Fall Out Boy: ‘Trump is like the cat on The Flintstones – I just threw him out, why’s he in the house again?’

As the band release their eighth album, Pete Wentz and Patrick Stump speak to Mark Beaumont about overcoming addiction, the dreaded AI future of songwriting (ChatGPT produces the ‘worst’ Fall Out Boy-style lyrics ever) – and Donald Trump

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With a trace of terror in his eyes, Patrick Stump is reliving the ultimate punk rock dilemma. If your bandmate looks like he may have just died onstage, do you keep playing? “His head hit this thing hard, and he was out,” the Fall Out Boy singer says, recalling an early club gig during which bassist and lyricist Pete Wentz took a bad fall. “I was like ‘Is he actually dead, or is he gonna wake up and be p***ed off that we’ve stopped the song?’”

Wentz – provably alive and sporting a flowing dyed-blonde mane where he’d once modelled emo’s most swooned-over fin – laughs along, recalling other show misadventures. There was the night that the stage collapsed beneath them at Chicago’s Knights Of Columbus club. The time three people showed up to watch them play a pizza parlour. Or the riots that kicked off at hometown gigs as this iconic Illinois emo punk band – Stump, Wentz, drummer Andy Hurley and guitarist Joe Trohman, who is currently on hiatus for mental health reasons – began their rollercoaster journey to stadium glory. The sort of memories stirred up as Fall Out Boy arrive in London for a relatively tiny gig at under-the-arches club Heaven ahead of the release of their eighth album So Much (for) Stardust.

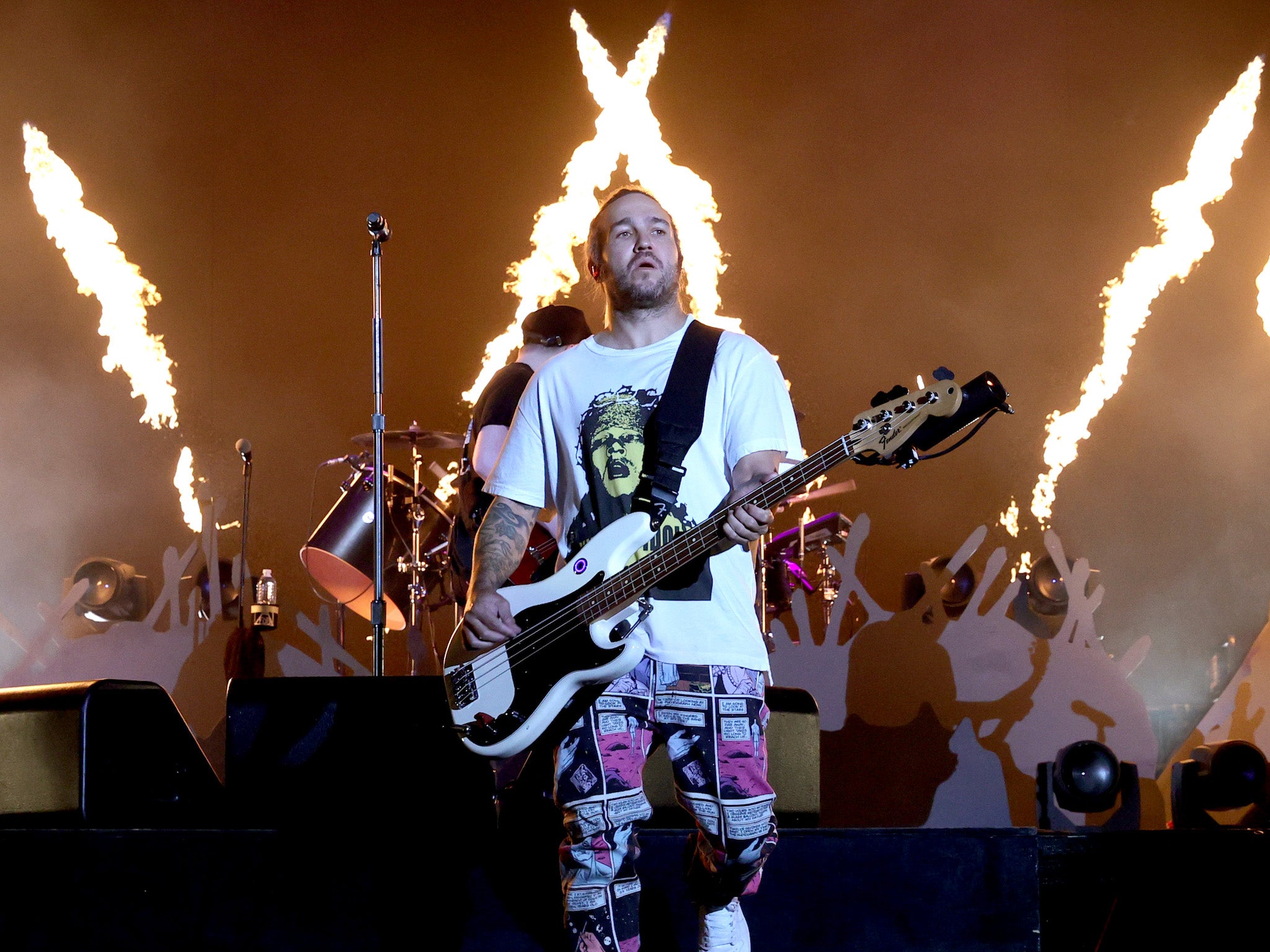

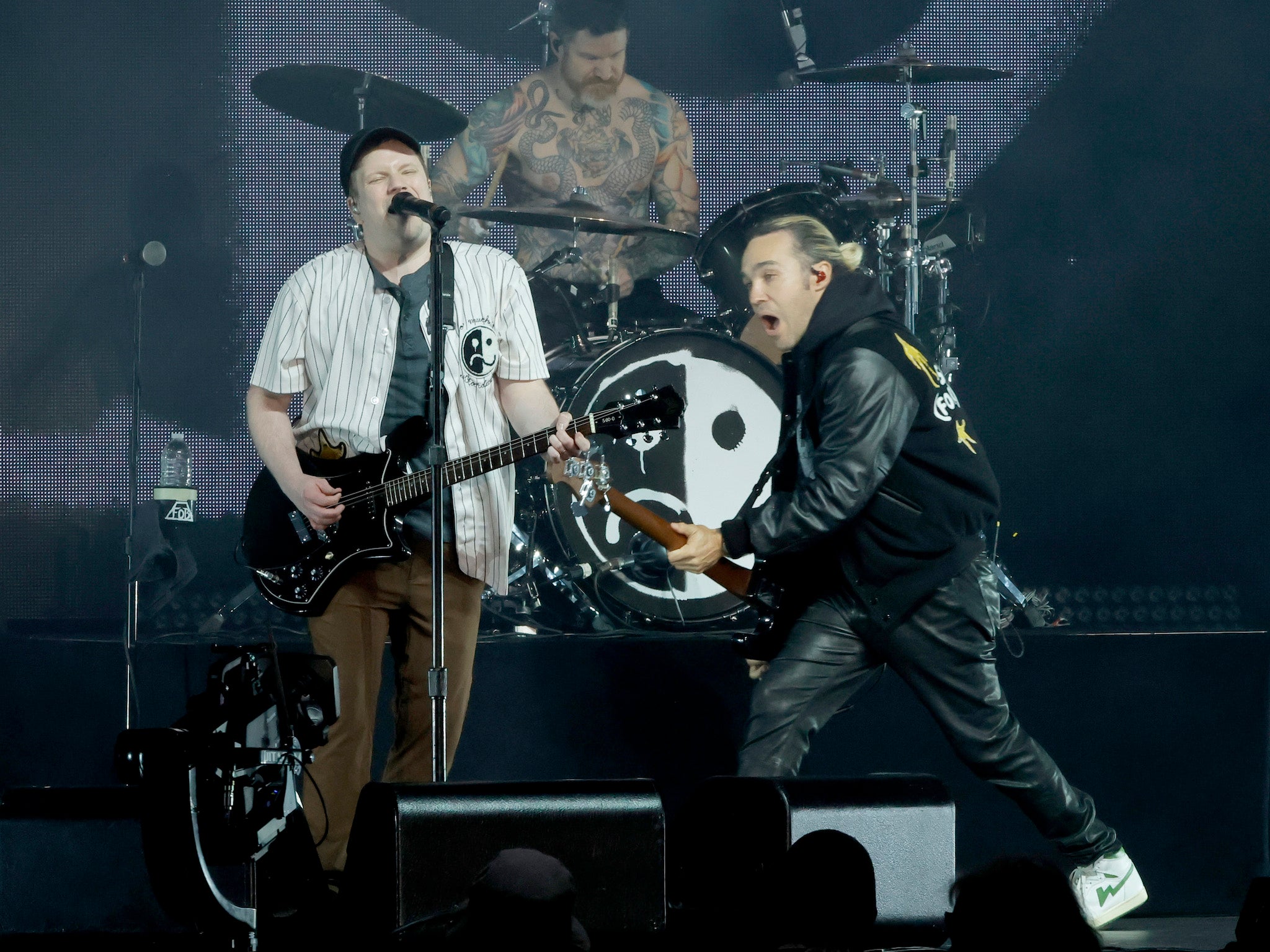

The show itself is a rammed riot; a hi-octane, close-up rock show where the onstage pizzazz comes courtesy of the melodic punk hook lines of “Sugar, We’re Goin Down” and “Dance, Dance”. Wentz steals the show simply by shrugging off his coat to reveal a mesh shirt festooned with roses. It’s a million miles from their recent stadium gigs during which Stump – like a consummate professional – would forge on playing the big emotional ballads despite his entire piano catching fire. “Pete likes to do a lot of the staging,” he explains, “And a lot of times I’m like, ‘You do the thing, whatever’. And then I’ll show up and I’m getting shot out of the floor or something.”

Several hours earlier, sitting in plaid shirts and punk tees in the sort of luxury Bloomsbury hotel that few Heaven headliners have the budget for, Stump and Wentz have clearly taken up residence in a happy mid-ground between their hardcore roots and mainstream superstardom. It’s been a ride, though, not without potholes and breakdowns. Wentz separates their career into two distinct sections. There was the initial 2000s breakthrough period when the catchy punk-pop blasts of their double-platinum 2005 second album From Under the Cork Tree and the 2007 follow-up Infinity on High catapulted them into the emo rock stratosphere. That era ended fractiously, as the follies of Folie à Deux, 2008’s fourth album, saw the band fall apart amid internal wrangles, poor communication and power struggles, alongside Wentz’s long-standing issues with drugs and depression.

Having been in therapy since childhood – “the first time was when my parents separated on my sixth birthday,” he’s said – the bassist, who is bipolar, developed an addiction to the anxiety drugs he was prescribed to combat insomnia and fear of flying. Over what Wentz refers to on the new album as “ten years in a chemical haze”, he attempted suicide by overdose in 2005 and developed so little concern for life that he pulled the trigger on a gun aimed at himself in a drunken game of Russian Roulette. “My friend and I did one pull each,” he confessed to Playboy in 2008. “We’d been drinking and had taken Ambien.”

Since getting clean, though, Wentz better appreciates the shades of life that had been passing him by. “When you’re numbing yourself, you miss out on a lot of the bad stuff, but you also miss out on a lot of the good stuff,” he says. “I think about it like the movie Interstellar, where he comes back to the ship and the other scientist is there with the beard and he was like, ‘Why didn’t you sleep?’ and he was like ‘I felt like that was a waste of my life, I wanted to live, not just sleep through it.’ That is the feeling with [drugs] as well. You have to get out there and live and process, it’s what we’re meant to do.”

In 2013, following a dark but cleansing three-year hiatus, which saw Wentz divorce his first wife, pop singer Ashlee Simpson, and Stump blow most of his savings on an unsuccessful solo career, Fall Out Boy’s second phase kicked off with a US No 1 comeback album Save Rock and Roll. “We just went in and made a record, and we had fun with it. At that moment, there wasn’t a big zeitgeist of, ‘Hey, when’s Fall Out Boy doing another record?’” says Stump. “No one was really asking for one from us or really looking for us to do one. And so, it was kind of freeing, you got to just go in and make this record and, of course, it ended up being a big moment for us.”

Maintaining this devil-may-care attitude has made for an adventurous second act; unlike so many other rejuvenated bands, FOB have played it anything but safe. By 2018’s chart-topping Mania, the band were experimenting with cutting-edge electronica and synthpop – to the bafflement of some hardcore fans and critics. “At times, that record is our most impenetrable and experimental, in addition to it being probably our most pop at certain points,” Stump says. Wentz explains that the album was their attempt at navigating an American music landscape unfriendly to traditional rock bands. “It was like, ‘If we need to figure it out to make it fit the ear puzzle people need, let’s make it the most extreme version of that’,” he says, “and I think you can hear the frustration on Mania.” The band now consider it a “palate cleanser”. “There’s a reason when you’re at the mall and you’re smelling perfumes, they give you coffee grinds in between, because you need to reset,” says Wentz. “That’s what that is to me. It’s coffee grinds. It needed to happen; there needed to be a release of some kind.”

A return to forefronting guitars, and released on their original label Fueled By Ramen, So Much (for) Stardust has been – unfairly – labelled by some critics as a throwback record designed to dovetail with the emo rock resurgence of Willow and Machine Gun Kelly. But considering the album’s grandiose orchestral passages, spoken word interludes and touches of Bruno Mars funk pop dotted among the roaring angst rock, FOB consider it a blending of their various eras and a continuation of their exploratory trajectory, albeit one that pulls the plug on the rise of the machines.

Stump contrasts the record with the “cyborg” sounds of Mania. “I feel like this record is stripping away any of that, it’s very low-tech as a record.” Are they concerned about AIs taking their jobs? Stump laughs, recalling how a family member had once shown him ChatGPT in awe. “They prompted it to write a Fall Out Boy song and then showed me the lyrics going, ‘Wow, look at this!’ I’m going, ‘Those are the worst lyrics I’ve ever read.’” At the current pace of improvement, though, the AIs could be cranking out their own “Thnks fr th Mmrs” in a fortnight, particularly if it finds a way to sabotage Grammarly. Stump nods. “I think it’s very much in the realm of possibility that AI starts writing songs, that the songs start being good, whatever. The thing I wonder, in that Dr Malcolm [from Jurassic Park] way – ‘You ask what you could do, you never ask if you should’ – is why? Art is about expression so if you’re consuming art that has no expression behind it, what’s the point?”

I probably won’t get to score movies for very long because they’ll have technology that does that

To soak up more Spotify money, I suggest. “I understand it from a capitalistic perspective,” Stump argues. “I’m saying as a consumer, as somebody experiencing art.” He references Chris Ofili’s 1996 painting The Holy Virgin Mary, which incorporated one of the Virgin Mary’s breasts rendered in elephant dung. “There was this big controversy in New York about it but the artist was from somewhere in Africa [British artist Ofili is of Nigerian descent] where that specific material meant something specific. It didn’t mean the same thing to us that it meant to him. So, the context was all of the art. If an AI did that, there’s no story behind it. You have no connection with the AI.” He shrugs, a little helpless. “I probably won’t get to score movies for very long because they’ll have technology that does that, but at the end of the day I would hope there’s still art that people are making because that’s the point. That’s the stuff we shouldn’t be automating.”

Tangibility is key to …Stardust. For the album, Ethan Hawke re-recorded speeches from the 1994 romance drama Reality Bites about his dying father showing him the meaning of life in a pink seashell. The kicker is that the shell is ultimately empty; the point being merely to enjoy the meaningless beauty of it. It’s a speech that has always moved Wentz. “Every fall I look older in the mirror, and my kids look the age that I looked [once], and my parents look like my grandparents,” he says. “I don’t have any of it figured out and then I just start thinking about one day I’m not going to exist and one day none of us are going to exist and that existential dread. That quote really sums it up to me, him saying that – there are no answers.”

Hawke’s speech forms the backbone of the album’s aesthetic, from its pink seashell cover art to the shells that were left in packages at key landmarks around the US – or posted to fellow rockers such as Oli Sykes of Bring Me the Horizon – to announce new song releases from the record. “We live in a world where it’s NFTs and avatars and my kids are constantly buying Fortnite skins and stuff,” Wentz says. “I get it, I’ve understood it, they’ve educated me, I’m downloaded on what this all is. But at the same time, I think that there’s something in Fall Out Boy’s DNA of being a little counterintuitive. I would rather do tangible things – I want this record to feel like it’s something you could touch; you could go inside. It’s like a room or something.”

People want to dictate their opinion to each other but really they’re in an echo chamber dictating it to themselves

A room, it transpires, with a view of the end of the world. From lead track “Love from the Other Side” (“of the apocalypse”) to the images of humanity live streaming its own demise on “What a Time to be Alive”, …Stardust is undoubtedly a product of our post-pandemic, pre-Armageddon times. “It feels like the whole world’s about to blow all the time,” Wentz admits. “You’re watching people freak out, people wanna dictate their opinion to each other but they’re really in an echo chamber just dictating it back to themselves. Any time they interact with somebody who has a different opinion they’re freaking out at each other and one of them’s filming the other one. It just feels like everyone’s on edge all the time…it feels like we’re on a precipice.”

Stump characterises the tone of the album as an internalised “simmering rage” against the dying of mankind’s light. “When you’re 16 and your girlfriend leaves you, you can go upstairs to your room in your parents’ house and get angry and throw your things around and just be angry,” he says. “When you’re an adult and there’s an explosion in Lebanon and half the city’s levelled, and you see that on the news and you’re struck with the humanity of it, you have to go and feed your kids and your mortgage is due. You have to internalise, you have to somehow function. It’s like a pressure cooker…you can’t let it out”.

We’re speaking the week before rumours of Donald Trump’s impending indictment over his alleged hush money payments to Stormy Daniels begin to filter out on social media, but FOB are at least optimistic about The Donald’s risk to the future of democracy. “I don’t wanna be the guy that’s wrong but I have this feeling that there’s just so many cases and so many things on top of him at this point it feels almost astronomically unlikely now that he won’t collapse,” Stump argues. “It used to be, ‘Man, this guy’s invincible, he gets by with everything’ but nobody has that much luck. You’d need a f*** ton of luck to get through this right now.” That’s what we were saying in 2015, I remind him. “He’s like the cat on The Flintstones,” Wentz chuckles. “‘I just threw him out, why is he in the house again?’”

While they’re wary of the algorithm’s iron grip over popular tastes – as co-founder of an independent label DCD2 Records, Wentz argues that a lot of great music is being ignored in our “pretty not authentic world” – they’re also encouraged by the open minds of the streaming generation. He grins thinking of his 14-year-old, whose listening habits veer freely from Lil Uzi to Queen. “It’s cool to watch, like watching the cat chase a laser,” he says. “You’re in this era where anything can get big and old songs get big, you could have a minute-long song, you could have no chorus, there’s not a lot of rules. If you have a good song and an interesting perspective, maybe people will at least give it a shot.” Hence, even if humanity itself might be breathing its last, Fall Out Boy plan to keep on rocking.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments