AI Elvis is back in the building: Resurrecting the King for the biggest rock’n’roll hologram show ever

An immersive concert in London later this year will see the return of the King in all his leather-bound, hip-swivelling, Memphis-scented glory. Kate Mossman speaks to the masterminds behind ‘Elvis Evolution’ about how far holograms have come, the need to leave Graceland behind – and why nobody should be all shook up by our insatiable appetite for ‘Brand Elvis’...

Not so long ago, there was much anguish over the ethics of making a hologram out of a dead pop star. There was the question of consent, for a start: the deceased legend had no idea they’d be flickering round the globe in perpetuity. Then there was the problem of developing technology: holographic entities, from Tupac Shakur’s to Roy Orbison’s, were unable to interact or make eye contact. And who would model the body of Whitney Houston, or Amy Winehouse? It was all too creepy to bear.

This November, in an as yet undisclosed central London location, 30,000 sq ft of premium space will be given over to the world’s first Elvis Presley AI spectacular. Elvis Evolution is a joint project between the Authentic Brands Group, the mega corporation that has managed the Presley estate since 2013, and Layered Reality, the tech wizards responsible for the recent immersive shows, War of the Worlds, and The Gunpowder Plot, currently running in the vaults at the Tower of London.

Andrew McGuinness, the CEO of Layered Reality, says his company is “in the memory business” – by which he doesn’t just mean they are making memories, but recreating the past through carefully built-up sensory illusion. The Presley show, he reveals from his office in London, employs, among many other things, “specialists in aroma”. The smell of Elvis? He won’t say what that is. “Smell is an incredibly powerful way of putting people in a place,” he points out. “You may not be aware of all the technology being used, but all your senses will be telling you you’ve been transported. You’ll get the feeling of what it was like to be Elvis.” Expect the humidity of Memphis Tennessee, evoking Proustian rushes of Graceland whether you’ve been there or not.

Artificial intelligence is developing at a terrifying rate. Abba’s Voyage, which has played at a purpose-built stadium in East London since May 2022, has done much to lessen the mawkishness of musical holograms. Pulling on their stretchy motion capture suits, Bjorn, Benny, Agnetha, and Frida proved you didn’t even need to be dead. At the climax of Elvis Evolution you’ll come up against an Elvis avatar modelled from home footage and concert performance mined from the Graceland vaults, most of it apparently never before seen.

“The language is evolving slower than the technology,” McGuinness says, when asked to explain how it works, “but what you will see is a world first. There are a few ways in which that final entity is created, and the main way is to get back to the raw footage – the primary component is authentic sources. So the entity is born of the way Elvis was, and how he moved.”

It is a coup for London to get the show, given that Presley never even set foot here – you’d assume it would go to Las Vegas. But there’s a reason it didn’t. Elvis Presley, according to the people who own him, is in real need of a facelift.

Presley is the only pop star to have become a geographical location, a destination, regardless of whether or not you like his music. And if you’ve actually been to Graceland, as around 23 million people have, you get a fairly powerful sense of who he was as a man. In the summer, the smell of stubble rolls in from the surrounding farms. It is hard to believe he bought the house when he was just 21-years-old; the fact that he moved his parents in from their Tupelo shack, letting them choose the wallpaper, is testament to his youth. Here is the squash court where he played a few hours before his fatal heart attack, on 16 August 1977. Here are reproductions of his countless cheques to local charities. And the silent “meditation garden” is strangely shocking with its cluster of family graves – his parents, Priscilla, and now his daughter Lisa Marie, who died last year at just 54.

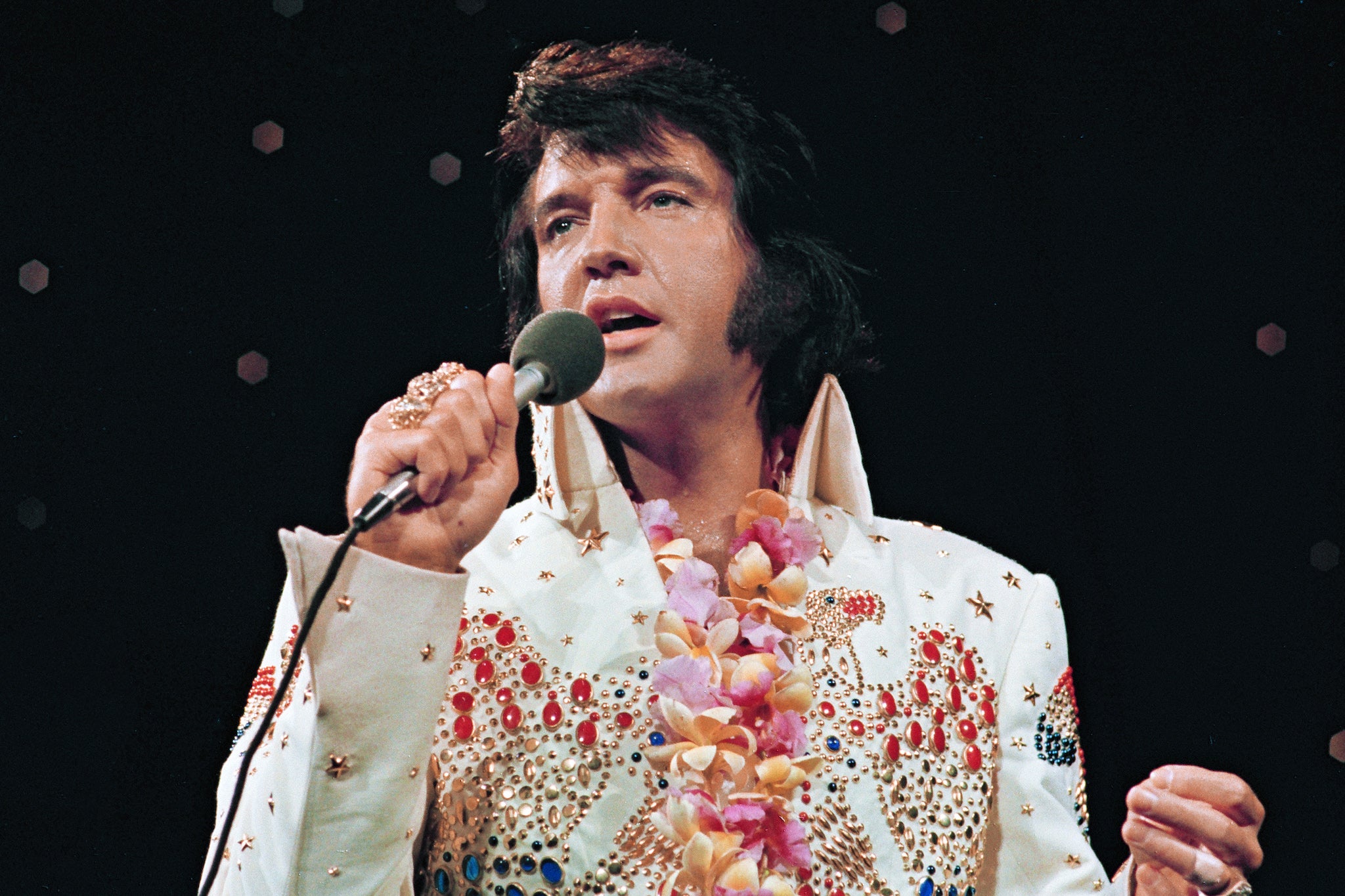

Graceland is a refuge against fame, and evidence of a strange, sealed life. But if you’ve never been there, and you’re too young to remember the impact of his outrageous hips on your black and white TV, Elvis might well be frozen in kitsch, in his Vegas years, and in the image of his doppelganger obsessives. The peanut butter and banana sandwiches, the final fatal trip to the toilet – it was the most undignified end in rock and roll. Bringing the show to London is not just to escape Graceland, but to rework his image and focus on other, more hopeful parts of his life.

Enter Jamie Salter, the Canadian billionaire at the helm of Authentic Brands Group, who started out selling windsurfing goods in the 1980s and now owns 85 per cent of Elvis Presley Enterprises. While the pandemic ruined business for most people, ABG made millions buying up failing corporations such as Barneys, Barnes and Noble, and Forever 21 in New York. If McGuiness is in the “memory” business, Salter is in the “icon” business, as he puts it.

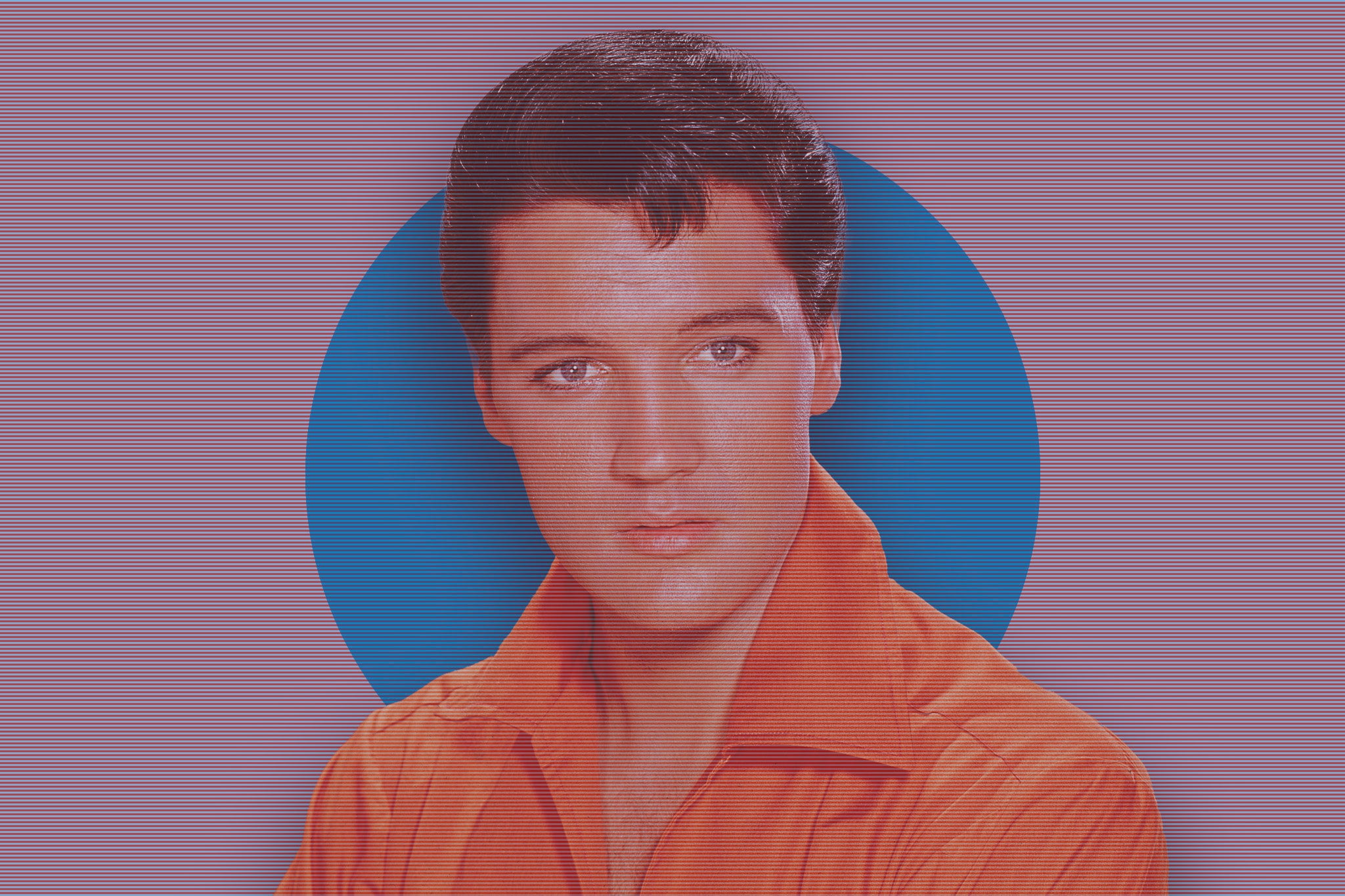

He owns exclusive rights to the names and images of Marilyn Monroe, Mohammad Ali and Michael Jackson as well as Elvis Presley. To him, the young Presley was the epitome of cool, like James Dean: he wants to shift his core audience away from the 1970s jumpsuit Elvis and towards the leathered-up beauty from the 1968 comeback special. Salter stayed out of holograms while the technology found its feet, but in 2017 he hinted, “Why have a hologram when you could have Elvis give you a five-dollar guitar lesson? That’s the kind of thing I’m interested in.”

“All estates are in a constant battle with relevance,” says Eammon Forde, the music business expert and author of Leaving The Building: The Lucrative Afterlife of Music Estates. “With Authentic Brands Groups, the clue is in the name. They’re all about introducing new audiences to legacy brands, and they are treating Elvis like a brand. Core fans age and, yes, die, so new fans have to be brought in. Even American icons like Elvis have to be worked constantly – they are both Coca-Cola and Taylor Swift.” The avatar show, he says, is about “trying to find new ways into new generations rather than super-serving existing audiences, from whom they get diminishing returns. This may upset some music fans, but right from the moment Elvis started working with Colonel Tom Parker, he was turned into a brand!”

Elvis didn’t die. The body did. It don’t mean a damned thing…

Ah, Colonel Tom Parker, the ex-carnival huckster to whom Elvis transferred his financial responsibilities during his lifetime. Parker got 50 per cent of Elvis’s earnings, and just two days after the musician’s death signed a deal giving one merchandise company exclusive access to his name and likeness in return for $150,000 a year. “Elvis didn’t die,” he’s supposed to have said. “The body did. It don’t mean a damned thing…”

When Elvis died, his estate was in terrible shape. Not only was he naive, he was generous and profligate, with an attitude to taxation never seen again in a rock star – for most of his career he was in the 75 per cent tax bracket and had little interest in exploring breaks. But perhaps the most damage was done to his estate in 1973, four years before his death, when Parker signed away royalty rights on his entire back catalogue for a one-off payment of $5.4m. To put it another way, the Presley estate made no royalties from anything he released before that year – which means most of his hits: “That’s All Right”, “Heartbreak Hotel”, “Hound Dog”, “Blue Suede Shoes”, the list goes on and on…

The late Priscilla Presley took back control when Parker died, and accidentally created the model for all successful music estates to come: close family involvement, and a team of hard businesspeople with no interest in pop music whatsoever. Graceland was opened in 1982 to pay off debts – at that point, the estate had just $500,000 in liquid assets. Because they made so little from the songs, merchandise became the focus. All the resulting Elvis-related tat has been burned into the popular consciousness: the shot glasses, the Elvis clocks telling the time by his two swinging legs. Authentic Brands have been slowly buying back the rights to the music: they now own around 75 per cent, but it was never the focus. Elvis may have become the most lucrative estate in music history but one’s sense of his work, and his psychology, have been obscured along the way.

With our show we want you to start seeing him as a man, not an icon in a white jumpsuit

“He started from extreme poverty, from a very small worldview,” says Andrew McGuinness of Layered Reality. “With our show we want you to start seeing him as a man, not an icon in a white jumpsuit. He was extraordinarily polite. He went through constant self-assessment and had very bad periods of what we would now call anxiety. His music always became his grounding when he felt lost. He’d go back to his musical heritage and try to find his way again.”

McGuinness points out that Harry Styles and Miley Cyrus namecheck Elvis as a musical influence and a new generation is starting “from the other end of the story”; Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 biopic Elvis helped too. But you suspect that the very nature of being a fan is different when you’re used to being in daily contact with your idol on Instagram. All entertainment is billed as immersive or intimate, these days – the opposite of an autograph scrawled in a crowd. In our mental-health aware world, the Las Vegas Elvis looks like a victim of the bad old days, pushed on stage by management until he collapses. We probably do want to explore the struggle, the vulnerability, the weakness of Elvis more; the journey of a man who, in McGuinness’s words, “had no right to dream as big as he did”.

The biggest challenge, McGuinness thinks, is pleasing the fanatical hardcore as well as the newcomers. Todd Slaughter, now in his seventies and 30 years on from a triple heart bypass, met Elvis three times and ran the UK Elvis Presley fan club for decades. Slaughter says that the people behind Elvis have thought too narrowly in the past: “Graceland is a private collector of art, if you like, but when it comes to letting out the crown jewels, it’s the same bloody crown jewels every time. The gold-plated mic, the fancy belt from the Las Vegas Hilton. There is a treasure trove in there and no one will ever see it.” He says that the Presley family was the closest thing the US ever had to royalty – but because of their personal problems they were never able to step into the role.

He is surprisingly enthusiastic about the idea of coming face to face with an Elvis avatar in November. “Elvis fans are my age. There are 15 tribute shows going round the UK at the moment and most of them have been doing it for 50 years,” he says. “Unless they do something spectacular – and this could be spectacular, they’re never going to get new fans."

Making shows to memorialise our great musicians has always been a tough one. The days of musty catsuits and Flying V guitars displayed in glass cases are over. Yet rock and roll, as heritage, is going nowhere: like the Renaissance, it all exploded in a finite period of time, then collapsed in on itself and everything that has come along since seems like a copy. Ageing bands book farewell tours because they can no longer run around on stage, while teenagers stream the Stones with no particular interest in who they are, or when it was recorded. If we want to tell the real story of the people who made the music, AI probably is the answer, complete with all those rock’n’roll smells.

‘Elvis Evolution’ will premiere in London in November, with shows also planned in Las Vegas, Tokyo and Berlin

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments