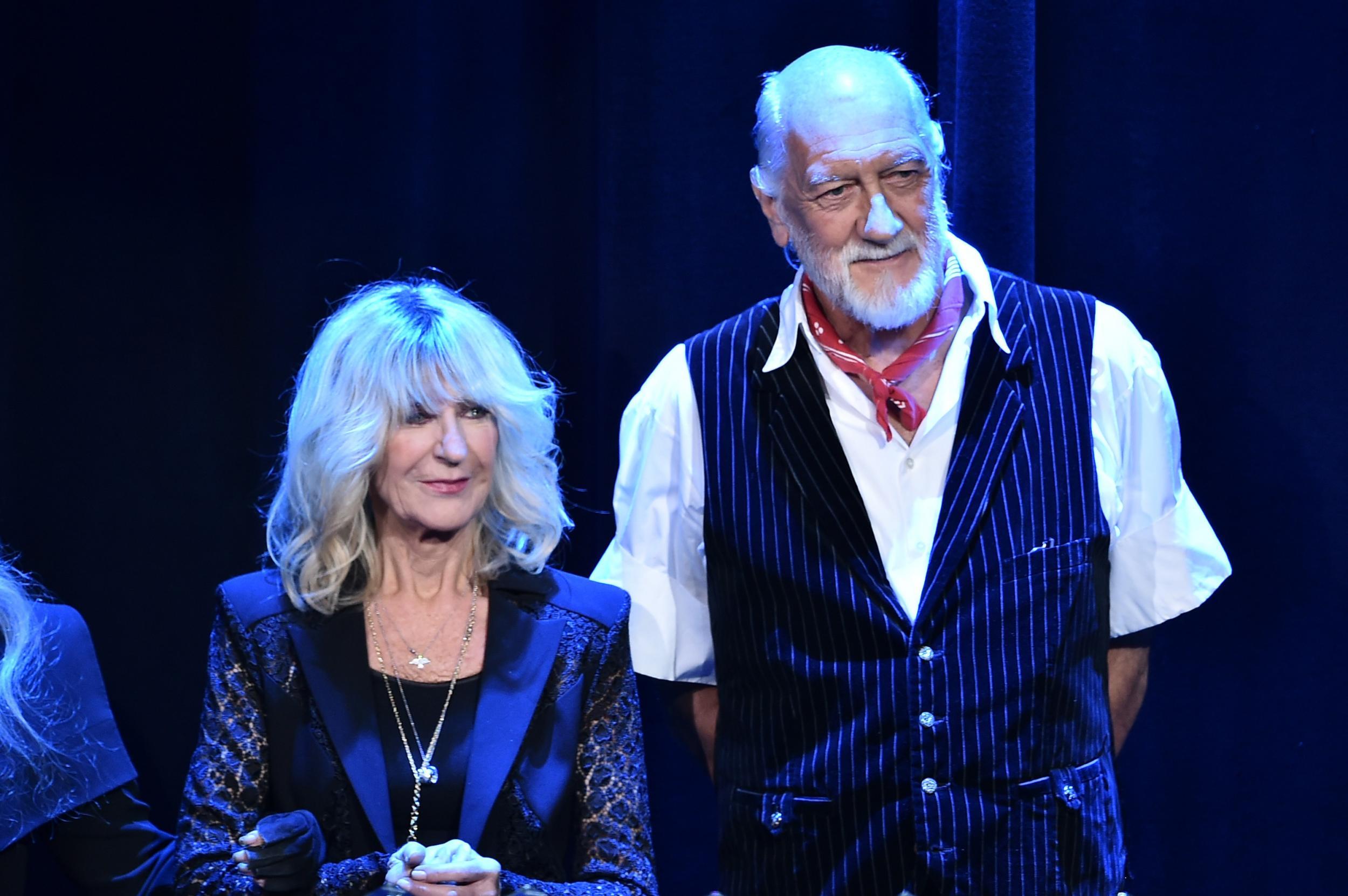

Cocaine, fights, love affairs and break-ups. Mick Fleetwood and Christine McVie speak to Chris Harvey about the success, the hardship and the torment of the band as they prepare to play Wembley in June

This strange, funny band is complicated,” says Mick Fleetwood. “It’s all about people, it’s not horrific.” I’m talking to the man who has been the only member of Fleetwood Mac to appear in every line-up of the band since they were formed. When they step out on stage at Wembley Stadium in June, that will be coming up to 52 years ago.

We’ve been chatting about the period when Fleetwood Mac moved from stars to superstars with the release of Rumours in 1977. It was during the era of Seventies rock excess, when band mythologies are wreathed in tales of groupies, sexual exploitation, drug addiction and death.

Fleetwood Mac were no strangers to drugs: LSD had cost the group its original leader, Peter Green, at the end of the Sixties, and cocaine was an integral part of the band’s Seventies. Fleetwood wrote in his autobiography that Rumours was written with “white powder peeling off the wall in every room of the studio”.

“I think we were damned lucky that our music never went down the drain because we went down the drain,” the 71-year-old drummer says now, “and I think in truth there are moments where you could have said we got pretty close, you know.

“Cocaine was everywhere, people who worked in banks [used it]. Personally, I had a run on that lifestyle, but fortunately, I didn’t get into any other type of drug that would have been more damaging – I don’t even know why, but I’m very thankful. Brandy and cocaine and beer,” he says, naming his poisons, as he describes the 20 years of “high-powered lunacy” that he put his body through. “That lifestyle became something that had to come to an end… hopefully, you come out of it with your trousers still on, and not taken out in a plastic bag.”

There’s a real warmth and self-deprecating chattiness to Fleetwood. He notes that “a lot of the moments of creativity” for the band “were intertwined with sometimes extreme lifestyle choices”. But that reference to Fleetwood Mac being complicated, not horrific was in response to a question about whether the fact that there were women in the band – Christine McVie joined in 1970, Stevie Nicks in 1975 – meant that they avoided the sort of behaviour that people associate with the likes of Led Zeppelin and Vanilla Fudge at that time. “Absolutely no doubt about it and thank god,” he says.

“All of us… anyone that’s been in Fleetwood Mac as far as I’ve been aware has been seemingly pretty well brought up by their parents – not goody two-shoes, god knows we weren’t, but there was a level of civility that the lads in the band were aware of; what is over the brink of decency. We all hear and know some of the things written about other bands, where you go, ‘oh my god’.

“Often the chemicals in young men and women are busting loose, that’s part of growing up, and when you’re growing up in a rock’n’roll band, guess what? You’re tending to jump down the local discotheque for a night out, but a lot of that was hopefully tempered,” he adds.

Christine McVie confirms his take on it: “Fleetwood Mac were a rude bunch, they had dirty minds, they still do, but I used to laugh because I thought they were hysterical. I kind of became one of the guys, which I think I still am to this day, but I was always treated with great respect.”

When the band set out in 1967, of course, there were just guys, although they didn’t yet include John McVie. The Mac part of the band’s name was founding member Green’s attempt to convince McVie to leave his steady gig playing bass for the Bluesbreakers. He eventually did, with a bit of persuading. It was a wise move. The band experienced significant chart success almost from the beginning of their career, with an authentic blues sound built on Green’s virutoso lead guitar and the stellar rhythm section of McVie and Fleetwood, who to this day says he doesn’t “know” the songs, but plays them instinctively (“the power of those two,” says Christine McVie, “you can’t ever know what that feels like until you’re standing on the stage with them”).

They had a No 1 single with “Albatross” in 1968, followed by two songs, “Man of the World” and “Oh Well”, that both reached No 2 in the UK, plus three top 10 albums.

Meanwhile, the young Christine Perfect, later to become McVie, had a top 20 hit with her band Chicken Shack and a brief solo career, which produced songs such as “Close to Me”, which still sounds amazing, although McVie tells me she went back and listened to it recently and “hated it... I was not a very confident writer and that is probably one of my least favourite songs on the planet.” (Even geniuses can be wrong.)

She remembers when she and a fellow Chicken Shack band member used to trail around and watch Fleetwood Mac when they had a night off, and recalls the first time she met Fleetwood, who “had a perm, which looked awful… he was intimidating in the beginning because of his height [he’s 6ft 4in]. I was very shy of him for years.”

She married John McVie in 1968, and, according to Fleetwood, “basically retired into being his wife” in 1969 after realising that if they were in different bands they would never see each other. She had played keyboards on their 1968 album Mr Wonderful, and did so again on 1970’s Kiln House. It was the band’s first album after the departure of Green, whose use of LSD had altered his mental state in so extreme a way that it could no longer be reconciled with the rest of the band. Fleetwood told McVie, “Chris, we need you” – she joined three days before the band left for America “and then we never looked back”.

For her part, McVie says: “I didn’t want to go to America – I’m a real Anglophile, I adore England – but the rest of the band promised me, we’ll go for three months, because we had no career over there, nobody wanted to book us, and then we’ll come back… 28 years later, I got to move back to England again.”

Cocaine was everywhere. I had a run on that lifestyle, but I didn’t get into any other type of drug that would have been more damaging

McVie spent years restoring a manor house in Kent, enjoying life with her dogs, until she began to miss the band. Fleetwood has been in Maui, Hawaii, for 17 years, and lives there with his girlfriend of seven years, Chelsea Hill – “we’re joined at the hip”.

The band has been playing early tracks such as “Black Magic Woman” (later recorded by Santana) and “Oh Well” on the huge tour of which the London dates form a part, but Fleetwood says they may be digging up more of the really early stuff specially for the Wembley gigs. The return of McVie to the ranks of the band after 16 years in 2014 was “like something falling out of the sky”, he says. The band will be performing without one key member, though. Lindsey Buckingham was fired in 2018, to be replaced by Neil Finn of Crowded House and Tom Petty guitarist Mike Campbell (who also wrote the music for Don Henley’s “Boys of Summer”). The roots of Buckingham’s departure run deep.

What is now considered the classic line-up – Fleetwood, John and Christine McVie, Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham – took shape after the revolving door of guitarists leaving the band in the early Seventies left a gap that Fleetwood tried to fill with the man he’d heard playing on a Sound City studio tape of the Buckingham Nicks album (released in 1973). The duo were a couple, though, and so inseparable that Buckingham told Fleetwood that they only came as a package deal (“Stevie’s never forgiven me,” Fleetwood says). The band’s sound evolved with its new triumvirate of songwriters. Blues remained a backdrop, but Christine McVie’s classical roots, which can be clearly heard on “Songbird”, combined with Nicks’s folk-country influences and Buckingham’s innovative guitar structures to create something multi-textured and melodically rich. Their first album together, Fleetwood Mac (1975), which features classic tracks such as Nicks’s “Landslide” and Christine McVie’s “Over My Head”, went to No 1 in the US, selling more than 4 million copies.

The success of Rumours, though, took the band to a whole new level of fame. “You don’t see any money for a year after the album’s released,” McVie notes, “so when the first cheques started coming in, we all went berserk and went out and bought Porsches and Rolls-Royces.”

“There’s a picture of the five of us back in the day taken by [rock photographer] Neil Preston, and I always look at it and we’re laughing away, and we didn’t have any idea what was going to happen,” Fleetwood says. “No one could have imagined the success and the hardship and the torment.”

Torment because, just as the band became globally successful, interpersonal tensions were also threatening to tear it apart. Rumours was “the beginning of a lot of trouble and emotional turmoil within the band”, Fleetwood says ruefully. Perhaps it was inevitable for a band that contained two couples. But it’s also one of the abiding reasons why Fleetwood Mac are held in such affection. This was a band that was writing about real people trying to have real relationships and some of their lyrics cut to the quick: “listen carefully to the sound of your loneliness… remembering what you had / and what you lost, and what you had, and what you lost”, wrote Nicks in “Dreams”. “I ain’t gonna miss you when you go”, returned Buckingham on “Second Hand News”, “Packing up, shacking up’s all you wanna do”, he added on “Go Your Own Way”. Nicks dumped Buckingham in 1976, the same year that McVie had an affair with the band’s lighting director – “Ooh, you make loving fun” she wrote, telling her husband the song was about a dog.

“I think it’s part of how people relate to Fleetwood Mac,” Fleetwood says. “In many ways we’ve been too open and too truthful about stuff that is really none of anyone’s business. I think we were quite naive in the way we related a lot of that truth to people other than ourselves.” The outcome, though, he says, “is it’s part of our history and part of a human connection that is now actually a really lovely thing – that people relate to us because we’re not perfect, as many people aren’t themselves.”

The turmoil even extended to Fleetwood, who had an affair with Nicks. Had that sucked him into the emotional maelstrom as well? “That was all for the most part very unknown and it was very private,” he says. “I don’t mind talking about it and I don’t think Stevie would, because we know that that’s part of the story – it’s complicated in terms of the way the logistics of the band worked. To this very day, we’re really lucky that me and Stevie remained very, very dear friends or I’d be answering you very differently.”

The tension between Nicks and Buckingham though was intense, and famously led to a violent confrontation in 1987, in which Buckingham reportedly tried to choke her over a car bonnet. “That whole situation is for Stevie and Lindsey to answer about, but it’s no secret that their journey has been volatile in emotional terms,” Fleetwood says.

Buckingham told Rolling Stone in October that he was given a message that “Stevie never wants to appear on a stage with you again” after he “smirked” during a thank you speech that she gave at a charity concert and claimed that she had given a “him or me” ultimatum to the rest of the band. Other reports suggested that Buckingham’s request to take three or four months off to go on a solo tour had been part of the decision. He took legal action against the group after being asked to leave, but in December it was reported that this had been settled, which may be why Fleetwood doesn’t want to discuss the issue.

“We survived the change we’re going through now,” he says, “none of it is going to be frothed off as, ‘who cares?’... but I have to say that we have two brilliant new members of Fleetwood Mac who are now part of our story, and I truly hope that we will be able to make some [new] music with both of them.”

He’s quick to acknowledge Buckingham’s musical legacy within the band, especially his contribution to Tusk, the 1979 follow-up to Rumours, which he says is his personal favourite. “Kudos to Lindsey for sure, for us not doing a replica of Rumours.” The experimental nature of the double album raised eyebrows at the time. “It’s a very underproduced record, which I hated in the beginning,” McVie admits. “Now I actually really love it.” It has had a critical reappraisal, too, in recent years, and is considered by many to be a classic.

Looking back, Fleetwood admits that the life and times of the band have been so tumultuous that, “if I’d been a singer songwriter, I might have said, I’ve had enough, form a solo band, I’m done... All I can say is it’s a damn miracle [we’re still together].”

Some things remain undone, though, most noticeably a Glastonbury appearance. In 49 years of the festival, the band has not appeared once, although rumours surfaced as usual that this was going to be the year. “We didn’t start them,” he laughs. “Of course, we’ve been asked to play and it’s never worked out.

“I think the legend of Glastonbury and Fleetwood Mac will come true,” he adds, “I think I’ll burn in hell if we don’t do it one day.”

Fleetwood Mac play Wembley Stadium on June 16 and 18

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks