English national anthem: Is Jerusalem the hymn we've been looking for?

In its 100 years, the hymn 'Jerusalem' has been sung with feeling by those of all political colours, says Peter Silverton

England still doesn't have an anthem and it's a worrisome thing. "God Save The Queen" is Britain's anthem, not England's, and, anyway, it's old-fashionedly blood-struck, shares a tune with the US's "My Country 'tis of Thee" and was written as a rallying cry for the anti-Jacobite cause – not a widely popular one these days.

The closest thing to a real national anthem is actually "Jerusalem". Today is its 100th birthday. Both George V and David Cameron have suggested it should be England's theme song and it's certainly the front runner. There were calls for its elevation as long ago as 1927, the centenary of the death of the writer of its words, William Blake.

Mystic, poet, painter, radical, printer, Londoner, Blake did write a poem called "Jerusalem", but the song's lyrics aren't from that one. They are the complete text of a short poem he wrote, some time between 1804 and 1818, for his preface to Milton: a Poem. It was inspired by the apocryphal story that Jesus, as a boy, visited England with his great uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, taking in Glastonbury while he was in the country.

These days, "Jerusalem" is generally seen as a song for radicals, leftists even. Billy Bragg has said that singing it is "the one time I do actually feel pride being English". Yet its origins are at the other end of the political rainbow. It became a song in the depths of the First World War. Blake's poem was published in a 1916 anthology of patriotic verse put together by Poet Laureate Robert Bridges – who then asked composer Sir Hubert Parry to write some "suitable, simple music" for it. It was first performed in the Queen's Hall, London, at a rally for the pro-war Fight for Right campaign.

Later the same year, though, the song took a radical turn, much to the delight of Parry, who had developed doubts about the war. It was picked up and used by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. In the words of the Suffragette leader Millicent Garrett, "I wish indeed it might become the Women Voters' Hymn." Parry was so pleased that he gave the copyright to Garrett's organisation. (The version familiar to us now is actually not Parry's original. It is the 1922 orchestration written by Sir Edward Elgar.)

Like other non-religious songs – "You'll Never Walk Alone", for example, or even Bowie's "Heroes" – it has become a secular hymn. "People seem to enjoy singing it," said Garrett. They certainly did. It was the theme tune for the Labour Party's successful 1945 election campaign, in which its leader Clement Attlee promised the voters that his party would create "a new Jerusalem".

Yet it also has cross-party appeal. It's surely the only song ever to have been sung at the conferences of all three main parties: not just Labour but Conservative and Liberal Democrats. Not the Green party, though – despite that line about "England's green and pleasant land".

There's something in it for everyone. For believers, an evocation of the possibility of a second coming. For socialists, the horror of dehumanising factories. For nationalists, the notion of England as God's chosen acres. For conservatives, nostalgia for the days when those acres didn't have theme parks and roadside litter trails. For feminists, it's the battle anthem of the Women's Institutes – which inherited its copyright, till its expiry in 1968.

Gordon Brown chose it as a Desert Island Disc. As did Ed Milliband, Roy Hattersley and Nelson Mandela's lawyer, (Labour) Lord Joffe. Yet so did Noel Edmonds, Nicole Kidman and CBI director-general Sir Digby Jones. Plus the decidedly Jewish Anthony Julius (Princess Diana's divorce lawyer), Jack Rosenthal (author of Barmitzvah Boy) and Miriam Margolyes (actor). Bend It Like Beckham director Gurinder Chadha, comic genius Frankie Howerd and designer Katharine Hamnett, too.

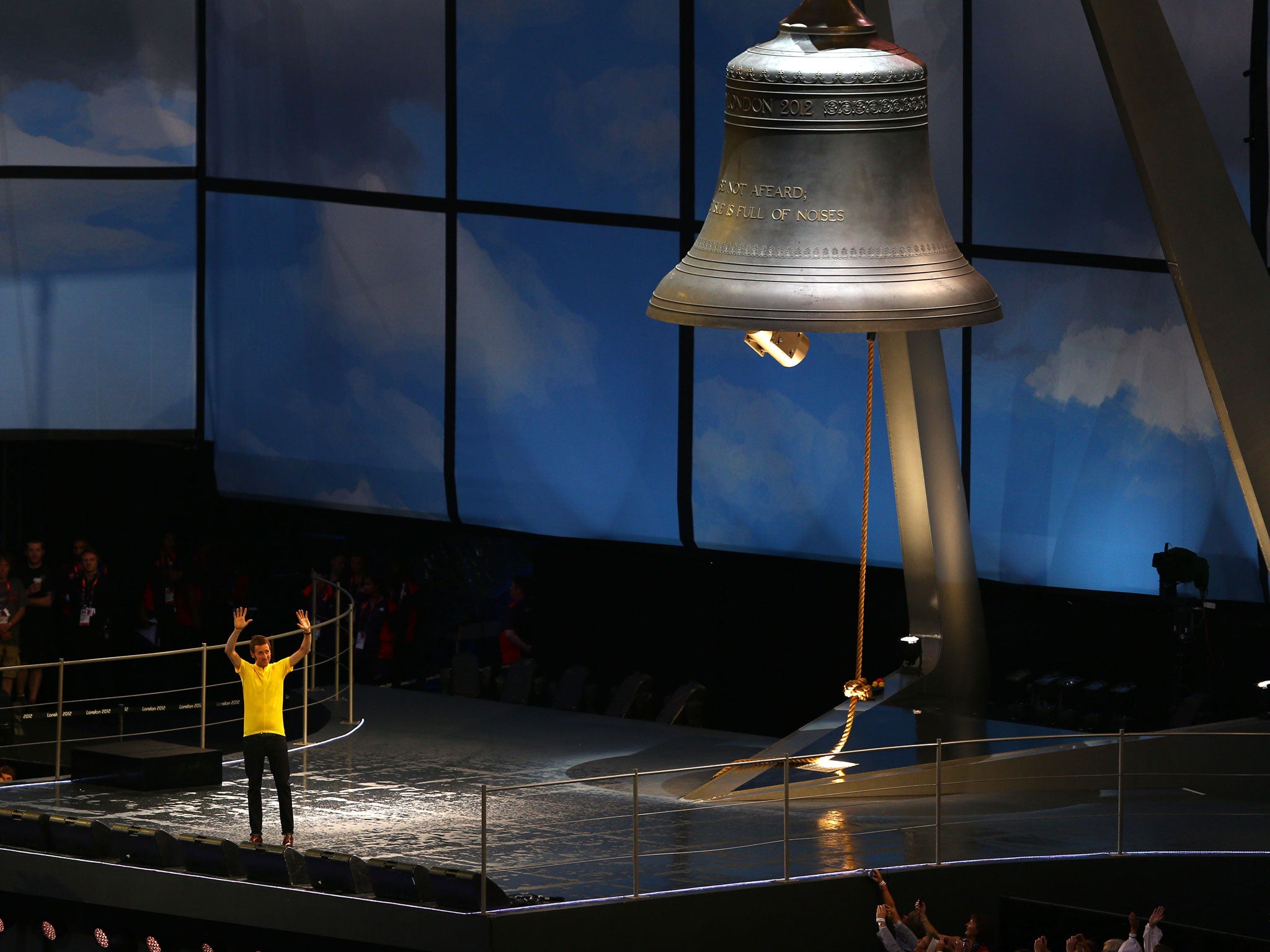

It was played at Ronald Reagan's state funeral. It's the official hymn of the England and Wales Cricket Board. It was used for England's official Euro 2000 song, a top 10 hit. It's sung at the Last Night of the Proms, of course – a tradition that started in the 1950s. It was the opening hymn at the London Olympics, sung by 11-year-old Humphrey Keeper, right after the as-yet unknighted Bradley Wiggins rang the giant bell.

Yet the odd thing is that, unlike most secular hymns, it's a questioning song. It doesn't – like, say, Journey's "Don't Stop Believing" – tell you, comfortingly, what to think. It poses queries and leaves them hanging. It's almost ironic. "And did those feet...?" does, surely, tempt the answer: "Actually, no." An ironic anthem. How more English could you get?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks