Forget Led Zeppelin and the Eagles – the new sound of classic rock is ‘shoegaze’ and Nineties indie

The days of baby boomers defining the genre are gone, says Michael Hann – thanks to TikTok and shows like ‘The Bear’, a new generation is in thrall to the grungey throwback sounds of bands like Hole, The Replacements and Slowdive

Everyone knows what classic rock is, right? It’s Led Zeppelin, Queen, the Stones, the Eagles and the like. It’s men in tight trousers singing about red hot mommas, while other men in tight trousers play their guitars with their feet on the monitors. It’s the sound of the 1970s, of vast arenas in the Midwest – such as Detroit’s Cobo Hall, where Bob Seger and Kiss both recorded landmark live albums. It’s an American radio format – the sound of baby boomers at play – for listening to while driving down open roads in a vast landscape.

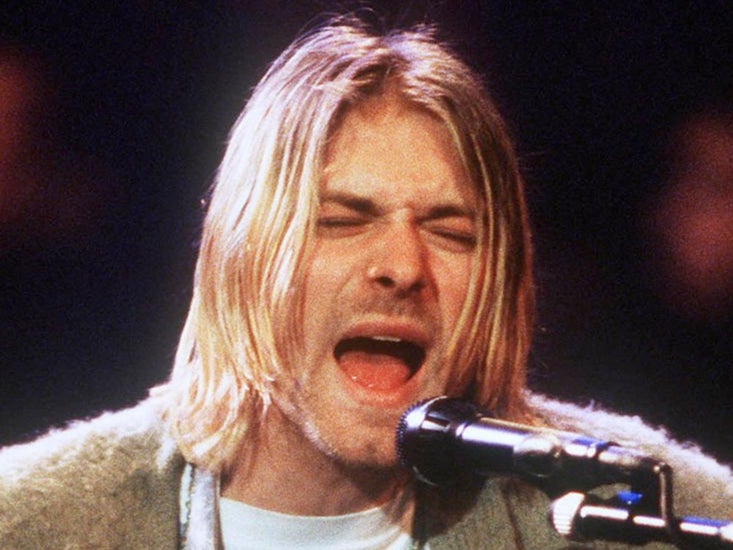

It’s certainly been that. But maybe it’s becoming something different now. Maybe it’s now Nirvana, and Pavement, and Hole and the like. Perhaps it’s men and women singing about how woeful life is while guitarists stare at their shoes. Perhaps it’s the sound of the 1990s, of sweaty clubs in big cities, of bedrooms festooned with posters. Perhaps it’s the music of TV soundtracks, or a TikTok phenomenon. Perhaps it’s the sound of Gen Xers at play, migrating to a new generation. Maybe alt-rock is now the generic nostalgic touchstone for some long-lost halcyon days.

Certainly, Nineties-style alt-rock feels very prevalent at the moment. It’s there in young bands: Bar Italia, the hip young British indie band who are signed to the venerable Matador label, sound very much as though they could have been signed to Matador in 1993. Anyone who goes to new band nights will see groups faithfully recreating the sound of The Dublin Castle in north London 30 years ago. It’s all over TV: the soundtrack to The Bear, about a restaurant in Chicago, was dripping not with the soundtrack of modern-day Chicago, but with REM and Wilco and The Replacements – the sound of middle-aged white people, despite its multi-ethnic and largely young cast.

“It’s the cycle of music, and its regurgitation in fashions and fads,” says Nat Cramp, who runs the shoegaze label Sonic Cathedral (shoegaze is everywhere at the moment: the new album by reunited Nineties veterans Slowdive, astonishingly, reached No 6 in the UK, their highest ever chart placing). He notes that we’re at a point where the people who grew up on Nineties music are now in positions of influence in the media, and so they can flood the world with their personal tastes.

Shoegaze – the microgenre of alt-rock defined by breathy, ethereal vocals and gauzy, effects-laden guitars – has been a particular success on TikTok. “It’s a good standby for that slightly melancholy but euphoric backdrop for TikToks,” Cramp says, before noting the success of a more recent shoegaze band. “Beach House are huge on TikTok – I came home one day and my son was playing them. I asked how he knew about them, and he said, “Everyone knows Beach House – they’re massive.” Slowdive’s Nick Chaplin recently spoke about his 12-year-old daughter discovering that the band she and all her friends loved from TikTok was the one he played bass in.

What is it about this music of the past that is appealing to younger people? Hannah Jadagu, a 21-year-old musician based in New York, says lots of her university friends love Nineties indie music. “I think it’s a combination of a few things. I think the art of nostalgia is a big thing with twentysomethings – it’s a moment where you’re trying to find yourself. And also, it’s what you might perceive as being cool: a lot of what’s cool these days is what’s old, and what you were never a part of, but you long for.”

OK, that’s the psychological part of it. But what about sonically? What is it about the music that is getting seized on?

“Guitars. Take Kurt Cobain, for instance, and the distortion, the grunge aspect: it can be really soothing and calming to people. Musically, it’s definitely the guitars – how heavy it hits, and how it has a dynamic range of going from very loud to very soft. The range is really captivating for a lot of people. At least, for me it is.”

“It’s a reaction to bedroom pop, stuff that people made in two hours sitting alone in their apartment,” says Sabrina Teitelbaum, 26, who records as Blondshell. “I think, partially, people going back to the Nineties is them being hungry for that kind of production, where it would be Steve Albini, in a studio, working to perfection.”

Teitelbaum was absolutely explicit about bringing Nineties influences to bear on her debut album, released earlier this year.

“I had all of these songs that I had been writing alone in the pandemic, influenced by the Nineties, influenced by Courtney Love, because that’s what I was listening to. I was going through stuff personally, and the records that were speaking to me were stuff like Siamese Dream [by Smashing Pumpkins], or Live Through This [by Hole]. And so, when I brought those songs in to record them, I was like, ‘Here’s what they’re influenced by, here are the parts of this era that I really want to keep in the production.’ The guitar tones were influenced by that. That was a big part of it.”

Guitar tones seem like a technical side issue, but in many ways they are at the heart of the matter. Because of the developments in technology, it’s now far easier for young musicians in their bedrooms to replicate any sound they have heard in the past (and streaming and YouTube give them the chance to hear far more sounds than the musicians of 30 years ago did).

When we were kids, there’d be the 20th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s, and it would feel like the biggest thing in the world. Now that’s what they expect of bands – you’re supposed to tweet for the 13th anniversary of some f***ing single

“You can dial up any sound, and go through an amp plug-in,” says Nic Offer, the singer of !!!. “Whatever you want, you can do.” If you want to make a shoegaze record, he says, you can just watch a YouTube tutorial, get the plug-in, and you’ve got the sound. “Whereas when I was a teenager going to Ride concerts, I didn’t know how you could do that. I couldn’t afford to buy all those pedals.”

Mac MacMaughan, who co-founded the influential indie label Merge in 1989, and is the singer-guitarist with Superchunk (who have a new career-spanning box set out next week), also notes that it’s actually easier now to sound like the 1990s than it is the 1970s, because of the death of analogue recording.

“Take Dinosaur Jr. If you’re my age, when they came out, you went, ‘Well, they kind of sound like Neil Young.’ But if you play them next to Neil Young, they obviously don’t sound like a Neil Young record because of the vintage recording techniques [on 1970s albums]. Nowadays, you can only get as close to Neil Young as Dinosaur Jr could. If you really want to sound like someone making a record in 1975, you’d have to go out of your way to do that. You don’t really have to go too far out of your way to make a record that sounds like Superchunk in the early Nineties.”

For older musicians, there’s a sense of pleasure as well as bemusement at seeing young artists replicating the past, and sometimes their past. MacMaughan has felt that in recent years. “As an old person, it makes me think, ‘Oh yeah, other people still like the same kind of feeling they get from playing this kind of guitar music as we did back then.’”

That said, he notices that younger bands are rarely playing everything completely straight. “It’s a little bit like when REM started. I remember all these reviews that were comparing them to The Byrds. And when they did a Velvet Underground song, people compared them to the Velvets and to these other things that were before my time. And yes, they were clearly influences on them, but they didn’t sound like any of those bands. They just sounded like REM. And so what’s happening now feels a little bit like the classic rock progression.”

That’s the element that sometimes gets forgotten: that lots of the alt-rock bands were themselves products as much of old-fashioned classic rock as of punk and post-punk. The Replacements – one of the ur-bands of US alternative rock – were at heart punks playing classic rock. A few years ago, I put it to Black Francis that Pixies were, at heart, a classic rock band who happened to sing about different subjects. He laughed and replied: “That’s what we all grew up with. And that’s still what we tend to gravitate toward when we listen to rock music. Certainly, that’s what I gravitate to.”

Britt Daniel, of the brilliant Texas band Spoon – who have developed a 25-year career playing stark and spare rock music strongly informed by post-punk – feels the same. “When we started, there wasn’t anything cooler to me than Wire,” he tells me, “but I was never ashamed to love the Stones or Zeppelin. In my covers band at school, we covered Joy Division, The Romantics, Zeppelin, The Cure and The Doors. I never thought that was too uncool.”

Daniel also notes that TV has long been a friend to alt-rock, and that it’s not just The Bear; US TV shows have been crucial in both putting it and keeping it in circulation. Think of The O.C., the early Noughties teen drama with a soundtrack packed with guitar bands. “If I think about any specific sync that really seemed to reach people, then it was that show The O.C., which was a phenomenon. A number of people told me they first heard of us on that show. I don’t hear that comment a whole lot about other shows, so I know it must be doing something.”

It turns out that Daniel and Nic Offer had been talking about the classic “rock-isation” of alt-rock independently. “Britt and I were talking about how when we were kids, there’d be the 20th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s, and it would feel like the biggest thing in the world,” Offer says. “And now that’s what they expect of bands – you’re supposed to tweet for the 13th anniversary of some f***ing single.”

Offer notes that alt-rock is now a huge driver of the nostalgia business – as opposed to the emotion of nostalgia. “I went to see the new print of Stop Making Sense [the Talking Heads concert movie first released in 1984]. Last week they reissued Tim [by The Replacements]. The Cure was one of the biggest tours of the summer. It just feels like we’re at the age where our nostalgia is marketable. The boomer generation has been sold to us so many times, and it seems like this is the new market.”

But to the kids picking up guitars and plugging in pedals, none of this seems cynical. One weekday evening in September, I go to the St Moritz Club in central London. I feel – and am – old enough to be a parent to everyone else in the queue to get into the tiny basement. Once inside, I take my spot to watch a band called Night Swimming take to the stage. They can barely fit on it: two members have to turn sideways so they don’t bang each other with their guitars. And then they plug in and start playing: the guitars shimmer and the voice of the young woman singing floats on top. To me, it’s the sound of the Thames Valley in 1993, the sound of shoegaze. To the band and the rest of the crowd, though, it’s the sound of now.

The Superchunk box set ‘Misfits & Mistakes: Singles, B-Sides and Strays 2007-2023’ is released on 27 October on Merge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments