David Bowie: How the outsider's outsider proved himself far braver than the rock’n’roll mainstream

That the singer confronted his own mortality in graceful privacy and a ferment of creative vitality is quite remarkable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He may have steadfastly refused offers of honours, but the way in which David Bowie confronted his own mortality confirmed the true nobility of this most vital cultural icon.

The cliche of his apparent “battle with cancer” was quickly invoked, but as those afflicted know, cancer is less a battle than a simple matter of endurance, a war of attrition in which there is ultimately only one victor. That Bowie was able to face its gradual etiolation, not just in graceful privacy, but in a ferment of creative vitality, is quite remarkable. His recent Blackstar album, released last week, is as sonically challenging as any in his wide-ranging catalogue – the dark, brooding mysteries of its seven songs characteristically offering no quick or easy way in.

But this is exactly what Bowie has done all his career, and it is one of the main reasons his fans have remained so faithful. For many, he was the first one to challenge them, the pop star who dared ask difficult questions about identity and art. And not simply in terms of fashion, although his ever-changing look was an obvious source of immediate appeal. “The trousers may change,” he once said, “but the actual words and subjects I’ve always chosen to work with are things to do with isolation, abandonment, fear and anxiety – all the high points of one’s life.”

The wry, sardonic twist disguises the essential truth of the claim: for where pop music endemically desires and encourages a cheery mass response, and seeks out the security of a collective experience, Bowie’s genius, like that of Dylan before him, was to find that sort of resonance in the more uncomfortable, individual corners of life. He was the outsider’s outsider, the original avenging nerd, the five-stone weakling who fought back against sand-kicking bullies and proved himself far braver than the burly rock’n’roll mainstream.

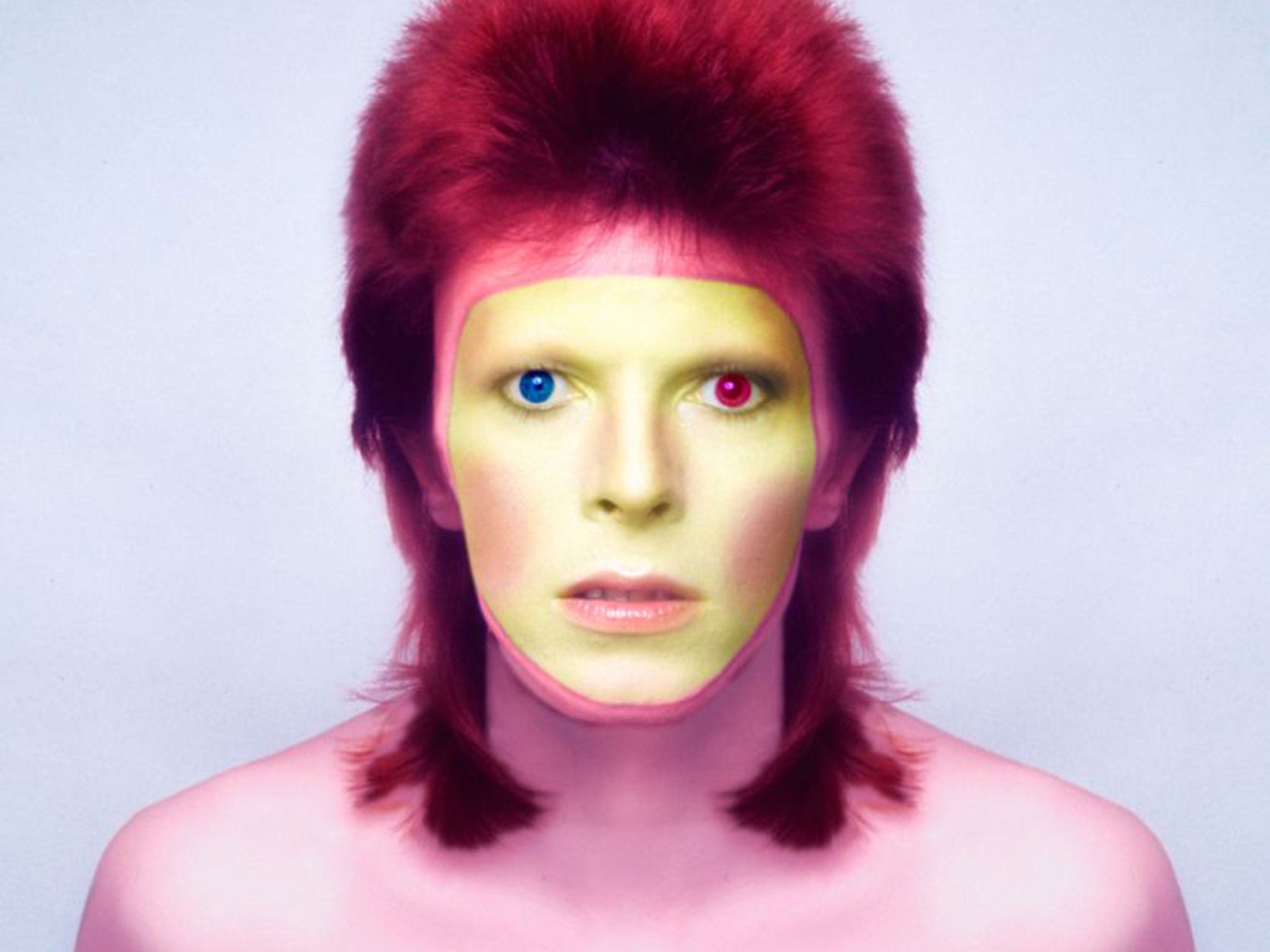

And not just aesthetically. It’s impossible, at this remove, to adequately convey just how courageously unthinkable Bowie’s brazenly brandished bisexuality was in the early Seventies, when his performance of “Starman” on Top Of The Pops shocked a nation and brought the pop world, as it were, to its knees. That was a time when the gaudy flamboyance of psychedelia and the Swinging Sixties had given way to a lumpen uniform of blue denim and ex-army greatcoats in shades of grey; and the musical landscape had become similarly grey and grimly rebarbative.

Bowie offered a light of possibility that illuminated a generation; and although the resultant trend of glam-rock offered a platform for tinfoil paedophiles as well as questing explorers, its adherents were emboldened to value and pursue their own uniqueness, rather than hide it. The result was a legion of inspired individuals and entire pop movements: without Bowie, there would be no Boy George, no Joy Division, no Siouxsie, no Marc Almond, no Madonna, no New Romantics, no Electropop – to name but a few. Scratch most punks, and you’d find a rebellious Bowie fan on the make.

It’s no surprise that he was virtually alone in surviving punk’s scorched-earth immolation of earlier pop and rock, an auto-da-fé he avoided partly through his nimble cultural manoeuvring. This has been a feature of Bowie’s modus operandi ever since he first abandoned his attempt to become a hipper version of Lionel Bart in favour of the psychedelic space-folkie that secured his breakthrough hit with “Space Oddity”, now such a cultural touchstone it’s sung by orbiting astronauts in space stations. Listened to again more than four decades later, it’s striking how similar in mood and tone that song is to certain tracks from Blackstar. Isolation, abandonment, fear and anxiety – “all the high points of one’s life” – are copiously evident in both, a measure of the consistency of Bowie’s concerns throughout all the twists and turns of his career.

Initially, however, his cultural manoeuvring proved almost terminally disastrous, as, perhaps influenced by the success of such bands as Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, the follow-up album The Man Who Sold The World took a sharp left turn into heavy rock and themes of madness, paranoia and murder. Its heady cocktail of influences such as Kafka and Ballard effectively laid the groundwork for Goth and new wave, and proved crucial in the artistic development of both Ian Curtis and Kurt Cobain. Hunky Dory, his first landmark album, saw him experiment with constant musical change and the adoption of characters.

The first and most enduringly famous of these, of course, was the titular star of The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, which catapulted Bowie from cult hero to global phenomenon. Once again, he used a sci-fi theme - a pop star of the end times viewing himself as a vessel for alien saviours - but this time, in support of an apocalyptic message of nihilist decadence that would linger through several subsequent works such as Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs, as Bowie himself plunged deeper into drug addiction and paranoia. But he had developed a genius – perhaps learned from Lou Reed whilst resuscitating the former Velvet Underground frontman’s career by producing his Transformer comeback album – for welding together dark themes and sunny pop in songs like “Starman” and “All The Young Dudes”. The former is a delusional hymn to salvation with more than a sliver of “Somewhere Over The Rainbow” about it; the latter, gifted to Mott The Hoople, is likewise commonly perceived as an anthemic celebration of youth, when it’s actually about the erosion of youthful hope and volition.

Indeed, for one so infused with creative vitality, Bowie’s work through the mid-Seventies was marked by a pessimistic attitude that doubtless reflected his literary leanings to dystopian texts like Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, all notable inspirations behind the lacklustre Diamond Dogs album.

But as he became more exposed to contemporary America through touring, Bowie sloughed off his predominantly British, predominantly Sixties musical influences and became deeply enamoured of black R&B, which he transmuted into what he termed the “plastic soul” of Young Americans. Its febrile, itchy funk grooves proved surprisingly popular in America, where the co-written duet with John Lennon, “Fame”, would furnish the first of Bowie’s two stateside number ones; but as soon as it was finished, he was off elsewhere again, building a bridge back to Europe with Station To Station. Released in 1976, it’s one of his most enduring and significant albums, despite being effectively a transitional work. Recorded following his starring role as the stranded alien of The Man Who Fell To Earth, it forges a super-strong alloy of funk and krautrock, with the influence of the motorik grooves of German band Neu! especially notable in tracks like “TVC 15” and “Stay”.

Bowie, by now, was at the epicentre of cultural life, working at the cutting-edge of music and film, and fulfilling a punishing concert schedule as his latest character the Thin White Duke. Fuelled by a colossal intake of cocaine and a deepening fascination with occultism and the Kabbalah, he was heading full-speed towards the buffers. The inevitable crash came during his 1976 Tour, when he – or rather, the Thin White Duke – started spouting ill-judged comments about the benefits of fascism, which he would later blame on his addiction and the influence of his stage character.

Pilloried in the music press, he retreated to Berlin to work with Brian Eno on the Low album, yet another landmark work which anticipated future electronica, new wave and post-rock developments through its amalgam of synthesiser music, krautrock and ironic pop. Recorded whilst he was attempting to kick the cocaine habit, its title refers to both his temperament at the time – powerfully evoked by the melancholy mood music of the second side – and to the low profile he was keeping. It was the first of what would become his “Berlin Trilogy”, its formula and style continued on Heroes and Lodger.

For many, the Berlin Trilogy remains the high-water-mark of Bowie’s output, the defining musical statement of his career. Certainly, it was a hard act to follow, and although his early-Eighties releases included some of his most successful singles, such as “Ashes To Ashes”, “Fashion” and “Let’s Dance”, there seemed to be a diminution in his creative potency - these hits were rather like perfunctory retreads of former glories, in thrall to the new studio technology of machine beats and sequenced grooves. Though it furnished the hits he desired, Let’s Dance presaged a downturn in Bowie’s fortunes. He later recalled wondering, whilst playing for crowds who’d come to hear his latest hits, “how many Velvet Underground albums these people have in their record collections?”. The disillusionment infected albums like Tonight and Never Let Me Down, which he would dismiss as his “Phil Collins years”, eventually abandoning his solo career in an attempt to rejuvenate his rock’n’roll spirit with a guitar band, Tin Machine.

A back-to-basics exercise whose two albums feature brittle hard rock on the cusp of Sonic Youth-style noise-rock, Tin Machine failed to secure either critical approval or commercial success. While Bowie had often been regarded as someone out of step with current trends, it was the first time this was used in a pejorative sense.

It would be an impression he would struggle to shake off through the Nineties and Noughties, as successive albums seemed less like voyages into brave new worlds as stumbles down blind alleys. And while the albums weren’t bad, they weren’t all that memorable, and sometimes appeared like token exercises: there was the art-rock concept album, Outside; the industrial/drum’n’bass album, Earthling; the maundering Hours…; and Heathen and Reality, albums on which Bowie’s apparently waning powers were confirmed by the inclusion of cover versions, and not particularly good cover versions at that. It was almost a blessed relief when, following the latter’s appearance in 2003, he quietly retreated from music to pursue other artistic interests.

And to be honest, nobody really noticed: the music industry can always generate more than enough ephemeral fizz to keep people distracted, so it was only when the single “Where Are We Now?” appeared on Bowie’s birthday ten years later, shortly followed by The Next Day, that we realised how much his distinctive creative input had been missed. From the album’s cover image – a sly palimpsest of his “Heroes” sleeve – to the music, it presented a revitalised Bowie mining memories in an elliptical manner, so that songs crackled with echoes of earlier work whilst sounding fiercely contemporary. It was one of the greatest comebacks in music history, though only in hindsight does the prevalence of death and violence in many of the songs seem to offer dark portents.

Since then, the V&A’s Bowie exhibition curated a museum summary of his career, while the jukebox musical Lazarus offered a surreal adaptation of the stranded-alien theme of The Man Who Fell To Earth; and finally, just days before his passing, the challenging Blackstar presented Bowie’s final musical statement, one determined to keep pushing boundaries right to the very end. Significantly, its cover bears no image of the singer himself; just a star, singular and utterly unique.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments