David Crosby: ‘America thinking we have a right to go and stick our nose in is absolutely wrong. It’s bulls***’

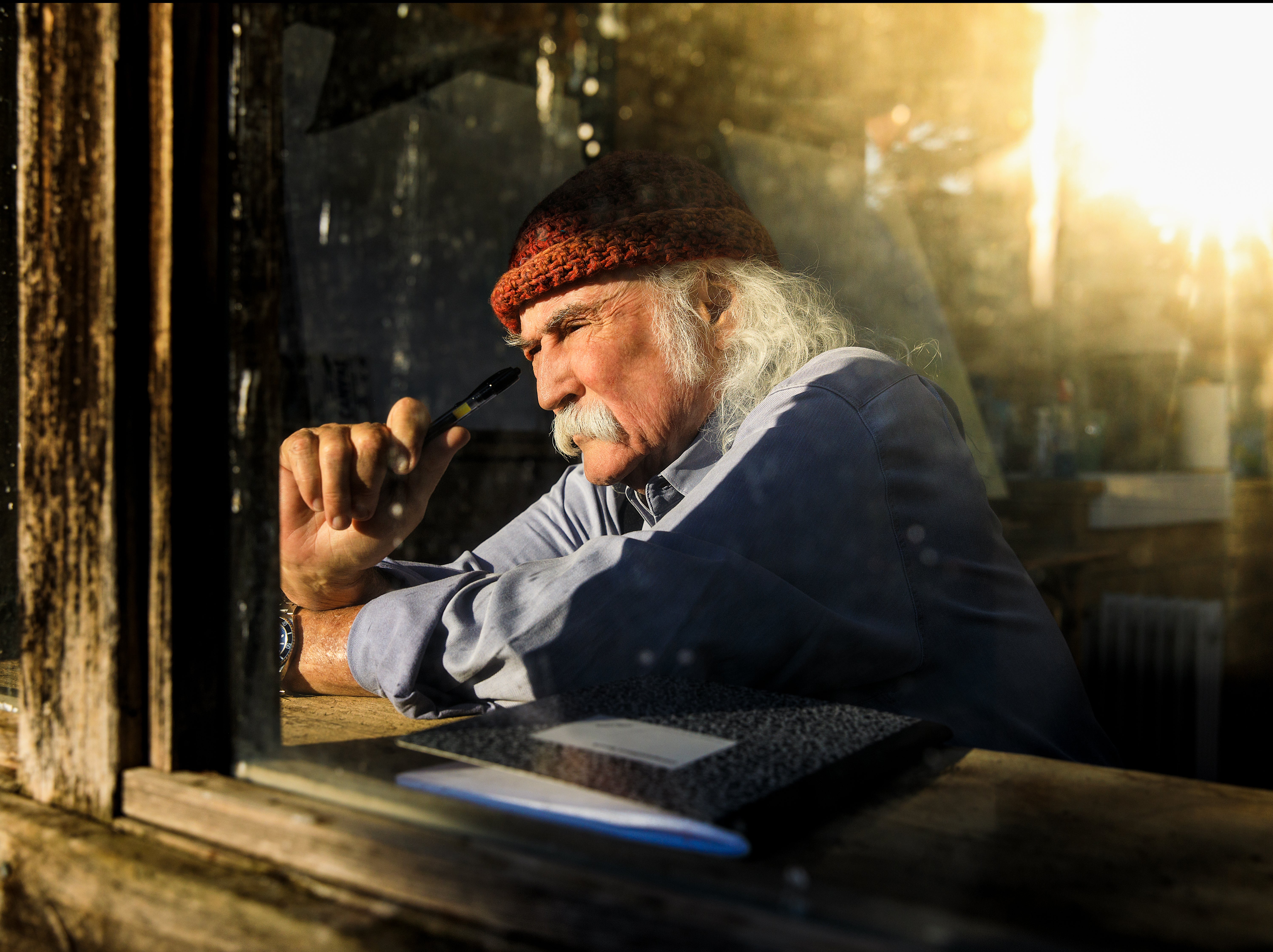

At 80, the folk-rock icon has just released his eighth solo record. He talks to Kevin E G Perry about the US exit from Afghanistan, corporate greed, the song his son wrote that made him cry and why he still won’t cut his hair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Crosby is an easy man to share your secrets with. Maybe it’s because of the life he’s lived, surviving three heart attacks, nine months in a Texan prison for drugs and weapons offences, and five decades of fractious folk-rock stardom as a member of first The Byrds and later supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. Maybe he just has that kind of face, a wizened version of Yosemite Sam, as former girlfriend Joni Mitchell once described him. Either way, people have a habit of opening up to him. Take the soldier he met in an airport bar not too long ago, just back from Iraq and Afghanistan. He started telling Crosby about a firefight he’d been in, how in the middle of it he’d fired off this shot with an assault rifle that flattened a guy from 200 yards, maybe the best shot he’d ever taken. Afterwards, when the fighting was over, he went over to find the body. He’d killed a 12-year-old boy.

“He looked at me, when he said that, and his eyes were…” Crosby trails off, trying to find the words. “He was in hell,” he says finally, his clear, melodic Californian tones growing softer. “He was absolutely torturing himself to pieces right there in front of me, drunk and shattered. Listen, if you’d seen it, man, it would have broke your heart. The guy didn’t mean to do anything wrong. He was just a regular guy doing his job and he was destroyed by it.”

Crosby was so moved by the chance encounter that he wrote a song about it, “Shot at Me”, a searingly poignant ballad that appears on his new album For Free. It is Crosby’s eighth solo record, five of which have arrived since 2014, when he was 72, representing a remarkable late-career renaissance. Today, he’s speaking over the phone from the ranch house in Santa Ynez, California that he shares with his wife of 34 years, Jan Dance, and their various dogs and horses. A week ago he celebrated his 80th birthday there, with a homemade chocolate cake and a little reluctance. “I’m not sure 80 is one you celebrate,” says Crosby with amusement. “It’s one you kind of go: ‘Oh, Jesus!’”

Becoming an octogenarian has clearly done nothing to dim Crosby’s sense of political outrage. We’re speaking as America withdraws its last troops from Afghanistan, and Crosby remains adamant that they should never have been there in the first place. “America thinking that we have a right to go and stick our nose in, in Vietnam and in the Middle East and in the other places that we’ve done it, is just absolutely wrong. It’s bulls***,” says Crosby, growing increasingly animated as he points his finger squarely at the corporations who profit from America’s perpetual war machine. “It’s the companies that make the tools of war that influence our politicians into getting us into more wars so that they can buy more hardware and spend another couple of TRILLION dollars. That money could have saved lives, educated children, built homes, fixed bridges… everything that we need to do here in the United States. No. Those companies got us to spend money on bombers instead.”

Crosby, a key voice in the hippie counter-cultural movement of the 1960s, has been railing against the corporate takeover of American life for more than 50 years. In 1969, just hours after playing Woodstock, he appeared alongside Stephen Stills, Joni Mitchell and Jefferson Airplane on primetime chat show The Dick Cavett Show. At one point, Cavett asked the assembled musicians whether any of them had anything they’d always wanted to say on television, and it was Crosby who piped up. “The air that we’re breathing is not clean, right?” he asked, to general agreement. “Consider this: the only way to solve it seems to be to convince GM, Ford, Chrysler, 76, Union, Chevy, Shell and Standard to go out of business.” A slow-building round of applause filled the studio, before Crosby admitted how unlikely this would be: “Which is merely a set-up for the punchline, which is: ‘Fat chance!’”

Half a century on, with the evidence of environmental collapse all around us, Crosby takes little solace in knowing he made a prescient point. “We’re up against greed,” he says. “These companies keep us running on oil and coal because they’re selling us the oil and the coal. They don’t care what the right and wrong of it is.” America in 2021, he says, is even worse off than he would have predicted back in 1969. “I thought we would manage to get people to do the intelligent thing, the right thing,” he says, adding that the response to the Covid pandemic has made him doubt his country’s ability to come together to deal with the changing climate. “We have so many people that are so dumb, they think the government’s trying to steal their kidneys,” he says. “It’s f***ing dumb as a post.”

Crosby has long been known for being outspoken. Indeed, he was sacked from his first band The Byrds in 1967, in part because he’d used their performance at the Monterey Pop Festival to make lengthy speeches between songs about topics including the assassination of John F Kennedy and his desire to give LSD to “all the statesmen and politicians in the world”.

Crosby, undeterred, embraced his status as a figurehead for the hippie movement. Among his contributions to Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s 1970 album Déjà Vu was “Almost Cut My Hair”, a definitive portrayal of the conflict between the establishment and the counter-culture represented by long-haired hippies. “We were trying to differentiate ourselves from the previous generation,” says Crosby. “It was a simple visual clue that we were different, and we liked that. I still like having my hair long, for two reasons. Because I think it looks better that way, but I also like it because it does say: ‘Hey, I’m a hippie, and I believe certain things.’ And yes, I do. I think love is better than war. You can convict me of that one.”

It was during the recording of Déjà Vu that Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton was killed in a car accident, on 30 September 1969. Her death devastated Crosby, who sought out oblivion in freebase cocaine and heroin. His junkie years came to an end in 1985, after he was convicted in 1983 of possessing a .45-caliber handgun and cocaine. He served nine months in a Texas state prison, which did at least force him to get clean. Still, his health was shot. Hepatitis C had ravaged his liver, and by 1994, he was told he needed a transplant.

While being treated at the UCLA Medical Centre, Crosby met someone who would go on to be a central figure in his later life: his son, James Raymond. Raymond had been born in 1962, but his birth mother put him up for adoption and Crosby had no way to contact him. Raymond was already 31 and an established session musician by the time he learned the identity of his biological father. “He found out it was me, which he didn't really believe at first!” says Crosby, with a chuckle. “We met up at UCLA, and normally those meet-ups go badly. One or the other brings too much anger, too much pain. He didn't do that. He gave me a clean slate, and let me earn my way into his life. We became very, very close, and that’s a f***ing gift of gigantic proportions, man. It’s f***ing wonderful.”

Raymond went on to produce three of the five albums Crosby has released since his 2014 comeback Croz, including For Free. He also wrote the new record’s staggering closing track, “I Won’t Stay for Long”, a reckoning with mortality rendered even more heart-wrenching by the knowledge it was written by a son for his father to sing. “I cried when I sang it, man,” says Crosby, softly. “I don't know what to tell you. The joy in the situation is me being able to look at my son and know that he is at least as good a writer as I am, if not better. That song is unquestionably the best song on the record, and it’s a record full of good songs!”

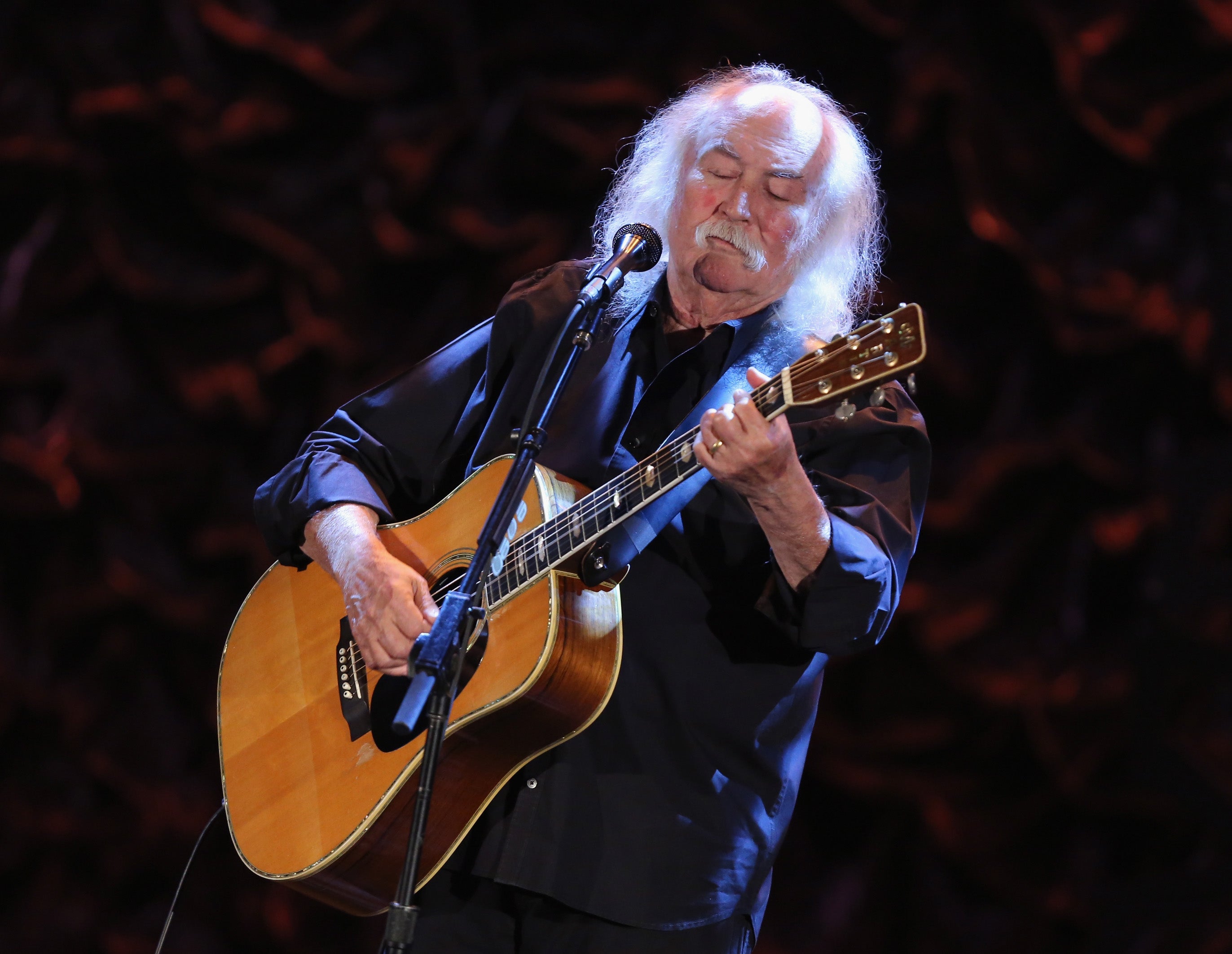

They’re good songs, though, that Crosby fears he’ll never perform live. When we discuss the possibility of his returning to touring, a deep melancholy enters his voice and for a moment Crosby the raconteur disappears completely, his answers turning monosyllabic. Do you think you’re going to be able to tour this record? “No.” Do you think you think touring is over for you? “Yes.” How do you feel about that? “Sad.”

In March this year, having realised that the pandemic would prevent him hitting the road, Crosby came to the painful decision to sell the recorded music and publishing rights to his entire catalogue to Irving Azoff’s Iconic Artists Group. “It was awful, man,” he says. “It's not what I wanted to do. I had two ways of making money, records and touring. Records they don't pay us for any more. Streaming doesn’t pay us, and they're making billions – with a ‘B’ – of dollars. That ain’t right. Then along comes Covid and I can’t tour, so that’s why I had to sell the publishing. I didn’t have any goddamn choice.”

He doesn’t quite rule out the idea that he may be able to return to the stage for a few final farewell performances, although he has serious doubts. “You never say never,” he says. “But I’m 80 years old now. I don't have a lot of stamina and my hands are going from tendinitis, so I don't see me getting out there again. I don't like that at all. I love playing live, man. I’m good at it, and I love it. I’m sure I’m gonna miss it every day for the rest of my life.”

These days, Crosby gets his fix of social interaction through Twitter, where he rates how well his fans have rolled their joints. His unfiltered tweets still have the capacity to get him into almost as much trouble as proselytising about LSD from the stage used to. A prime example was the row that erupted earlier this year after fellow singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers smashed her guitar on Saturday Night Live, and a Twitter user asked Crosby what he thought about it. “Pathetic”, he tweeted, which provoked the personal response “little bitch” from Bridgers. Crosby added: “Guitars are for playing... making music... not stupidly bashing them on a fake monitor for childish stage drama... I really do NOT give a flying F if others have done it before It’s still STUPID.” But we don’t get into that today. His thoughts on the social media platform are wholly positive. “I think people are absolutely fascinating, man,” he says. “You can actually talk to people on Twitter, which is great. I also like that the ones who are trying to start a fight with you, the trolls, you can just delete them and move on. I have a couple of hundred thousand people that are interested, and we talk, and it’s fun.”

Even if his touring days are now behind him, Crosby still believes he has great music left in him. He says that he and Raymond are already two songs into writing their next record together, while he’s also booking studio time for another new album with the band he first put together for 2016’s Lighthouse. Incredibly, his productivity is at an all-time high.

I think music is a lifting force

“That's kind of amazing,” says Crosby, the soulful warmth back in his voice. “But there it is. I figure this, man: if my voice is gonna be good, and I’m gonna be happy, and I’m still able to get up and walk to a microphone…” He pauses for just a moment, as if picturing himself back in the studio. “This is gonna sound a little cosmic and hippie,” he says eventually, “But I think music is a lifting force. I think it makes things better and it makes people happy, and I love being able to contribute to that. That’s a good purpose for me in my life. I don't know how to do anything but that. That works for me.”

‘For Free’ by David Crosby is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments