How Don Henley bounced back from Eagles’ messy breakup to make a pop classic

Has there ever been a more potent song about nostalgia? Ed Power looks back at the story of ‘The Boys of Summer’, 40 years after its release

The best song ever written about nostalgia starts with a simple drum pattern, followed by a mournful guitar loop. Then a voice breaks in, rasping with sadness: “Nobody on the road/ Nobody on the beach”. You feel what it means, deep in your bones: the good times are over, never to return. It’s a feeling everyone experiences at some point in their life – yet one all too rarely captured in music. The tune is Don Henley’s autumnal chart-topper “The Boys of Summer”, which marks its 40th anniversary on Saturday. This song about growing old has itself grown old.

“The Boys of Summer” – which reached No 12 in the UK charts in 1984 and went top five in the US – has woven itself into the tapestry of popular music. In it, Henley, who had recently split from Eagles, laments the death of hippy idealism in the flash-pop glare of the go-go 1980s. Today, though, it transcends the immediate context of its release. Listened to in 2024, Henley’s sorrow for the passing of the prime of his life – “I feel it in the air/ The summer’s out of reach” – has a universal quality. It speaks to the chill everyone feels as the years whirr past, steadily at first, then faster and faster.

If careworn at the edges, “The Boys of Summer” has lost none of its bittersweet ache. “The song takes you to a place that reminds you of your youth,” says Jonny Spalding of the Lightning Kids, a London electronica group who covered the tune in 2022. “We were drawn to ‘The Boys of Summer’ initially because of the storytelling and how it fitted into the themes of youth, long-lost teenage summers and underlying nostalgia”.

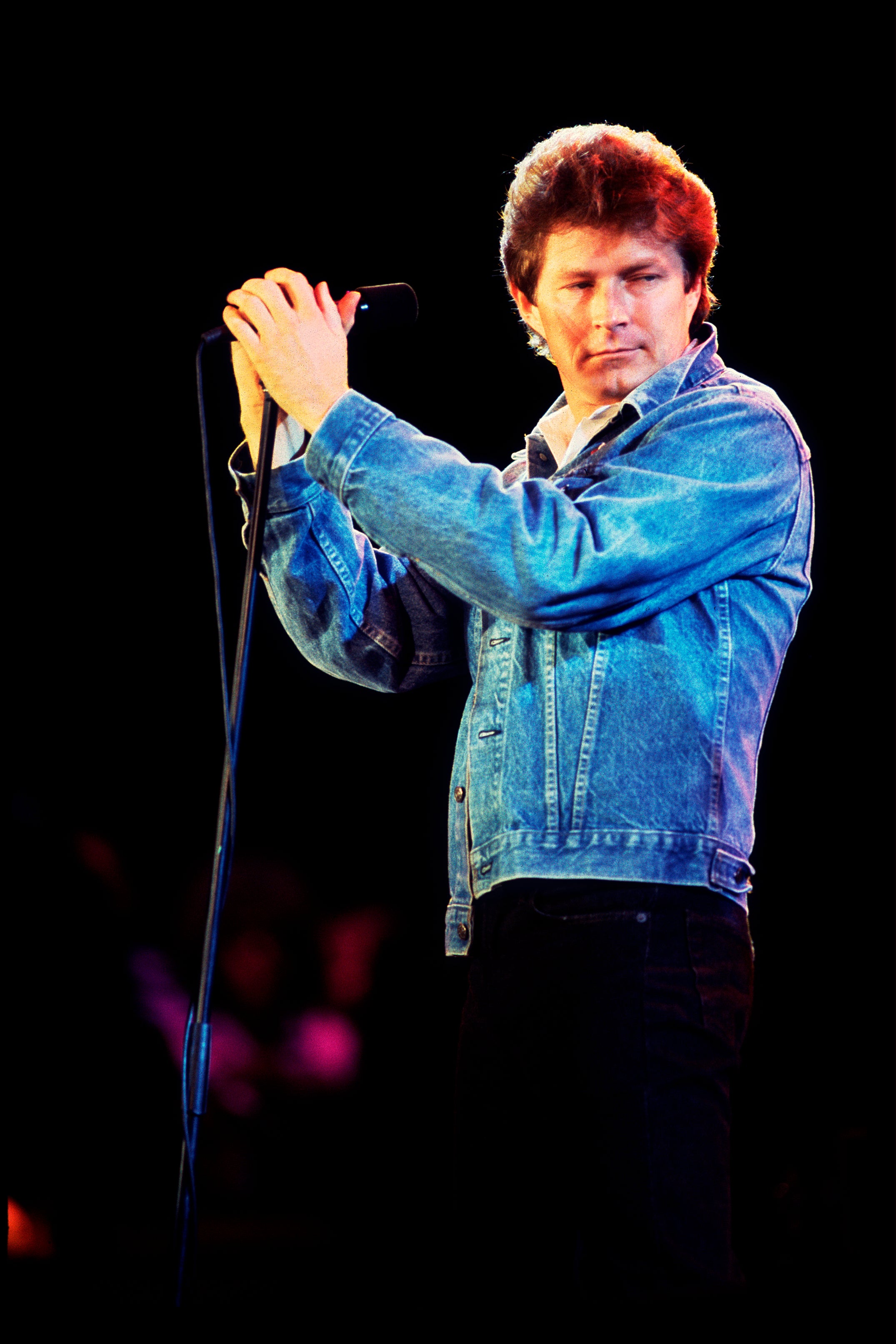

Before “The Boys of Summer”, Henley was reeling from Eagles’ messy implosion in 1980 – when personal differences between band members, exacerbated by fame, money and drugs, came to a head. It was a soap opera that ended up in bitterness, recrimination, and even threats of violence – Eagles’ last ever show (before their 1994 reunion) had seen singer Glenn Frey square off against guitarist Don Felder, promising “I’m gonna kick your ass when we get off”. It was a runaway train, and Henley couldn’t get off fast enough. But the naturally pensive singer and drummer also wondered if his best days were behind him. He was 36 going on 37, which, in the early 1980s, was pensionable age for a rock star. Did he have anything left to say?

Then, out of the blue one day, he received a call from Mike Campbell, the long-serving sideman to Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Campbell had become obsessed with the LinnDrum, a cutting-edge drum machine created by electronic music designer Roger Linn (whom Campbell got to know through a mutual acquaintance, singer Leon Russell). “It had a bunch of live sounds that you could mix together like a drum machine and make your own patterns,” Campbell would remember. “It was pretty revolutionary at the time.”

In later years, the LinnDrum was embraced by pop producers such as Stock Aitken Waterman and Trevor Horn, and became associated with a tinny, chirruping sound (it also features memorably on A-ha’s “Take On Me”). In 1984, though, Campbell was one of the first musicians to get his hands on one of the devices. Kid-in-a-sweetshop style, he put together the instrumental demo of what would become “The Boys of Summer” – a montage of ennui-filled grooves topped off with that autumnal riff.

He presented it to Petty’s manager Jimmy Iovine, but they rejected it as “too jazzy” for what would become the Southern Accents album. Iovine suggested he bring it to Henley, who was looking for material for a new solo album (his 1982 debut, I Can’t Stand Still, had failed to make the US Top 20).

Campbell had never met Henley but, concluding he had little to lose, paid him a house call. “We sat at opposite ends of a long table, and he put the cassette on,” Campbell recalled in a video he posted to YouTube in 2021. “He didn’t tap his foot or move his head. Just sat there, with his arms folded. He listened all the way through. I thought he hated it. He goes: ‘OK, I’ll see what I can do with that.’ And I left.”

Despite his apparent lack of enthusiasm, Henley felt the song had promise. “People I work with will tell you that I’m not very demonstrative, at least until most of the pieces fall into place,” he told Louder Sound. “I liked the percussion Mike had created with the machines. I liked the guitar sounds a lot, and the synthesiser lines. All the layers merged into a texture that was really evocative. It just needed a little arranging. Once I’d figured out what went where, the melody and the lyrics began to flow pretty quickly.”

If the riff and drum machine pattern formed the outline of the track, it was Henley’s lyrics and the resignation in his vocals that gave the song its power – the way he imbues lines such as “don’t look back, you can never look back” with a mix of ruefulness and yearning.

It just struck me as ironic, paradoxical, with a little touch of nostalgia

Early in the recording process, Henley needed inspiration, so he got in his car and headed into the great blue unknown of Southern California. It was as he was cruising down Los Angeles’s Interstate 405 highway that he saw a 1979 Cadillac Seville – “the status symbol of the right-wing upper-middle-class American bourgeoisie”, as Henley would later put it. On the back was a “Deadhead” sticker – this Reaganite on wheels was a fan of the ultimate embodiment of the hippie dream, the Grateful Dead. And then it came to him: the line that would apply the perfect finishing touch to the track he was struggling to complete: “Out on the road today/ I saw a Deadhead Sticker on a Cadillac.”

“It just struck me as ironic, paradoxical, with a little touch of nostalgia,” Henley would recall. “And it went right into the song.”

Soaked in melancholy, “The Boys of Summer” is the work of an artist who had been reflecting at length on his past and his misgivings over paths not taken. There was a lot to think about in the years since he and Frey formed Eagles, having first worked together as backing musicians to Linda Ronstadt in 1971. Henley had arrived from small-town Texas with a chip on his shoulder which, paired with tensions between Frey and Felder, meant that by 1980, the project was untenable. Asked if the group would ever play together again, Henley replied, “When hell freezes over”. (This would become the name of their 1994 comeback tour).

He had other demons, too, and his dark side had become public knowledge after his arrest in November 1980, when authorities found drugs and a 16-year-old sex worker suffering from an overdose at the rock star’s Los Angeles home. Henley would later claim that he had thrown a party to help him deal with the despair over the implosion of Eagles.

Today, such a scandal would surely have been the end of Henley. But in the 1980s, he was able to put it behind him – though it inspired his 1982 single “Dirty Laundry”, in which he painted himself as the victim of bad press (“People love it when you lose/ They love dirty laundry”). Some of that self-pity seems to have carried through to “The Boys of Summer”, where the narrator pines for a love interest he suspects he may never see again. It’s wide-screen woe-is-me, topped off by Henley’s flinty drawl.

The song is often assumed to have lifted its title from Roger Kahn’s 1972 bestseller about the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team. Henley was a baseball fan but claimed to never have read Kahn’s memoir about the 1955 World Series-winning Dodgers of his youth. Instead, he said that the title came from a line by Dylan Thomas: “I see the boys of summer in their ruin.” (Thomas’s poem, “I See the Boys of Summer”, explores the same theme of sadness and loss that informs Henley’s lyrics).

Whatever the inspiration, the song’s blend of introspective lyrics and rasping, mournful vocals set it apart in the bright, bouncy world of 1980s radio. Meanwhile, its use of synthesisers put daylight between Henley and the country rock with which Eagles were synonymous.

It also benefited from a memorable black-and-white video. Directed by French fashion photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino in a “French new wave” style, it juxtaposed a grouchy-looking Henley singing to the camera with images of a man at three stages in his life: childhood, youth and middle age. Together, video and song proved commercial dynamite and the single charted on both sides of the Atlantic, winning Henley a Grammy for Best Male Vocal Rock Performance.

“I think it’s the mark of a truly great singer that he can take what could have been a decent pop song and transform it into a genuine anthem. His range, his intonation, delivery and intensity are on show for anyone with ears,” says Rob Beattie, bassist and singer with Eagles cover band the Alter Eagles. “It’s an extraordinary vocal performance.”

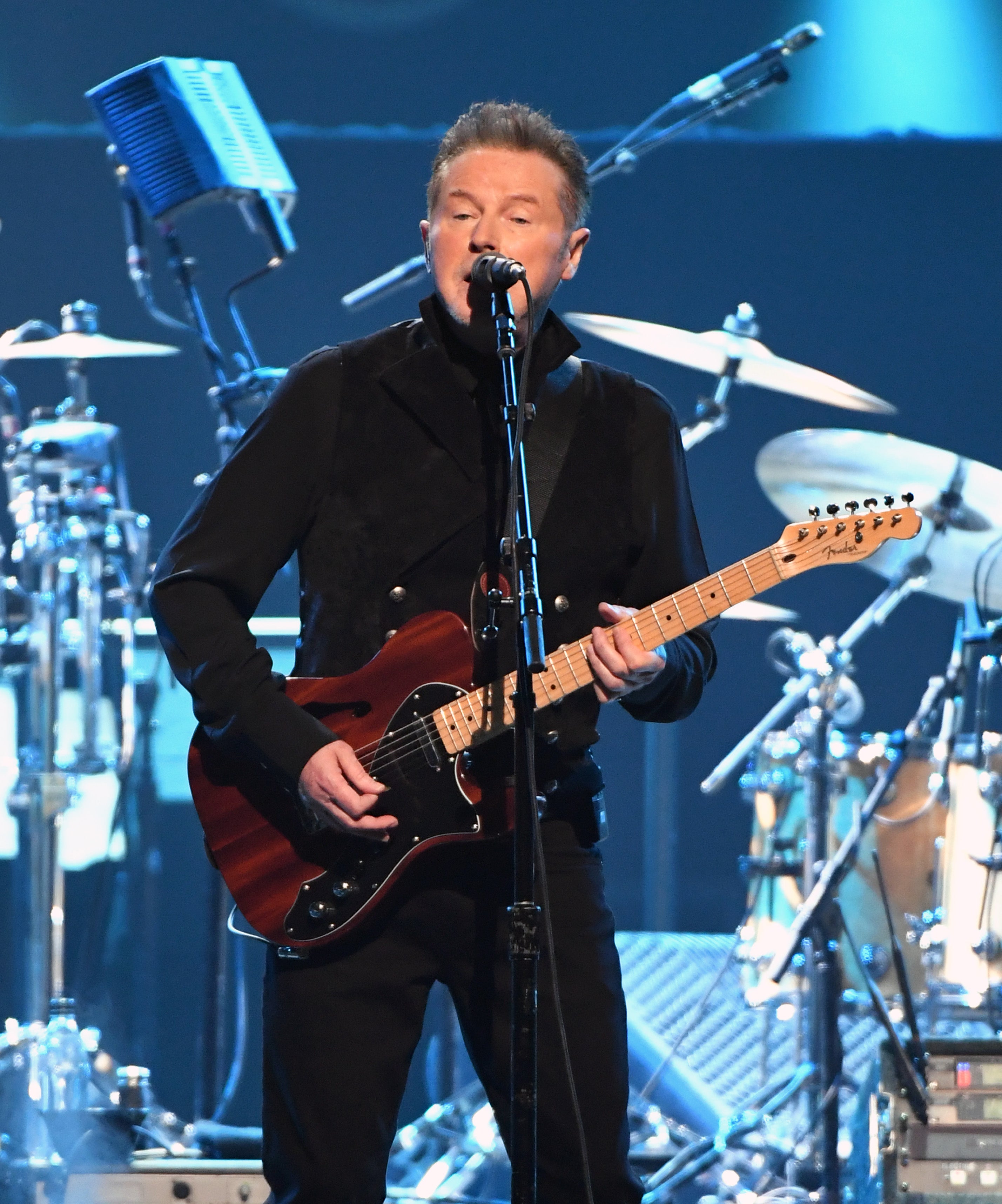

For Henley, “The Boys of Summer” remains a landmark achievement – not just musically but also as an encapsulation of his view of life and the passage of time. His perspective is that the years fly by. That we have to make the most of what time we have. And that looking back can cause more harm than good. “The song is almost 40 years old now,” he commented. “It’s just another reminder that life is short, but it’s very wide.”

Henley is 77 now and has done a lot of living since “The Boys of Summer”. But 40 years on, it’s clear that the song has lost neither its potency nor its poignancy. It’s a meditation on nostalgia that – fittingly – only seems to get better with time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks