London Calling at 40: How The Clash shattered punk orthodoxy and created a masterpiece

As The Clash’s seminal third album is celebrated in a new exhibition, Chris Harvey reflects on its anger, humour and swaggering grandeur

Martin Scorsese once described “Janie Jones” by The Clash as the greatest British rock’n’roll song. One of the many wonderful things about that statement, not lost on Clash fans, is that however charged-up-and-ready-to-blow the opening track of the band’s eponymous 1977 debut album is, it’s not even the greatest Clash song; hell, it’s not even the greatest opening track on a Clash album. There’s serious competition for that accolade on each of their studio albums, but the title track of London Calling fights off all comers. Its ringing apocalyptic alarm announced the most extraordinary album of the late Seventies, which, almost unbelievably, was released 40 years ago next month on 14 December. It’s even being celebrated in its own exhibition at the Museum of London.

London Calling landed at the close of an extraordinary year in Britain. In 1979, Margaret Thatcher won her first Tory majority, ending the era of post-war consensus politics, and replacing it with a no-compromise, anti-protectionist, monetarist regime that would preside over denationalisation and the decimation of Britain’s traditional industries. The class warfare that had simmered below the surface of British society since 1945 would be openly waged by the Thatcher government, which would mobilise the state against its people and let free-market economics do what it would. The echo of its mantra – “a price to be paid” (three million unemployed) – can still be heard today in talk of “short-term pain” (watch this space). In 1977, The Clash had demanded “a riot of our own”; Thatcher was ready to respond with mounted police, truncheons, and the army if necessary. “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony” indeed.

But all that was still to come (as was The Clash’s musical response to it): 1979 was aberrant in other ways. A sitting MP – Airey Neave – was blown up and killed by an Irish republican bomb as he drove out of the Houses of Parliament; another, the former leader of the Liberal Party, Jeremy Thorpe, was on trial for incitement to murder. The Yorkshire Ripper was at large. Sid Vicious, on bail awaiting trial for the murder of his girlfriend Nancy Spungen, died of a heroin overdose. Had punk’s promise come to this?

The Clash, meanwhile, had lost their standing as the movement’s most resolutely anti-commercialistic band when they had Blue Öyster Cult producer Sandy Pearlman drape their second album Give ‘Em Enough Rope in the power-chord sheen of American rock. Whether or not it was an attempt to crack America, it was a long way from “we’re a garage band” and “I’m so bored with the USA”. The band felt “bruised by the experience” and by the criticism they had faced, says filmmaker Don Letts, who documented what happened next in his compelling The Last Testament – The Making of London Calling (2004). Singer Joe Strummer himself told NME: “We’ve had our fill of bullshit, and now we’re back to the drawing board. We’re really f***ed, but I don’t think we’re f***ed enough to quit. We’re way beyond that!”

“Their backs were against the wall,” says Letts. There was a sense, he adds, that they needed to “hunker down” and redefine what The Clash should sound like.

The result – London Calling – would prove beyond doubt that trying to sound like a big US rock band was a waste of time, because, in 1979, the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world sounded like The Clash.

“London Calling celebrates the romance of rock’n’roll rebellion in grand, epic terms…” wrote Rolling Stone, “…it digs deeply into rock legend, history, politics and myth for its images and themes. Everything has been brought together into a single, vast, stirring story.”

It was a double album: 19 tracks. Not all were classics (does anyone really love “Lover’s Rock” or “Wrong ’em Boyo”?), but almost all demanded to be included. And from track two, the deranged psychobilly cover of Fifties British rock’n’roller Vince Taylor’s “Brand New Cadillac”, it was clear that London Calling wasn’t going to be quite like anything else. By the time you reached the jazz guitar and whistling that leads into track three, “Jimmy Jazz”, all bets were off. That side one ended with the exuberant ska pop of “Rudie Can’t Fail” showed that this wasn’t an album that opened with its one great song; they were just going to keep on coming.

Side two signalled a step change in Strummer’s lyrical concerns. “Spanish Bombs” introduced spotty teenagers across the world to the Spanish Civil War: “The freedom fighters died upon the hill/ They sang the red flag/ They wore the black one”. “Lost in the Supermarket”, sung by guitarist Mick Jones, showcased one of The Clash’s secret weapons, that high, girlish, heartfelt voice of Jones, which mixes ardour with the pang of something lost. It gave The Clash a soulful instrument other punk bands didn’t have. And, ironically, it helped The Clash break America, when it was put to use on “Train in Vain” – not listed on the album, except for where it was scratched on the run-off groove – which had a run at the US Billboard chart.

For Letts, though, the album isn’t about the greatness of individual tracks, though he has a place in his heart for “London Calling” and bassist Paul Simonon’s “The Guns of Brixton”. It’s about the juxtaposition of musical styles from far and wide.

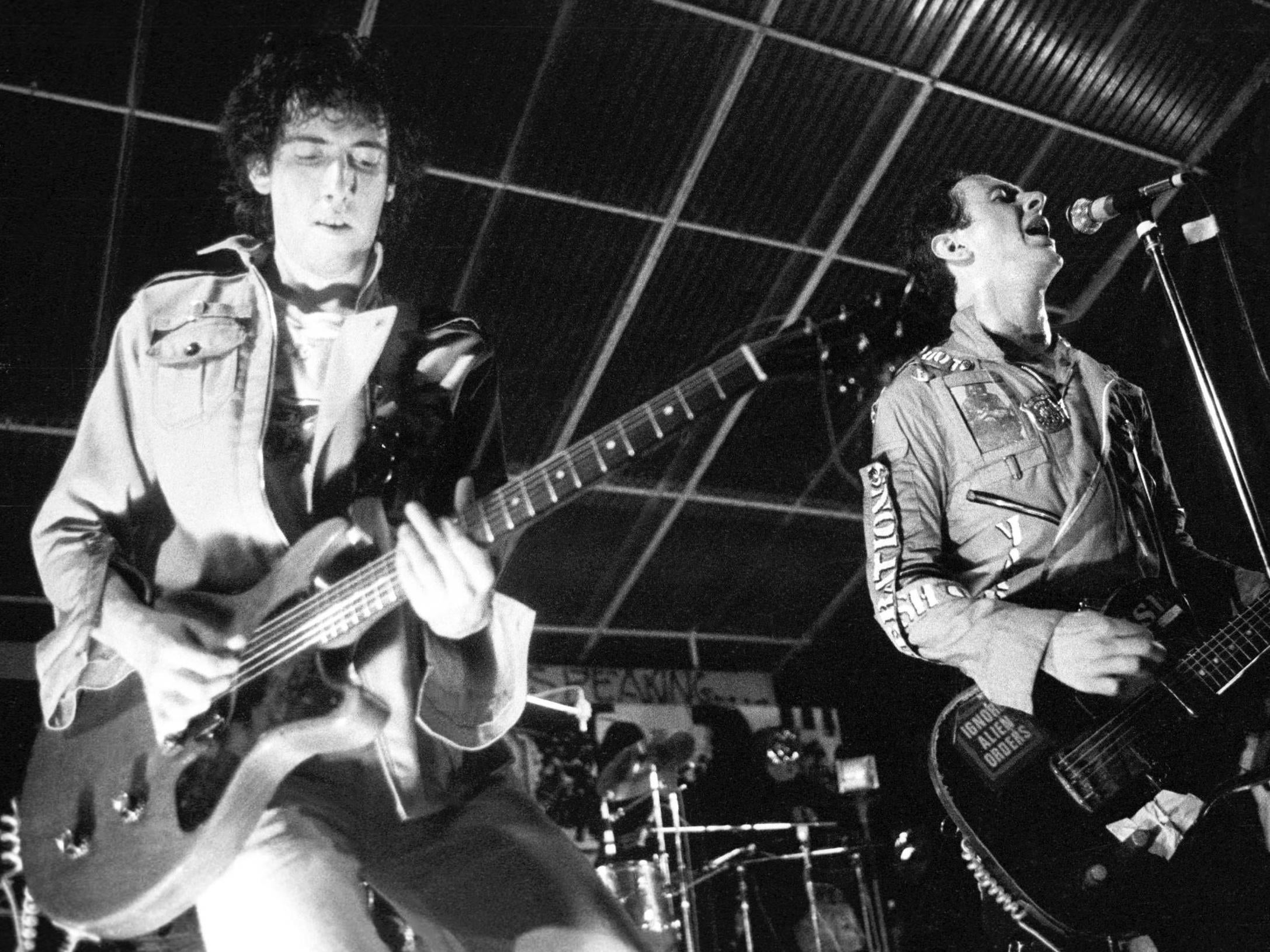

Letts had first come into contact with the band in west London in the mid Seventies, when he noticed two lone skinny white boys [Simonon and Strummer] in a basement reggae club. He recalls thinking it was pretty brave at the time. He recognised them later when they wandered into the clothes shop he ran on the King’s Road in Chelsea, Acme Attractions, but it was his then girlfriend Jeanette Lee – later to join PiL – who first took him to see them play at an out-of-the-way venue in northwest London. The energy of the band on stage was like nothing he had ever seen before.

From then on, their careers would be intertwined. Letts was the DJ at the Roxy in Covent Garden, where The Clash played on New Year’s Day 1977, and was an early chronicler of the band on Super-8. He shot the videos for “White Riot”, “Tommy Gun” and, in 1979, the famous promo for the “London Calling” single (which went to No 11 in the UK).

The album, Letts notes, was a rejection of what other people thought the band should play or sound like, and signalled they were just going to play what they liked, whether that was rock or reggae, pop or blues. This was no three-chord wonder. There was piano, acoustic guitar, many different drum signatures. “They couldn’t have made that album without [drummer] Topper Headon,” says Letts. “He could play anything.”

In some ways, London Calling was not even the most radical UK album of 1979. The Slits released Cut, PiL’s experimental Metal Box opened with 10 and a half minutes of the near unlistenable “Albatross”, The Pop Group set off a post-punk chain reaction with Y, while Joy Division subtly tilted rock on its axis with Unknown Pleasures. London Calling only just made NME’s top 10 albums of the year, at number eight. Meanwhile, in Coventry, the 2-Tone movement was producing multiracial bands that did more than just pay homage to Jamaican music like the punks.

But London Calling had something unique. It was lightning in a bottle. All the shades of The Clash’s music – anger, passion, swagger, political fury, romantic heroism, anguish, dread, hope, innocence, humour and exhilaration – had been caught by producer Guy Stevens. It had street smarts and grandeur. In The Last Testament, Clash guitarist Mick Jones was at pains to point out that the songs had already been written, the arrangements already worked out, during a sustained period of intense writing and rehearsing at Vanilla Studios, behind a garage in Pimlico, before Stevens arrived on the scene. But the producer, a famously erratic alcoholic, whose techniques, as Letts’ film shows, were unconventional to say the least, wanted something more. Smashing chairs, pouring wine over a piano as Strummer played, swinging a ladder violently around his head, Stevens captured the spirit of The Clash. As the band’s former manager Kosmo Vinyl puts it in a quote from the Museum of London exhibition: “Guy Stevens wanted to make a record that sounded like scoring a goal at a Wembley Cup Final.”

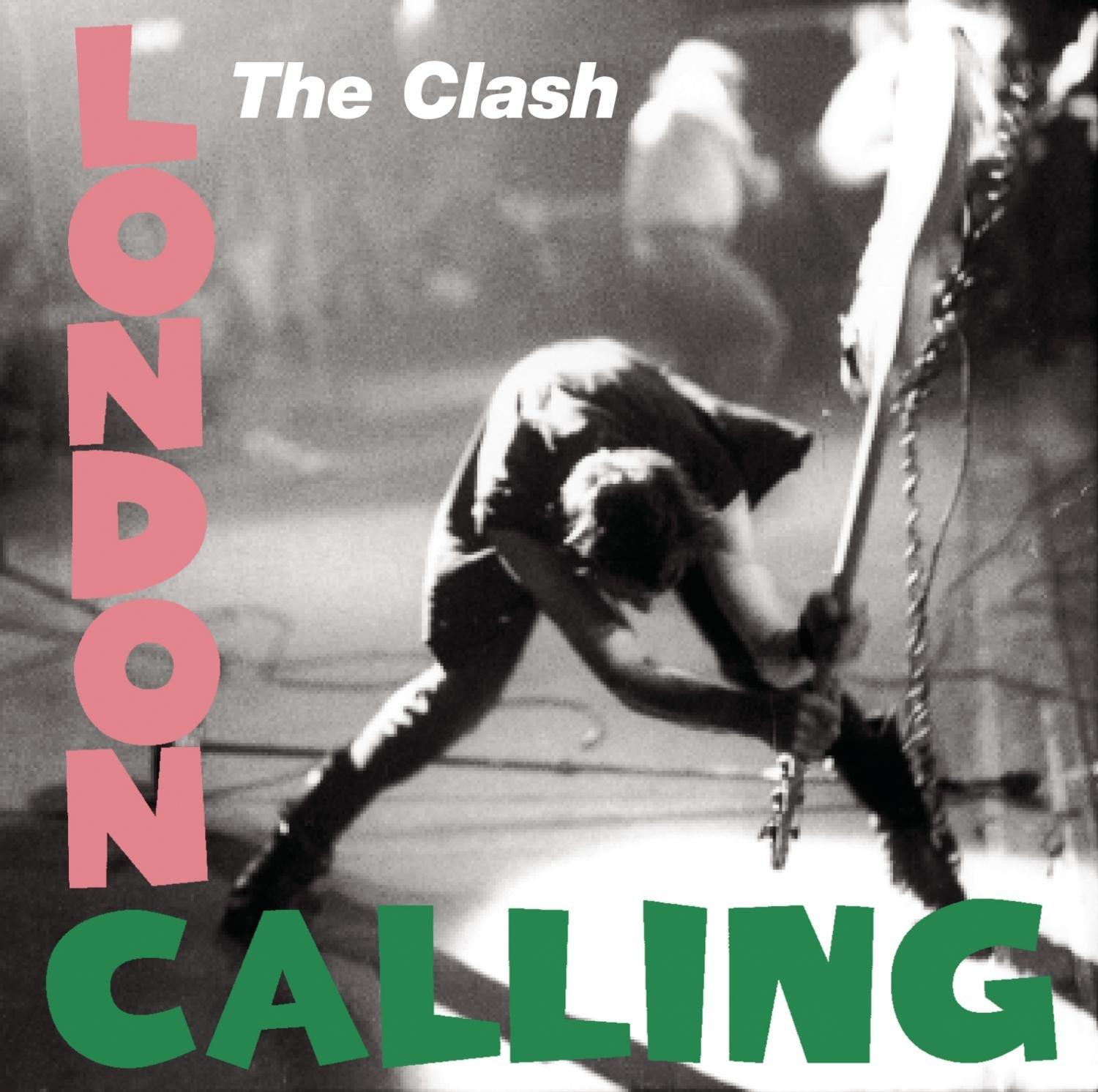

The curator of The Clash: London Calling exhibition, Robert Gordon McHarg III, remembers hearing the album as a teenager growing up in Canada. The track that spoke loudest to him then was “Clampdown”, with its anti-establishment, anti-nine-to-five ethos, although these days, he says, he is drawn to “The Card Cheat” from side three. McHarg moved to London in 1983, met Simonon at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1989, and Strummer shortly after. He now looks after the 20,000 items in the Joe Strummer archive, from which treasures such as the original lyrics written for “Ice Age” before it became “London Calling” will be on display, alongside items such as Simonon’s smashed bass from the album cover shot by Pennie Smith. The cover’s graphic design, incidentally, based on Elvis’s debut album from 1956 was the last straw for some punks, who had taken the “no Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones” line from the B-side of “White Riot” to heart.

The photos chosen by designer Ray Lowry for the sheet inside the original sleeve have been blown up so they can be viewed properly for the first time – they were sourced, says McHarg, from the negatives of nearly 40 rolls of film. “Those alone, I think, would make it worth coming to the exhibition,” agrees senior curator Beatrice Behlen. There are 150 artefacts, she tells me, confiding that it was a stipulation that none of the labelling could be construed as bragging, as “The Clash don’t brag”.

The exhibition, McHarg adds, “is a pretty fun experience”, and includes a mixing desk where you can listen to the individual guitar, bass, drum and vocal tracks that make up the songs.

Does he feel that punk became restrictive for the band – and Strummer in particular, who adopted its speech mannerisms and attitude in a way that completely belied his son-of-a-diplomat, boarding-school upbringing, and even his years as a hippie squatter? “I’ve worked so much with Joe’s archives,” he says, “that [I can tell] there was never a change in attitude within his spirit. His sense of integrity was [the same] throughout, whatever music he was into. If you listen to his lyrics throughout his lifetime, he was always a passionate rebel.”

I ask Letts if he thinks Strummer, who died in 2002 at the age of 50, had a sense of his own musical legacy and whether he had a favourite album. “Joe was very hard on himself,” he says, softly. “I don’t think he was ever satisfied with anything he’d done.”

We were, Joe.

London Calling shattered punk orthodoxy and inspired bands from U2 to Beastie Boys to Manic Street Preachers. Artists as diverse as Bruce Springsteen, Metallica and The Strokes have played songs from it on stage. Even the Pet Shop Boys’ Neil Tennant has professed his love of the band. Rolling Stone has London Calling rubbing shoulders with Dylan and The Beatles in its top 10 albums of all time. It’s now literally a museum piece, but its rebellious spirit lives on.

The Clash: London Calling, Museum of London, 15 November – 19 April 2020, admission free. The London Calling Scrapbook, released to mark the 40th Anniversary of the album, is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks