Cocaine, no sleep and deep soul: The story of David Bowie’s Young Americans

‘His eyes didn’t look healthy but his voice might be better than on any other album’ – pianist Mike Garson and guitarist Carlos Alomar recall the sessions that featured soul greats like Luther Vandross and visitors John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen. By Mark Beaumont

It wasn’t just the alien eyes, the golden disc embedded in his forehead or the shock of Martian mullet – the creature known as Ziggy Stardust had a strange pulse too, a vibration in his veins that no earthly drug could have given him. Pianist Mike Garson, drawn from the jazz world to bring jagged avant-garde shapes to 1973’s Aladdin Sane, saw it in him as they travelled together on Ziggy’s farewell tour, gazing out at America through tinted glass with a mixture of awe, infatuation and hunger. Ziggy’s bloodstream, he saw, was sucking in soul.

“I remember driving in the limos with him at that period of time and he’d have the headphones on listening to Aretha Franklin,” Garson says today. “He was already sucked into that universe. He told me that when he grew up in the Fifties and Sixties in London, he loved those black soul groups. He loved Little Richard, he thought he was a god. It was absolutely in him, like you can’t believe. He was consumed by that music. You see him in the limo listening, and you could see it going in his body, the feel of ‘Natural Woman’ by Aretha. It was like he was being infused.”

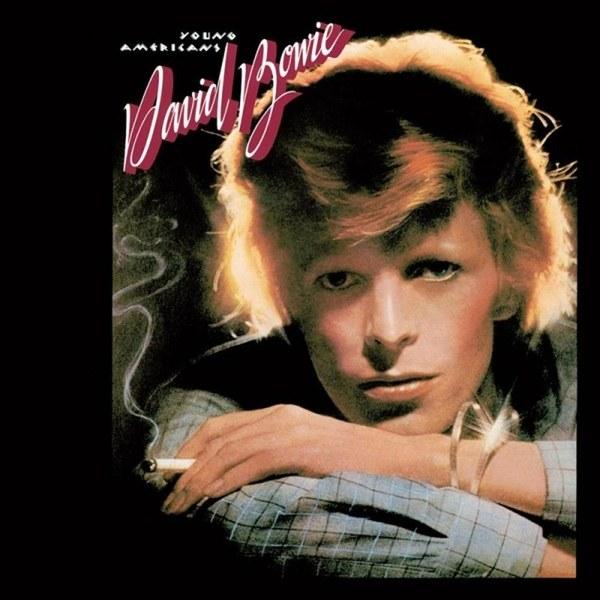

Within two years of Ziggy’s onstage demise at the Hammersmith Apollo in July 1973, David Bowie’s deep soul infusions would culminate in Young Americans, his legendary “plastic soul” record released 45 years ago next month (7 March). Those rock historians who dismiss the album as a white elephant among Bowie’s 1970s output, a throwaway transition record between the sci-fi glam years and the Thin White Duke era of Station to Station, underestimate its significance. Because this was Bowie’s first display of true fearlessness, rock’s most celebrated shape-shifter attempting his first real post-fame metamorphosis.

Before Ziggy stole the world, Bowie was, in essence, following his nose. From his solo beginnings as a macabre Anthony Newley with 1967’s self-titled debut album he chased the psychedelic rainbow on 1969’s Space Oddity, embraced White Album-like rock tones on The Man Who Sold the World (1970) and perfected the art of early 1970s folk pop on 1971 masterpiece Hunky Dory. He did all this in relative obscurity, as if trying on an entire costume box of musical roles in the hope that one might capture the wider imagination. When his space-age take on glam rock, 1972’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, did just that, hitting the UK Top 5, it launched a passionate and exotic cult of Ziggy. It strived to be both gender- and, indeed, species-fluid, and Bowie followed it up with two albums which merely presented different shades of Stardust. The shifts in image with each record were bold and brazen – lightning bolt face-paint for 1973’s Aladdin Sane and a weird Minotaur dog look for the following year’s Diamond Dogs – but the music itself, besides introducing some avant garde touches, strayed little from Ziggy’s glam rock lane.

Young Americans (1975), then, was the first time that Bowie showed the true artistic bravery that would come to define his career, risking it all to follow his heart into soul. “It was in our upbringing,” producer Tony Visconti – who had reunited with Bowie to mix Diamond Dogs having produced his first three solo albums – told Uncut. “We heard music like this when we were babies. Regardless of what race you were, you were exposed to this beautiful music when you were young.”

Garson believes that touring America helped make Bowie’s soul-itch impossible to ignore. “He took America in his stride but was also consumed by it. How could you not be? Here’s a guy coming from England and they’re looking at artists like the Ray Charleses and Arethas and these great geniuses of black music and soul music. He wanted a taste of it.”

And Bowie wanted that taste to be as authentic as possible. Over the course of the first leg of his grand, theatrical Diamond Dogs tour in 1974, he began recruiting musicians steeped in the history of funk and soul to work with on his next album. He would record it at Sigma Sound studios in Philadelphia, the epicentre of Philly soul, and his first thought was to approach the house band MSFB, who had epitomised the style he loved with their 1974 hit “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)”. “It was a very smart move,” Visconti said. “If you wanted to make an authentic R&B album you would make it in an American studio with American musicians.”

When all but MSFB’s congo player proved unavailable, he turned instead to a New York guitarist he’d bonded with while producing tracks for Lulu; one Carlos Alomar, alumnus of James Brown’s Sixties band and regular on the Chitlin’ Circuit. “Everything started at the Lulu sessions,” Alomar says today. “I invited him to come to my house because he was just 98 pounds and I’m talking about very translucent white skin, so he just looked like ‘you need a home-cooked meal’. One day I heard the intercom and it was Bowie’s bodyguard saying ‘Mr Bowie is here to see Mr Alomar.’ Robin [Clark, Young Americans’ backing singer] and I and he had a great meal. We talked about everything. He was very interested in the Chitlin’ Circuit, the Apollo Theatre, Harlem and all that. We actually took him to the Apollo where I was playing with The Main Ingredient [fronted by Cuba Gooding Sr] and introduced him to Richard Pryor, who was hanging out.

“You have to remember that the Brits studied R&B music. When I first met Bowie… he had a case that was loaded with Thelonious Monk, all of the jazz greats – him being a saxophone player – R&B from Stax, he had his historical relevance at that time. There’s no doubt in my mind that he was primed and ready to go when it came to implementing soul music into his music.”

Alomar and his wife, Robin Clark, would become instrumental in forging the sound of the album. They introduced him to their good friend Luther Vandross who, after impressing Bowie at an initial session, called in members of his own band to join Garson, Willie Weeks (bass) and Andy Newmark (drums) at Sigma Sound shortly after the first leg of the Diamond Dogs tour finished in August 1974.

“Philadelphia and Sigma Sound were the home of so many of those great groups like The O’Jays,” says Garson, who relished playing with American musicians from the jazz, R&B and classic soul traditions. “You go into that studio, you get a different series of notes than you get in London. [Bowie] told me it was gonna be very different and I wouldn’t be playing like I played on Aladdin Sane, I’d be playing in that style like those records.”

Characteristically for Bowie, what took place at Sigma Sound was total soul immersion. He took on a brand new persona, The Gouster – a hip American soulboy in baggy slacks and red braces – and the phrase became the album’s working title (and the title of a “lost” pure soul album that would emerge from out-takes of the session in 2016). “It wasn’t so much a concept as a way of setting the tone that we were going to make a very hip album,” said Visconti.

The sessions themselves were a breakneck culture mash. In order to fully absorb the authentic soul influence, Bowie encouraged the musicians to jam, out of which he’d build his own, slightly askew breed of soul melody. “Us musicians were left to our own devices,” says Alomar. “When you are the artist and you’re lending yourself to a new platform, you certainly don’t have the goods to be able to tell them what to do. If he had got ‘TSOP’… what the hell is David Bowie gonna tell them to play? He couldn’t tell them jack, OK? If you want to get to some place, you have to be curious and courageous. You cannot try to control something if you don’t know what it is. Otherwise you can stay a Spider from Mars.

“Look at the videos. He’s reserved, he’s listening, he’s somewhat pensive… it’s a somewhat more controlled, calculating David Bowie not trying to mess anything up once he got his hands on it.”

The work rate of musicians used to laying down tracks in an afternoon, combined with Bowie’s increasing cocaine use making sleep seem for the weak, turned the sessions into round-the-clock affairs, with the band living virtually full-time in the studio. “It felt that way because of the oddity of the hours and the way that we were called to task,” says Alomar. “If he was inspired to hear a certain melody, he would stop the session and say, ‘give me a moment, I want to put these ideas down.’ The room would clear, he would go into the booth, he would lay down some ideas, and then after those ideas happen we would be called back in to continue what we were doing. If it happened to take eight hours for him to make that idea happen then we would wake up out of our little sleep and then we carry on. Two o’clock in the morning, OK, rise and shine!”

“Sometimes everyone would fall asleep and it’d be me and him and Tony Visconti at three in the morning just starting,” says Garson. “I loved it, because it’s perfect David Bowie.”

“We were primed and ready to go so it didn’t matter,” says Alomar. “When you have session musicians of this calibre it doesn’t really matter when you call them. Like, I don’t jam? Dude, I was doing after-hours joints starting at two o’clock in the morning. It’s our lifestyle that he had to deal with, not us dealing with his lifestyle.”

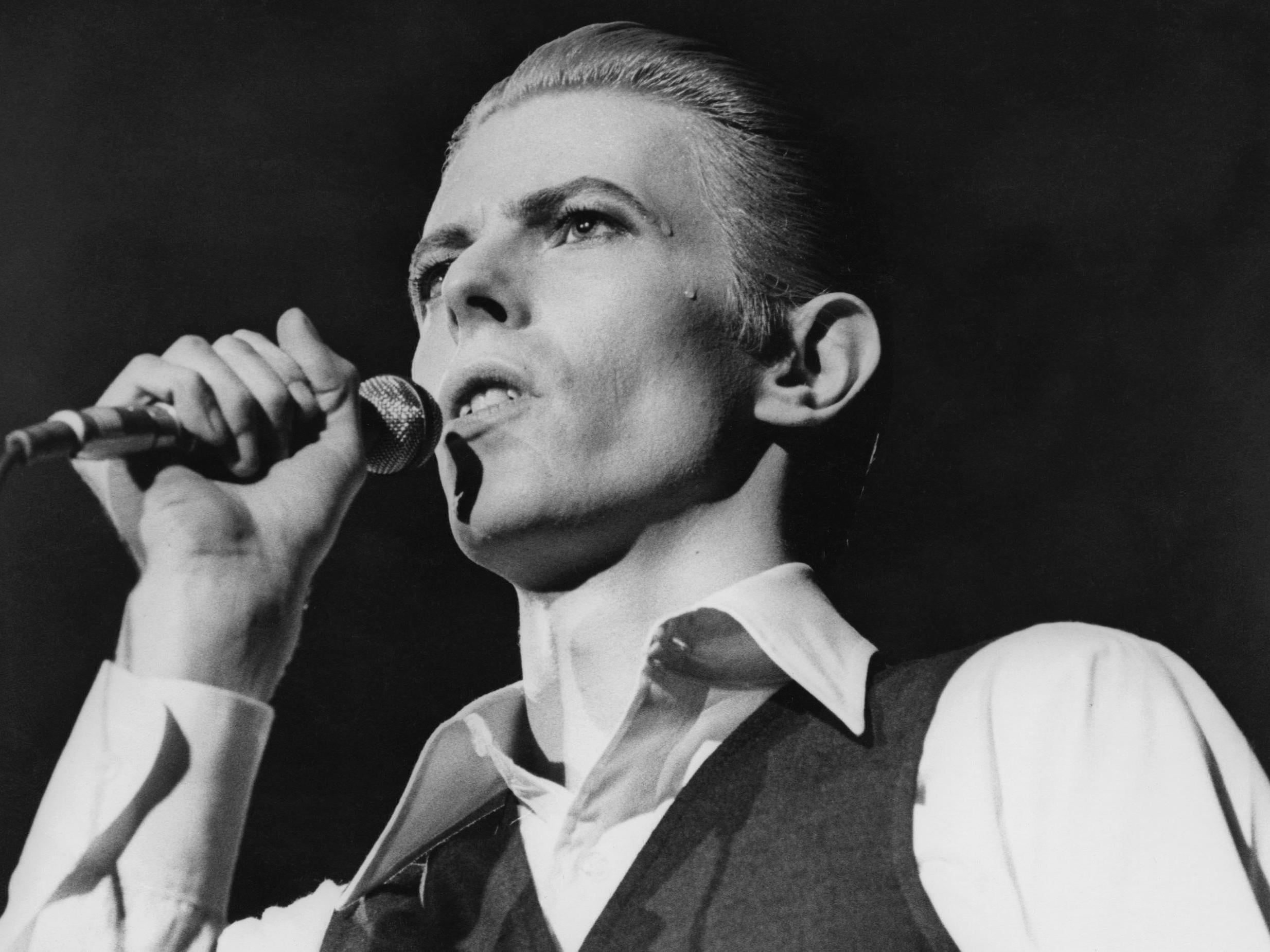

Within a year of recording Young Americans, Bowie would be holed up, hermit-like, in an LA apartment concocting the follow-up while engrossed in books about protecting yourself from paranormal malevolence and living entirely on a diet of fine-grade cocaine, milk, red peppers and Marlboro. As early as the Young American sessions Garson remembers “he didn’t look too good. He looked too thin, his eyes didn’t look healthy. The strangest thing is it didn’t seem to affect his creativity or his singing. His voice on that album might be better than on any other album.”

Alomar remembers drugs “fuelling” the Young American sessions rather than “depleting” them. “You realise you’re talking to New York City session musicians, right?” he laughs. “He doesn’t sleep, he drinks milk, he’s just trying to keep up, the demands of having professional session musicians knocking stuff out in the soul music vein that you so wanted created a dilemma in him that meant he had to rise to the challenge, and immediately. It’s really wonderful that he did have a proper rearing in soul music, because what came out of his mouth was a proper interpretation of what soul music is.”

Was he confident or unsure of his soul abilities? “David Bowie has never been apologetic, scared, reluctant or ambiguous about his ability to morph and change and go in at full steam,” says Alomar. “Burn the bridge after you cross it – this way you don’t have to worry about that change because there’s no going back to what you were. I liked the fact that he knew how to kill himself and, like a phoenix, come out as something else.”

Bowie did, however, seek outside approval for what he was doing. When he attempted to record a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City”, he invited Springsteen himself to stop by and hear it. ‘He was very shy,” Bowie wrote later. “I remember sitting in the corridor with him, talking about his lifestyle, which was a very Dylanesque – you know, moving from town to town with a guitar on his back … He didn’t like what we were doing, I remember that. At least, he didn’t express much enthusiasm. I guess he must have thought it was all kind of odd. I was in another universe at the time.”

More positive were the Sigma Kids, a band of Bowie fanatics who had camped outside the studio in rain or shine from the moment the band arrived, and were rewarded with an in-studio preview playback at the end of the sessions. “We had been hanging out around the studio for roughly two weeks,” Sigma Kid Patti Brett told Esquire in 2016. “One night when he arrived at the studio he said that if we were there when he came out he’d have a surprise for us. He told us it was unlike anything else he’d done and that he really wanted to get some feedback. They played [the album] for us, and you could tell he was nervous. But at the end someone shouted, ‘Play it again!’ And he got this huge grin on his face and said, ‘Really?’ And everyone screamed, ‘Yes!!’ And he played it again, and that started the party.”

Alomar remembers that moment: “When they asked to hear it again, David became extremely fluid, mixing with them, talking with them, chatting them up, smiling, laughing. If he knew how to high five at that time, he probably would have done it.”

“It was a beautiful moment,” Garson recalls. “It showed a part of him that had a lot of humility… Because this was such new territory for him I guess he didn’t want to feel like a poser or fake.”

The album was indeed a cause for celebration. The title track might have documented the long, lonely aftermath of a hasty young marriage, but its brazen bounce seemed to mark a new era of cross-pollination between British and American youth culture, with its Philly sax breaks and its sly soul winks to The Beatles’ “A Day in the Life”. “Win” and “Right” were faithful tributes to classic boudoir soul and jazz-fusion given a light brushing of Abbey Road guitar; “Fascination”, originating from an earlier Vandross song, was a sparse funk-out where sci-fi glam met an earthy groove. If tracks like “Can You Hear Me” were Bowie’s blue (and brown) eyed soul moments, their gaze was lowered in honour of Marvin, Aretha and the soul greats.

So swept up was Bowie in his new direction, and his fans’ response to it, that he launched it immediately. The cumbersome and expensive sets of the Diamond Dogs tour were ditched halfway through – by its third leg it was renamed The Soul Tour, stripped of all of its theatrics and peopled by Bowie’s new soul associates.

There was, however, one more great Bowie wanted to lure onto the record. With sessions wrapped up at Sigma Sound and Visconti already flown home, Bowie hit New York’s Electric Lady Studios in January 1975 with an altered line-up of musicians, recording a cover of The Beatles’ “Across the Universe” in order to tempt his friend John Lennon to the studio to hear it. The ruse worked.

Alomar recalls working on a funk riff scavenged from a previous song called “Foot Stomping” before Lennon showed up. “Taking from my past history of working with James Brown, I decided to approach it like that. I’d thought of putting some licks down and by that time David had showed up with John Lennon and May Pang, who he was seeing at the time. He listened to it, ‘that’s cool’. ‘You wanna play?’ ‘Sure’. He had an acoustic guitar so he strummed a little acoustic here and there.”

“God, that session was fast,” Bowie said of Lennon’s visit in 1983. “That was an evening’s work! While John and Carlos Alomar were sketching out the guitar stuff in the studio, I was starting to work out the lyric in the control room. I was so excited about John, and he loved working with my band because they were playing old soul tracks and Stax things. John was so up, had so much energy; it must have been so exciting to always be around him.”

“I was invited to go out to dinner with them,” Carlos laughs. “Who would say no to that? Well, Carlos Alomar said no to that because I was hearing these guitar parts in my head and I was not about to go and have dinner with David Bowie and John Lennon and be all goo-goo ga-ga and forget my parts. I reluctantly said no and stayed in the studio. To my delight, when David Bowie returned and heard all of the parts I had laid down he basically said, ‘the song is done, I’d like to put down this one little guitar part.’”

Bowie remembered that he and Lennon “spent endless hours talking about fame, and what it’s like not having a life of your own anymore. How much you want to be known before you are, and then when you are, how much you want the reverse: ‘I don’t want to do these interviews! I don’t want to have these photographs taken!’ We wondered how that slow change takes place, and why it isn’t everything it should have been.”

As Alomar notes, the resulting song “Fame” was far darker and more blues-based than the rest of Young Americans – a sign, perhaps, that his Philly experience had got soul music out of Bowie’s system?

“Absolutely not,” Alomar states. “If you listen to the next album Station to Station, which they say is such an experimental album, well that’s a crock of crap, OK? The only thing experimental on there is two songs – ‘Stay’ and ‘Station to Station’. Everything else is R&B.”

Garson agrees, though, that by the end of the Soul Tour Bowie was ready to regenerate his stylistic persona again. “He went through things fast. It’s like a person living 10 lifetimes in three years. He was always a few steps ahead of us. When I’d be on these tours, I knew when he was done because then he would sort of just phone it in. They were still great but in his head he was on the next project. And the next one and the next one.”

And the true importance of Young Americans? “I think because he was uncertain if he was good at it, he demeaned himself by calling it plastic soul,” Garson argues. “It was much deeper than that, I felt. He owned that music and he did his take on it. It wasn’t fake, it was just unusual.”

Alomar, meanwhile, sees it as a totem of fearless reinvention. “Many artists stay within a genre and when that genre dies so does their career. But everybody’s lifetime has a different David Bowie. You can switch from one to another and there’ll be two or three albums that can exemplify it perfectly. Should you go to the next album, you lost that David Bowie. He drags you kicking and screaming into the future – let go or be dragged.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks