From Ed Sheeran to George Ezra: How the boy next door conquered pop

As a new wave of scruffy singer-songwriters are hailed as ones to watch for 2019, Ed Power asks why these guitar-toting troubadours are so appealing to the mainstream music industry

It was the year the boy next door learned to roar. Ed Sheeran, that superstar in a flannel shirt, left the Rolling Stones and U2 coughing on fumes as his Divide tour soared to a record-shattering gross of £378m. George Ezra graduated from floppy-haired debutante to bona fide superstar, his “Shotgun” single owning the airwaves and becoming the most streamed rock song on Spotify in the UK.

As 2018 ended, meanwhile, a new contender looked set to emerge in Elton John-championed Newcastle troubadour Sam Fender. He was winner of both the Brits Critics’ Choice Award and the BBC Sound Of prize – reliable barometers of talent poised for imminent stardom (previous BBC Sound Of picks include Adele and Sam Smith).

He will face stern competition, however. Kindred strummers Dermot Kennedy and Lewis Capaldi are also tipped to break big in the months ahead, each bringing their own blend of soulful lyrics and sensitive falsettos. The boys are back with a vengeance.

None of these artists are soundalikes, exactly. But they do have a great deal in common. For starters, they have a grounding in the old-fashioned art of standing alone on stage with a guitar and crooning their hearts out.

Image-wise, moreover, all of them could have dropped from the same production line. With his tatty T-shirts and high-street jeans, Sheeran has pioneered the lad-from-up-the-road look. In the past 12 months, however, he was pushed hard by 25-year-old Ezra and his gap-year backpacker chic. Twenty-two-year-old Capaldi, who has just wrapped a sold-out tour, looks, for his part, as if he’s tumbled out of the student union bar on two-for-one night.

What 2018’s batch of bloke emoters conspicuously lack is the traditional whiff of brimstone. Sheeran might shoulder the hopes of the UK record industry – he was the fifth most streamed performer globally on Spotify this year – but it’s a stretch to imagine teenagers gazing starry-eyed at his poster on their bedroom wall.

Nor does George Ezra exude lock-up-your-daughters mystique. Leave your daughter alone with George Ezra and you’d probably return to find him helping her with her homework. These stars are unassuming and down to earth – devoid of guitar music’s untrammelled rawness. They are strikingly desexualised.

In other words, “nice” is the new rock ’n roll. A sense of how important it is to be clean-cut can be gleaned by comparing the success of Ezra with the underwhelming return of soul bawler Hozier, whose tortured Catweazle persona feels suddenly out of step. A shave and a cropping of his man-bun would, you suspect, go a long way.

“All music tends to have its phases,“ says Amy Wadge, the Wales-based songwriter who co-authored some of Ed Sheeran’s biggest hits, including the 2014 number one “Thinking Out Loud”. ”We’ve had Britpop and the dominance of the bands for quite an amount of time. The boy with the guitar has always been there but Ed has probably blazed a trail. That has opened the floodgates.

“My theory is that because of the internet the easiest way to deliver a song is to sit in front of a webcam with just a guitar and a voice. That is the simplest approach and seems to be connecting with people.”

Sheeran, whose 2010 debut EP Songs I Wrote With Amy consisted of five tracks composed collaboratively with Wadge, has been upfront that relatability is central to his appeal. When I interviewed him in 2011 as he was on the cusp of stardom, he was very clear that building his following one fan at a time via YouTube had created a unique connection; one no amount of record company marketing money could replicate. From the outset, approachability was baked into the brand.

“I can make a video for no money, put it on YouTube, tell fans about it on Twitter and Facebook,” he said. “As long as your fans stick with you, what everyone else thinks doesn’t matter. That’s the best way to be. You have longevity. If you find success from building your own foundation, you don’t need the record company. Atlantic could drop me tomorrow – I’ve still got the fanbase that got me here. They got me into the charts before I was signed. It’s a better position to be in.”

“As Ed would say himself,“ says Wadge, ”his charm is that, although he has this extraordinary talent, he looks like the guy next door. In all our years he has never dressed differently. He looks like the average guy, who happens to be talented. Back in the day our pop stars were presented to us in a certain way.

“That has changed with reality TV. People want to see someone they feel they know. That works so well for Ed. He was connecting on YouTube with people long before the rest of the world knew about him.”

With a substantial following in their corner from the start, boy rockers have weathered the inevitable media slings and arrows. Poking fun at Ed Sheeran has been a national pastime since approximately five minutes after he became famous. Yet opprobrium appears to have harmed him not one bit. He was a hugely controversial Glastonbury headliner in 2017 but strutted away unrattled, his reputation, if anything, enhanced by the manner in which he coolly ignored the naysayers.

Compare that with the vitriol directed at more “conventional” punching bags such as Bastille and Mumford & Sons – and how it has created a divide between their (admittedly vast) hardcore audience and a world that otherwise regards them as a joke without a punchline.

The free pass given to the cheerfully unglamorous Sheeran and his ilk arguably flows from the deepening intertwining of pop and social media. In the age of Instagram, it’s harder for stars to present an unrealistically heightened version of themselves. Rather than fight this, the smartest lean into their “ordinariness”. Which is why Taylor Swift can get away with – and indeed accentuate her celebrity by – posting images of her cats, where it would have been unthinkable for Madonna to do the equivalent a generation previously.

All of which has created a perfect conditions for dorky male pop stars. George Ezra has been honest that, had he started out in the Eighties or Nineties, he is unlikely to have had a shot at fame. He simply can’t pull off the detached cool that was once de rigueur.

“It wouldn’t work for me,” he told me last April, as his second LP, Staying at Tamara’s, was beginning its conquest of the charts. “There was a point on the first record where it started to do well. I thought, ‘s*** – I haven’t thought about who I’m being… maybe I will have to [adopt a persona]’. In fact, I’ve never had to. Twenty years ago, very few people were living the life they were saying, I think. I have the luxury to admit, ‘I don’t party… but here’s my record’. Twenty years ago, I would have either been ironically cool for admitting that – or you wouldn’t have gone near me.”

“Perhaps it comes back to that quote about country music being, ‘three chords and the truth’,” says Songwriting Magazine editor Duncan Haskell. “We want to believe in what musicians of all genres are writing about, and maybe that’s easier if they look a little less glamorous.”

Commercially, the boys of strummer have gone where few singer-songwriters have previously ventured. Sheeran’s Divide tour holds the record for highest grossing run of dates in a calendar year, knocking the previous champion, The U2’s Joshua Tree concerts, into a cocked beanie-hat. The 2017 album itself (styled “÷”) moved 672, 000 units in its first seven days in the UK – the third highest total in chart history and extraordinary in our age of flatlined record sales. That same week he had 16 tracks in the singles top 20 and nine in the top 10.

Ezra, for his part, clocked up the fastest-selling long player of 2018 with Staying at Tamara’s. Even “lesser” boy troubadours have enjoyed a blockbuster rise. James Bay’s debut album, Chaos and the Calm, debuted at number one. And despite a zero-star review from the NME – prompting his dad to ring up to complain – Tom Odell’s first record likewise topped the charts. Sam Fender, meanwhile, has already racked up 1.2 million streams with his Tom Petty-esque rocker “Poundshop Kardashians”, despite still being relatively unknown.

Understandably, none of the male singer-songwriters to emerge post-Ed the Conquerer are keen to be pitched as a “Son of Sheeran” – a Northern Uproar to his Oasis. At the same time, they don’t want to be construed as taking potshots at the Ginger One. That’s another way in which the present crop stand apart. They are unfailingly polite and don’t do feuds.

“It [the Sheeran comparison] is a funny one. I don’t know if I should ever receive it as a negative thing, as he’s massively successful,” says Dermot Kennedy, the Dublin singer-songwriter shortlisted on this year’s BBC Sound Of countdown. “It has happened for sure. You get things like, ‘could Dermot Kennedy be the Irish Ed Sheeran?’. It would lead you to believe they can’t have got too involved in listening to the music.”

One unavoidable fact is that all of these artists are male. Where is the female Ed Sheeran? Why no Georgina Ezra? What does it say about the record industry – and the music-streaming public – that we can take these sloppy-grinned troubadours to our hearts while finding no room at the inn for the female equivalent?

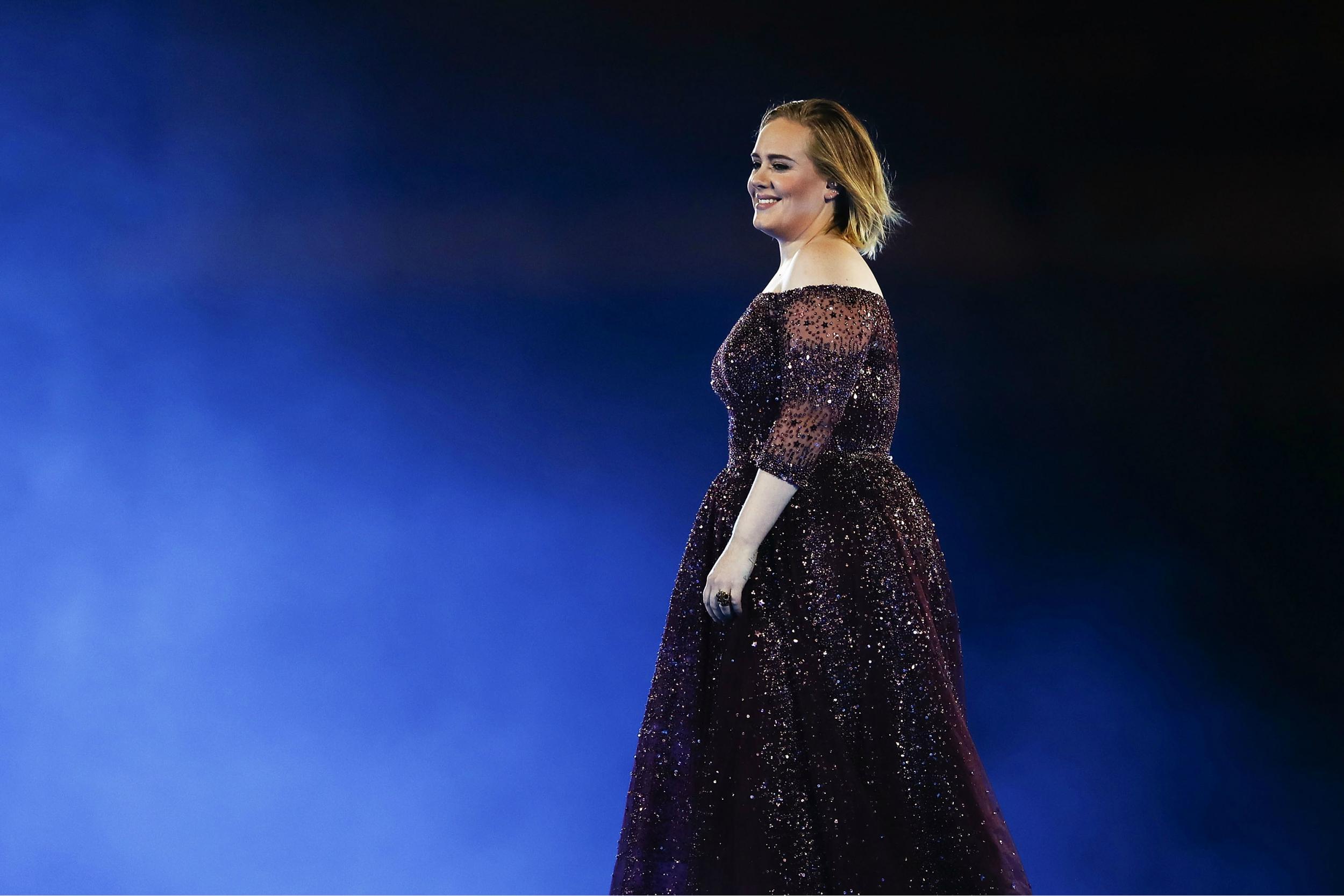

Adele is, for instance, every bit as much a phenomenon as Sheeran, yet she fits into the pre-existing tradition of gale-force soul belters. She doesn’t get to rip up the manual and write her own rules. Her triumphs are on someone else’s terms, not her own. It would certainly be unthinkable that she could go on stage looking as if she’d just tumbled out of bed, as Sheeran did on the Divide tour. Compare also the buzz around Fender with the lack of excitement over female-fronted Wolf Alice winning the Mercury Prize for year’s best album.

“No matter how you want to colour it, it isn’t the same for women…it just isn’t,” says Wadge. “So many of our female pop stars have to be presented in a certain way. If they don’t, they get slated. As much as I wish it weren’t the case, it’s just harder.”

She recalls her own years as a struggling singer-songwriter and how her gender subtly became an issue. She was asked to lie about her age – “I was 25 for a very long time” – and to keep the fact she was married secret.

“It was a very different era,“ she says. ”Nonetheless, I always felt at that time that there was room for only a few females. My contemporaries were people like KT Tunstall, who was smashing it and was definitely better than me. There was an element of , ‘Why would we need you? We already have a girl with a guitar.’ With guys, I don’t think there’s the same expectation. I do like to think it’s changed and that it’s become more equal across the board.”

Still, it arguably remains the case that a young woman with a plectrum is put into a box far more quickly and has less opportunity to define herself than, say, Ed Sheeran. Contrast how he parlayed YouTube popularity into a global following with the fate of Dodie Clark. As with Sheeran, she started out posting heartfelt songs online. However, and despite her considerable live following, she has been categorised not as a songwriter but as a social media star – a novelty act, by any other name.

“I’m a woman and a ‘YouTube star’ in quotations,” she told me earlier this year. “Being taken seriously is very difficult.”

The other guitar-strumming pachyderm in the lobby is race. Almost without exception, these young male songwriters are white and typically middle class. So, too, are their audiences. Michael Kiwanuka, one of the few non-white songwriters to break through, found the situation so confounding that in 2016 he even released a single titled “Black Man in a White World”. “The fact no black people were coming to my gigs made me realise we’re more segregated than we think,” he said at the time.

It’s just a theory but one factor in the breakthrough of these artists may be that audiences are far less judgemental and sneery than a generation ago. David Gray has spoken of his early frustration in trying to persuade the UK music industry to take him seriously.

“People were so cynical here,” he recalled of his early struggle. “I couldn’t get anywhere. It was real cynicism you know. A real ‘impress me… this will never work, an earnest troubadour with an acoustic guitar’.”

He would lay his heart out and people would stare and laugh. In the end he had to go to Ireland – where U2 and the like are part of a far more earnest tradition – to be accepted (this allowed him return to the UK a superstar with White Ladder). But something has changed in the interim. Nowadays earnestness – the more bumblingly real the better – has acquired a cachet. Or at least it has if you’re a personable chap in his twenties.

“There is a level of expectation that if you are going to sing about something, it should be something that matters,” says Wadge. “We see everything up close and personal. There’s no mystique any more.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks