Fauré - Requiem for a dream

A BBC TV special on Fauré tonight highlights a new theory by The Independent’s Jessica Duchen that he was traumatised by war and the Paris Commune, and that this shaped his view of death – and his magisterial music

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tonight BBC4's Sacred Music series turns to France, and two vital figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Gabriel Fauré and Francis Poulenc. Of all the sacred works of its time, none is better loved than Fauré's Requiem, which dates from 1888 and departed so radically from traditional Requiems that it has never lost its power to astonish us. In the film, Simon Russell Beale wanders through the Madeleine, church of Parisian high society where Fauré was first choirmaster and later "titulaire" (organist), pondering the factors that led the composer to create a piece often termed a "lullaby of death".

Ten years ago I wrote a biography of Fauré, a process that involved the joy of total immersion in his endlessly fascinating music. But, five years ago, I discovered I'd missed something. Returning to Fauré's early life to research a project concerning the opera singer Pauline Viardot, to whose daughter Fauré was briefly engaged, I uncovered a startling aspect of Fauré's psyche that had been ignored by everyone until then, including me, for the simple reason that in 1877 nobody had heard of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Could Fauré's brief yet devastating experience of active service in the Franco-Prussian War have left an indelible impact on his personality and his attitudes towards life, death and God – and therefore on the spiritual aesthetic of his Requiem? Having been increasingly convinced of this, I offered the idea in an interview for tonight's programme, directed by Fran Kemp; she has taken it up; the film makes a powerful case.

When the 1870-71 war broke out Fauré, aged 25, volunteered for the front line; he received a medal for his efforts. But a young man coming back from war was simply expected to return to normal. The horrors he had seen, the loss or maiming of close companions, the violent deaths and appalling injuries that would have surrounded him, all this would probably go undisclosed, and would have to be internalised.

Fauré had been a sheltered youngster; born in 1845 in south-west France, he was the youngest son of a schoolmaster. Aged nine, he went to Paris to attend the Niedemeyer School for church musicians. His teacher, Camille Saint-Saëns, encouraged him to compose; the beautiful Cantique de Jean Racine dates from his school days. In the 1860s he began a modest career as a church organist and choirmaster in Rennes. He was popular with the ladies, got into trouble for using the Sunday sermon as a smoking break and was sacked for turning up to a service in evening-wear straight from a ball. He was not an obvious candidate for the military life.

But he chose to enlist, as we know from a letter to him from his brother Albert, a naval officer: "You strike your blows in a quiet way, but you are not a man of half measures... You did not relish the Mobile Guard... you would risk being bored by doing exercises there for two months with no opportunity for active service. In your militia regiment you will soon be engaged in driving out this pack of northern savages... Honour above all to those who, like yourself, have left a secure job to take up their rifles and march to the frontier."

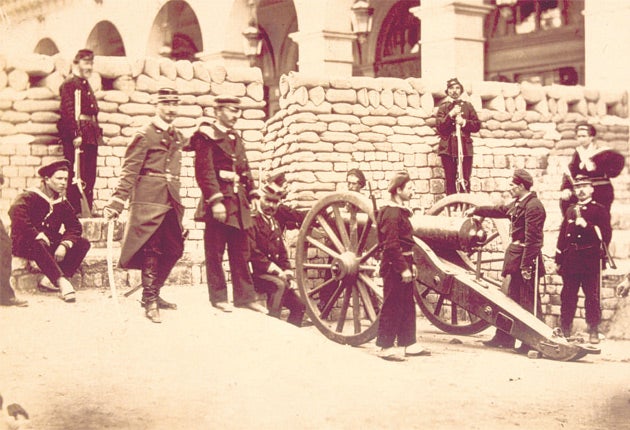

Fauré served as a liaison officer during the siege of Paris – which reduced the French capital to starvation and its butchers to selling dogs, cats and rats for meat. Photographs show the Champs-Elysées lying in rubble; cannons; smoke; row upon row of corpses. Later, Fauré escaped the Paris Commune with a forged passport. After it was all over, he went back to Paris to restart his career. But the story that followed was not straightforward.

In 1872 Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré to the opera singer Pauline Viardot and her family; Fauré spent the next several years courting her daughter Marianne and in 1877 proposed marriage. Marianne accepted – then changed her mind. She seems to have become afraid of Fauré.

Accounts of this time show the young composer suffering bouts of intense depression, severe migraines and dizzy spells in which he had to lean against walls to stop himself falling. During the brief engagement, an occasion when he expressed his unhappiness too strongly led Pauline Viardot to write to him, protesting about his behaviour.

There's little sign of depression, dizziness and fury in Fauré's earlier life. The alteration in his nature has usually been blamed on his disappointment at Marianne's rejection. But suppose that rejection was not the cause of Fauré's depressions, but the effect of them? It was this very quality in him that scared Marianne away. Something else had changed his character. Today these traits might be identified as possibly symptomatic of post-traumatic stress, but not in 1877.

A decade passed before Fauré began his Requiem. He revealed little about his processes and said that he wrote it simply "for pleasure". A requiem was needed for an architect's funeral at the Madeleine; Fauré despised most of the sentimental operatic music the church offered its fashionable congregations. "I'd had it up to here," he said, gesturing, in an interview. "I wanted to do something different." And everything about it is different: its choice of texts (several not from the Requiem Mass at all), its placing of the "Dies Irae" as a secondary element in the "Libera Me", its harmonic language based on plainchant and modal writing; above all, its gentleness, the shimmering "Sanctus", the cradle-like rocking of the "Pie Jesu" and "In Paradisum".

Fauré is said to have been an agnostic, but the Requiem contains a powerful spirituality that suggests a strongly free-thinking stance on its issues. According to Fauré's son, Philippe Fauré-Fremiet, it was the words "quia pius est" ("for thou art merciful") that meant most to the composer. The Requiem presents death as a merciful release from life, through a forgiving God.

It would be reasonable to consider that Fauré's most violent experience, those months in the war, had some influence on shaping his views on death and spirituality – and thus the attitude underlying the Requiem. After witnessing such suffering, a person of his nature was unlikely to espouse the evocation of hellfire and damnation that some composers, like Verdi and even Mozart, chose for their "Dies Irae" settings. His Requiem was not a direct response to the traumas of battle, but it might never have existed without them. His brother was right: in his music, too, Fauré struck his blows in a quiet way, but he was not a man of half measures.

'Sacred Music' is on BBC4 tonight at 7.30pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments