Fiona Sturges: Does gender explain my immunity to Bruce Springsteen's songs of cars, bars and women called Mary?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

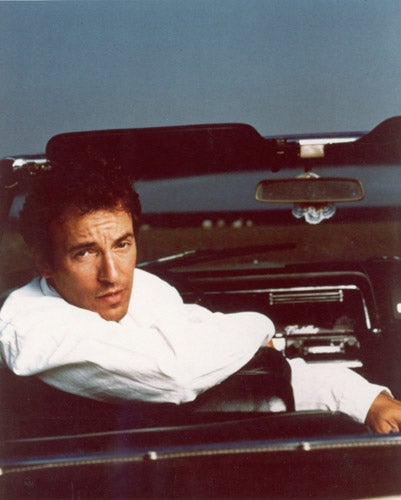

Your support makes all the difference.He is the working-class hero, the champion of the underdog, the everyman in search of the American Dream. His place in the pop canon is irrefutable, his name mentioned in the same breath as Tom Waits, Neil Young, Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan. He's a born showman, a consummate storyteller, a principled poet. So why is it that Bruce Springsteen leaves me cold?

I'm pretty sure that the Boss will sleep soundly at night with the knowledge that I remain unconverted. I, on the other hand, find my resistance puzzling. Good friends with whom I share musical tastes view him with an almost religious devotion. On paper, he seems to embody everything the discerning rock fan (ie, me) would want from a musician. There are times when I like nothing more than stadium-busting, fist-punching, fuel-injected rock'n'roll, from the Stones to AC/DC. Bruce and I should be made for each other.

And yet... Try as I might to engage with him, I cannot. His raspy vocals do nothing for me. His way with a rhyming couplet is evident but his words leave me unmoved. As for that sax, don't get me started. When I hear it, it's like someone is drilling a hole into my brain.

There can, I think, be only one explanation for this Bruce intolerance. It is because I have a fundamental flaw, a defect that cannot be rectified and that sets me at a hopeless disadvantage: I'm not a man.

When he emerged in the Seventies, Springsteen offered a vivid picture of manhood. His songs depicted a testosterone-filled world of car-racing, brawling and partying. He spoke exclusively of brotherhood and the male experience. You can smell the sweat and hear the revving engines on tracks such as "Racing in the Street" or "It's Hard to be a Saint in the City" or "Thunder Road". Sure, there were women. There was Mary, Wendy, Kitty, Janey, Sandy and Rosalita. But while they were appreciated, they were largely viewed from a distance. Both literally and metaphorically, Bruce was always in the driving seat.

Springsteen is, to my mind, the musical equivalent to John Wayne. When I was growing up, Wayne's films were viewed in a spirit of slack-jawed wonder by the men in our house. To my father he was magnificent, dependable and heroic. To me, he was a mumbling, pot-bellied bore who walked like he'd just peed his pants. Now, Springsteen is no mumbler, and I am certainly not casting aspersions on his girth. But, like Wayne, he is a man's man. He's an aspirational figure, a macho symbol of what men think they should be.

Of course, two distinct Springsteens have emerged over the years. The first is rock's alpha male, known affectionately as the Boss, who dresses in denim and leather, whose blood runs red, white and blue, and who sells out stadiums in the clink of a cash register. Then there's the troubled soul behind 1982's Nebraska album or The Ghost of Tom Joad, a troubadour with a direct line to the disenfranchised. I am immune to both. It's not just being a woman that's the problem. I'm a middle-class English woman who, give or take the odd summer job, has always been happy in her work. I don't even drive.

Naturally I'm not saying that you have to be a white, working-class, car-crazy American male to appreciate Springsteen, no more than you have to be a black kid from the LA ghetto to listen to NWA or a nutty Icelander to admire Björk. Social and cultural distance from one's musical heroes frequently leads to greater potency.

To the outsider, the notion of a blue-collar worker struggling to make ends meet in the American hinterlands might seem like the most romantic of situations, conjuring the same atmospheric scenes as Steinbeck and Twain. But for me, Springsteen's visions of burned-out Chevrolets, stagnating small towns and dusty highways don't strike a chord. They don't make me feel wistful or uplifted, or make me want to book a holiday to the mid-west. They seem bombastic, sentimental and clichéd, symbolic of the eternal adolescent who dreams of cars and guitars.

It's notable that among Springsteen's better-known fans, who include Tony Blair, Barack Obama, Nick Hornby, Jeremy Vine, Badly Drawn Boy and Greil Marcus, all of them are men. My friends who adore him are all men. I'm not suggesting that female Springsteen fans don't exist but I've yet to meet one.

There are, one imagines, as many women who love Bruce as there are men that don't. A music-writer friend confessed recently that he has never liked Springsteen, a fact that makes him, to use his phrase, "a big Jessie". Received wisdom has it that, like football and beer, men should love Springsteen. If they don't, it seems their very manhood is called into question.

To me and, I suspect, to many of his detractors, Bruce will forever be the smirking pillock from the video of 1984's "Dancing in the Dark," complete with tight jeans and rolled-up sleeves (check those biceps, girls!), extending his hand to a fan and dancing with her on stage. As gender-bending upstarts invaded the charts and Madonna cavorted in her underwear, Springsteen remained, in his jeans and bandana, an unambiguous, humourless island of masculinity. He may not have worn the headband in 25 years but he remains as synonymous with it as Morrissey is with gladioli, Angus Young with short trousers, or John Wayne with a cowboy hat.

I'm reliably informed that Bruce is now making the best albums of his career. This year, he played the Super Bowl, a gig that was surely destined to be his (watching it, my preconceptions were confirmed. There he was, legs astride, sleeves rolled up, playing his guitar like he was setting to work on a pile of logs). Tomorrow, he plays Glastonbury. Given what I hear about Bruce concerts, it will go on for hours, an extended meditation on the male psyche that will send several-thousand males rushing into a mid-life crisis.

But perhaps I'm being unfair. While gender may exert a degree of influence on our musical tastes, it doesn't dictate it. Any reasonably intelligent woman exposed to the cod-feminist babble of Alanis Morissette knows that. As with physical attraction, great music requires that unique connection with its listener, an indefinable chemistry that can lead to a life-long love affair.

Over the last week I have been listening to the new Eels LP, Hombre Lobo. It is composed and sung by Mark E Everett, a white, American, gravel-voiced soul-rocker who dresses like a Sixties factory worker and who specialises in curiously uplifting songs of love and death. There are songs on all his albums that bring a tear to my eye in a way that Bruce's never have.

Why is that? Perhaps it's just a chemical thing, and that Everett is my musical soul mate. Maybe me and Bruce are just not meant to be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments