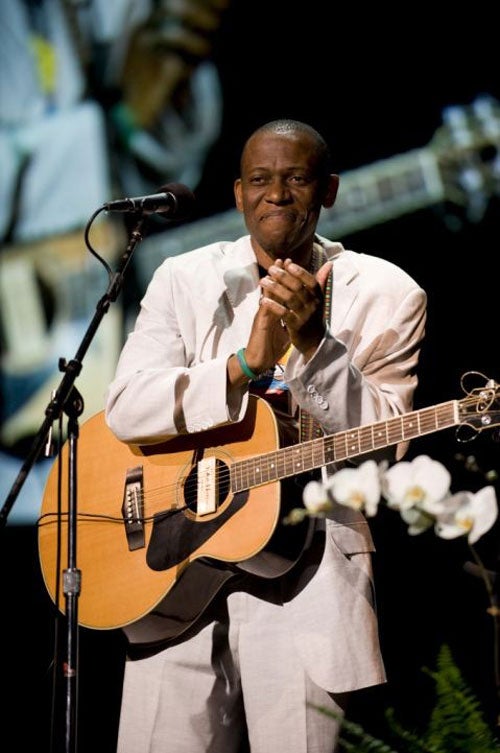

Feliciano dos Santos: hero of the grass roots

His songs about life in a Mozambique ghetto have won him global acclaim and a prestigious environmental award

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a world of charity records and pop superstars attempting to connect with the "grass roots", it can be good to see the grass roots sing back. Bob Geldof might not like poverty in Africa, but those in Africa don't like it much either – so it's pleasing to see one of the continent's residents find his voice in spectacular style.

Hailing from Mozambique, singer-songwriter Feliciano dos Santos, 43, has climbed from the ghetto to world recognition. Disabled by polio, he learned to strum a banjo in a slum, playing the rhythms of Niassa, his home province in northern Mozambique. Using lyrics which campaign for better sanitation in the developing world, he is now a well-known star across the globe.

He has performed everywhere from Brixton's Ritzy to the British Museum, entertained 100,000 for Make Poverty History, and even hooked up with Geldof and Gordon Brown along the way. On Monday, his work for charity finally won the recognition it deserved, as he picked up the Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco.

The Goldman is essentially an "environmental Nobel Prize", named after the US philanthropist Richard Goldman, who in 1990 came up with the idea to honour "grass-roots environmental heroes" from six regions around the world (Santos won the trophy for Africa).

Winners are selected for putting themselves at great personal risk, often after embarking upon significant effort to protect the natural environment. The $150,000 (£75,000) prize pot is the world's largest for grass-roots environmentalists.

Speaking from a hotel room shortly before picking up the gong, Santos describes in halting English – civil is pronounced "sie-fill"; "cholera", "the choleras" – how his world has just been unexpectedly inverted.

When he first heard the good news about the Goldman award, he thought someone was playing an elaborate practical joke.

"I was in my house with my family and someone called me and they said, 'You have won a prize'," he explains. "They said, 'Someone you know will call you'. When that happened, I thought someone was doing my friend's voice and I called his wife. She told me that it was true. I started crying."

Dos Santos is almost maddeningly modest. But his accomplishments have defied all the odds. Inspiration for his music was initially fired up when he was a youngster in Niassa, where most of the one million inhabitants endure a tough, small-village existence. Lack of clean water and sanitation led to Santos contracting polio (one of his legs is five inches shorter than the other) and he was galvanised into proving that less physically-able people can lead successful lives.

"People have these preconceptions that people with physical problems are also mentally disabled. But we are just different," he says. "I didn't just want to sit around and face my problems. I'm not a good, good musician. But people with my problems are often ashamed to perform in front of people, and I thought that it would be good to try."

Santos formed his band, Massukos, in 1992, when it was not so certain that his song writing style would go global. His lyrics trod, and still tread, a literal path through the somewhat artistically arid climate of "sanitation". But, despite crooning lines such as "Mothers, listen to me/grandmothers, listen to me, she doesn't listen to me/the slab [latrine] is so good/the slab is easy to clean", he has won a platoon of fans – his country's president among them.

He founded his own NGO, Estamos, a partner of WaterAid, in 1996, first focusing on water-borne diseases, now aiming the spotlight on water problems for those afflicted with HIV and Aids.

"We are trying to bring water close to them because sometimes they can't walk so much," he says. "Even if they have access to medication, what kind of water will they use to take this medication? Without basic human rights, they cannot do anything." In Mozambique, half the population continues to struggle with below-average hygiene levels.

Santos is not brimming with praise for those Western pop stars with loud, campaigning voices, though. "For me, the concern is how to put it into practice," he adds. "You know, I go to the communities. I know big musicians can do that, because they have prosperous lives: they are famous, they have bodyguards. But when they raise the money, they need to follow it. They need to see where it is being used. That is the most important thing."

With his prize money, he intends to create "a better life for his family" and to translate a body of research on environmental health into Portuguese. He also believes that he will be able to "talk to people more. I will use my voice to talk for people without a voice."

Good causes: Goldman Prize winners

The Goldman Prize honours grass-roots environmentalists. Founded by the US philanthropist Richard Goldman, it has recognised a selection of campaigners from across the world for 18 years. Recent winners are listed below.

* 2007

Ireland's Willie Corduff, from the farming community of Rossport (known as one of the Rossport Five), was given an award after being jailed for protesting against an onshore gas pipeline. Other awards were given to Hammerskjoeld Simwinga, for his work against poachers in Zambia, and Orri Vigfusson of Iceland, for preserving his country's salmon stocks.

* 2006

Olya Melen, from the Ukraine, was honoured for halting a canal which would have cut through one of the world's most valuable wetlands. China's Yu Xiaogang was given the accolade after imagining up a "groundbreaking watershed management programme" to tame the country's powerful river system, and American Craig E Williams was honoured for successfully convincing the Pentagon to stop plans to incinerate chemical weapon stockpiles.

* 2005

The Haitian Chavannes Jean-Baptiste won for founding the Peasant Movement of Papaye, which teaches people sustainable agriculture. Stephanie Danielle Roth from Romania spoke out against the largest open-cast gold mine in his homeland, and Father Jose Andres Tamayo, of Honduras directed a coalition of subsistence farmers who defended their lands against uncontrolled commercial logging.

* 2004

India's Champa Devi Shukla and Rashida Bee were awarded after seeking justice for the victims of a 1984 gas leak in Bhopal city, to which 20,000 deaths have been attributed. Colombia's Libia Grueso picked up the gong for protecting rainforest, while Georgia's Manana Kochladze was recognised for his work in investigating the political process surrounding an huge oil pipeline's construction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments