Should we still care about Elvis?

As Baz Luhrmann’s enjoyably over-the-top Elvis Presley biopic hits cinemas, Kevin E G Perry examines the star’s complicated legacy with help from the film’s star Yola and queer icon John Waters

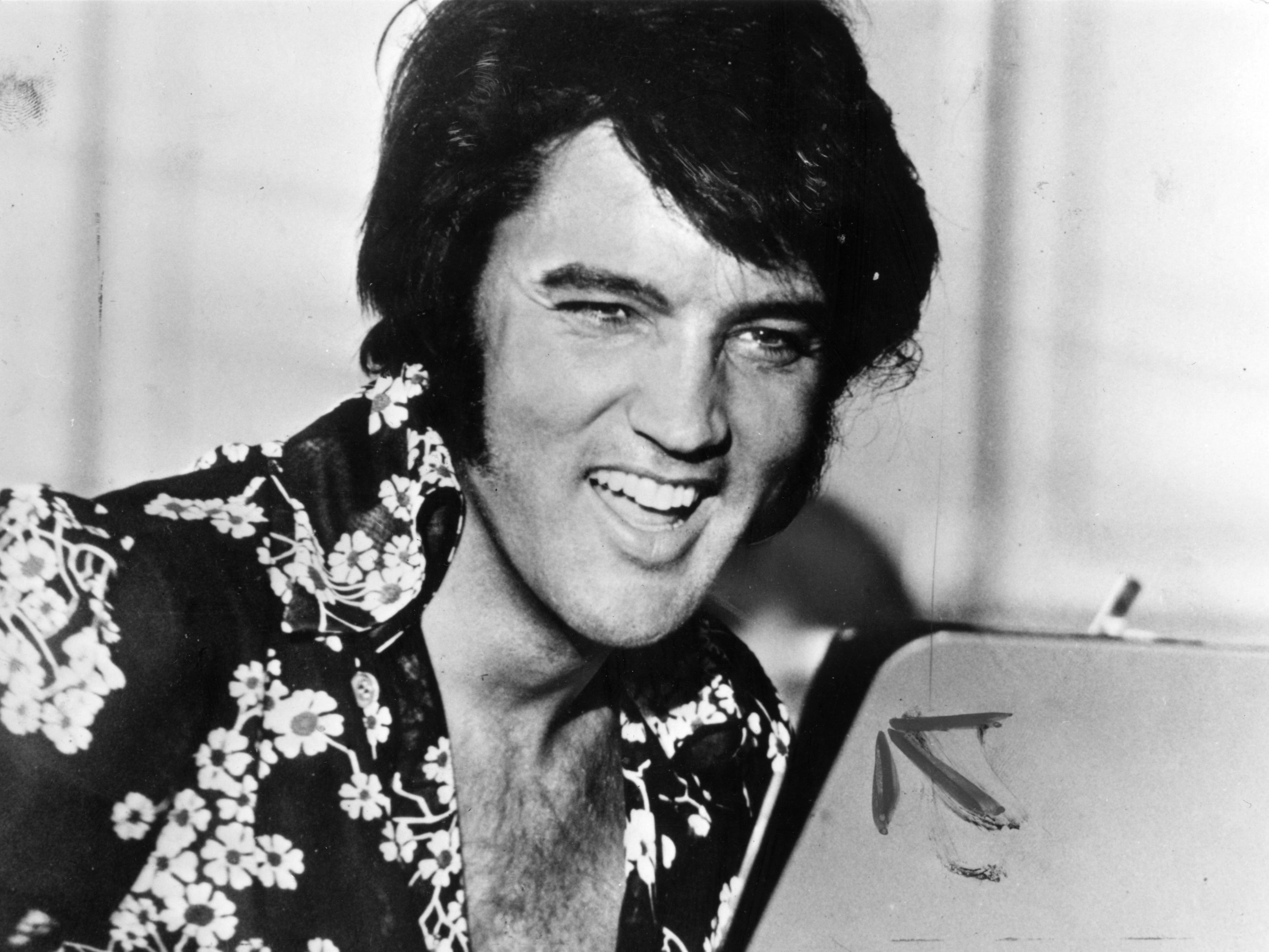

On 16 August 1977, the death of Elvis Aaron Presley shook America all the way to the White House. “Elvis Presley’s death deprives our country of a part of itself,” announced president Jimmy Carter, in a statement that credited the snake-hipped singer from Tupelo with having “permanently changed the face of American popular culture”. Eighty thousand mourning fans turned out to line Presley’s funeral procession in Memphis, but even then there were those who wondered whether the flamboyant showman would genuinely establish a lasting legacy. An obituary by the era’s preeminent rock critic Lester Bangs appeared on the cover of New York newspaper The Village Voice beneath the headline: “How Long Will We Care?”

The answer, we can now confirm, is at least 45 years. The release this week of Elvis, an enjoyably campy biopic from Moulin Rouge director Baz Luhrmann, is just one illustration of the fact that even in 2022 Presley can still command an audience. Earlier this month the Las Vegas Symphony Orchestra brought their show The King Symphonic: The Music of Elvis Presley to London for the first time, while Westminster’s Proud Galleries are currently playing host to a photography exhibition titled Elvis & The Birth of Rock. Less expectedly, last week Sony released a first look at upcoming Netflix series Agent King, an “adult-oriented” animation that for reasons that remain unclear casts Presley as a secret government spy. At least he’ll be putting that suspicious mind to good use.

Both Elvis and Agent King have been produced with the involvement of Presley’s ex-wife Priscilla and the Presley estate, who naturally have a vested interest in preserving and prolonging the legacy of one of the icons of 20th Century Americana well into the 21st. Elvis Presley has been big business for a very long time, and a 2020 Rolling Stone article headlined “Can Elvis Rise Again?” outlined the various ways Elvis Presley Enterprises have been working hard to put Presley back on top. After all, their business depends on it. According to Forbes, at that point, the Presley estate’s income was down 30 per cent on the $60m annually it had been making a decade prior.

Tied up in the question of whether Presley’s fortunes can rise again is the thornier question of whether they should. It’s a fact that his success was built on the work and the showmanship of Black musicians who were never afforded the opportunities he was. The image of Presley as a poster boy for segregation was cemented when Chuck D rapped on Public Enemy’s 1989 hit “Fight the Power”: “Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant s*** to me, you see, straight out / Racist – that sucker was simple and plain.”

However, even Chuck D doesn’t think Presley’s legacy is really that simple and plain. In a 2002 interview he added some nuance. “As a musicologist – and I consider myself one – there was always a great deal of respect for Elvis, especially during his Sun sessions. As a Black people, we all knew that,” he said, referring to Presley’s earliest recording work at Memphis’ Sun Studios. His real issue is with a system that elevated Presley to a position of unique greatness. “My whole thing was the one-sidedness – like, Elvis’s icon status in America made it like nobody else counted... My heroes came before him. My heroes were probably his heroes. As far as Elvis being ‘The King’, I couldn’t buy that.”

To be fair to Presley, neither could he. At a 1969 press conference promoting his return to live performance, after seven years of making increasingly pedestrian Hollywood movies, Presley was referred to as “The King” by a reporter. He deflected the moniker onto his childhood influence Fats Domino with the line: “That’s the real King of Rock’n’Roll.”

That vignette is one of several real-life moments Luhrmann recreates in Elvis, which together make the case for Presley as an icon of integration rather than cultural appropriation. The film repeatedly makes it clear that Presley understood the colossal debt he owed to performers like Little Richard (played by Alton Mason), BB King (Kelvin Harrison Jr) and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup (Gary Clark Jr), whose blues song “That’s All Right” became Presley’s first single in 1954.

British singer-songwriter Yola, who plays rock’n’roll pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe in the film, says that to understand Presley you have to understand his youth growing up in a segregated Black neighbourhood of Tupelo and his early experiences watching performers on Memphis’ Beale Street. “There’s always been one story missing and it’s the foundational story,” she says. “We get superstar Elvis, but we don’t get the thing that makes him. Because it was segregated, we don’t get the story of where it all came from. Him as a child, him as a youth and how we get Elvis.”

As for how Presley himself thought he’d be viewed by posterity, Elvis includes a line he really did say to his backup singer Kathy Westmoreland shortly before his death. “They’re not going to remember me,” he told her, “I’ve never done anything lasting.” Presley considered himself a failure because he’d never made a film that would stack up against those made by his acting idols James Dean and Marlon Brando, but of course it’s hardly true he never did anything that will last. His music still sounds fresh and alive, from the thrill of young rock’n’roll in “Blue Suede Shoes” through to the excess and jumpsuited pomp of “Burning Love” and “Suspicious Minds”. Over 60 years on from its release, Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love” still ranks highly in lists of songs people play for the first dance at their weddings.

Arguably Presley’s most profound impact on popular culture came with a single performance on 5 June 1956. That was the night a 21-year-old Presley appeared on the Milton Berle Show and, for the first time ever on national television, put down the guitar and shook his hips. Even worse for thousands of shocked and appalled parents around the country, halfway through Presley signalled to the band to slow their version of “Hound Dog” down and proceeded to grind to it.

It’s hard to imagine now, in an era saturated by graphic images of every kind, what an impact Presley’s pelvic performance had. In the following day’s New York Times, critic Jack Gould spluttered: “His one speciality is an accented movement of the body that heretofore has been primarily identified with the repertoire of the blonde bombshells of the burlesque runway. The gyration never had anything to do with the world of popular music and still doesn’t.”

While Gould may have ended up on the wrong side of history for that one, host Milton Berle knew from the moment he saw Presley what an impact putting him on television would have. He encouraged Presley not to rein in his performance, telling him: “Let ’em see you, son.” After the show Berle claimed to have received more than half a million letters from outraged mothers calling Presley’s performance vulgar and threatening to boycott the show. He immediately phoned Presley’s manager to tell him about the letters. “I called Colonel Parker,” he later recalled, “I said: ‘All I called you up to say Colonel is this: ‘You’ve got a star on your hands.’”

Presley’s early television performances could have a life-changing effect on those who saw him. “Elvis is why I’m gay,” quips cult filmmaker John Waters to me, recalling watching Presley sing “I Don’t Care If the Sun Don’t Shine”. “The first time I saw him, I knew something was wrong down there – or something was right down there! When I saw him twitching in 1956 singing: ‘We’re gonna kiss, gonna kiss, gonna kiss again…’ Oh my God! I knew right then that this was something that was really gonna cause some trouble in my life.”

The energy Waters felt sitting in front of his television set was spreading all over the country simultaneously. As Lester Bangs put it in Presley’s obituary: “Elvis was the man who brought overt blatant vulgar sexual frenzy to the popular arts in America.” Cultural legacies don’t come much more lasting than that. Every scene of boy band delirium from One Direction to BTS, every moral panic sparked by Cardi B and her “WAP” gyrations or Lil Nas X lap dancing for the devil is an echo of the moment Elvis Aaron Presley shook his hips on national television, and became immortal.

‘Elvis’ is in cinemas from 24 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments