‘What the hell is this dude doing playing acid jazz?’: How the 1990s Cork music scene helped make Cillian Murphy an Oscar-winning star

Decades before he became an Oscar winner for his performance in ‘Oppenheimer’, the Irish actor was one of a group of ‘goofy teenagers’ trying to make it as rock stars. Ed Power speaks to friends and peers who knew the star when he was trying to get his band – named Sons of Mr Green Genes – off the ground

If you were young and carefree and lived in Cork in the early Nineties, at some point you’d have come across an up-and-coming new band led by a skinny frontman with an earnest gaze and a sensible haircut. The group was Sons of Mr Green Genes – freewheeling funk ragamuffins who took their name from a wacky Frank Zappa song. Their singer was a shy teenager named Cillian Murphy.

He was musically talented and not uncharismatic. But nobody who piled in to see Mr Green Genes in one of Cork city’s many pokey indie venues could have had an inkling they were watching a future Hollywood star. It would have blown their minds to know Murphy, 47, would triumph at the 2024 Oscars, winning Best Actor for portraying the father of the atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer, in a lavish biopic.

“I remember going to see his band in The Shelter. And I was like, ‘What the hell is this dude doing playing acid jazz?’ It wasn’t going with the grain at all,” recalls Morty McCarthy, drummer with Cork indie icons The Sultans of Ping. “You had the indie scene in Cork – the Sultans and the Frank and Walters. Then you had [legendary acid house night] Sweat. Acid jazz was a brave move. They could all play. They were probably better players than us [the Sultans] at the time. [Murphy] definitely didn’t stand out. He would have been quite young.”

Murphy was still at school when he formed Mr Green Genes with younger brother Pádraig (keyboards) and friends Bob Jackson (drums), Chris McCarthy (bass), and John Ahern (lead guitar, vocals). “They came to me with demo tapes. I’d say Cillian was about 15, Paud was about 13,” recalls Joe Kelly, a local music promoter who would later book Sons of Mrs Green Genes as his house band at a club night in the city.

“They were young. They handled it in a goofy teenage way. They knew I had some relationship with music. Back then, it was expensive to record demos. It was one song if memory serves me correct. [Murphy] wasn’t a show-off or anything. He wasn’t doing Mick Jagger. He used to play guitar and sing – I would argue he was more musician than frontman.”

Obsessed with music, Murphy continued to prioritise the Green Genes when he started a law degree at University College Cork. Having played steadily around Ireland’s second-largest city, the band began to attract record company attention. At one point, London label Acid Jazz – co-founded by DJ Gilles Peterson – expressed an interest.

“They were fantastic,” Acid Jazz’s Eddie Piller said in 2012. “They were very young, maybe under 18. They reminded me of a band on my label who had split called Corduroy. I wanted to find a replacement. So we tracked this little band down. I went to see them in Cork and we negotiated with them for some time.”

By then, though, Murphy’s acting had started to eclipse the Green Genes. In 1995, a local experimental theatre company, Corcadorca, put on a stage version of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange at Sir Henry’s nightclub. It had a profound impact on Murphy, who attended with friends.

Fired up by Clockwork Orange, Murphy approached Corcadorca founder Pat Kiernan and suggested he cast him in his next production. “I was pestering Pat about doing plays,” Murphy told The Irish Times in 2016. “Eventually, I was Interrailing in France for the summer, and, however it happened, the script got sent to my tent. That’s where I first read it. It was my very first time reading a play outside school: that’s how theatre illiterate I was.”

The script was for Disco Pigs, an intense two-hander about a couple in a destructive relationship set in a surrealistic alternative version of Cork – “Pork City”. It was written by Enda Walsh, a Dubliner transplanted to Cork who would later collaborate with David Bowie on his musical Lazarus. When he met Murphy, he knew he was perfect for the part.

“He read one of the speeches, and I thought, he’s a f***ing brilliant actor,” Walsh later recalled. “He had this understanding of music or sound. Whenever he spoke the test, he was basically singing. We were very, very fortunate to get him.”

Acting became Murphy’s passion. Sons of Mrs Green Genes faded away – as did Murphy’s educational aspirations (he dropped out of UCC shortly afterwards). The success he has since enjoyed is entirely down to his talent and perseverance. He’d had his years of struggle until Danny Boyle cast him in fast-moving zombie horror 28 Days Later in 2002. Things could easily have not worked out.

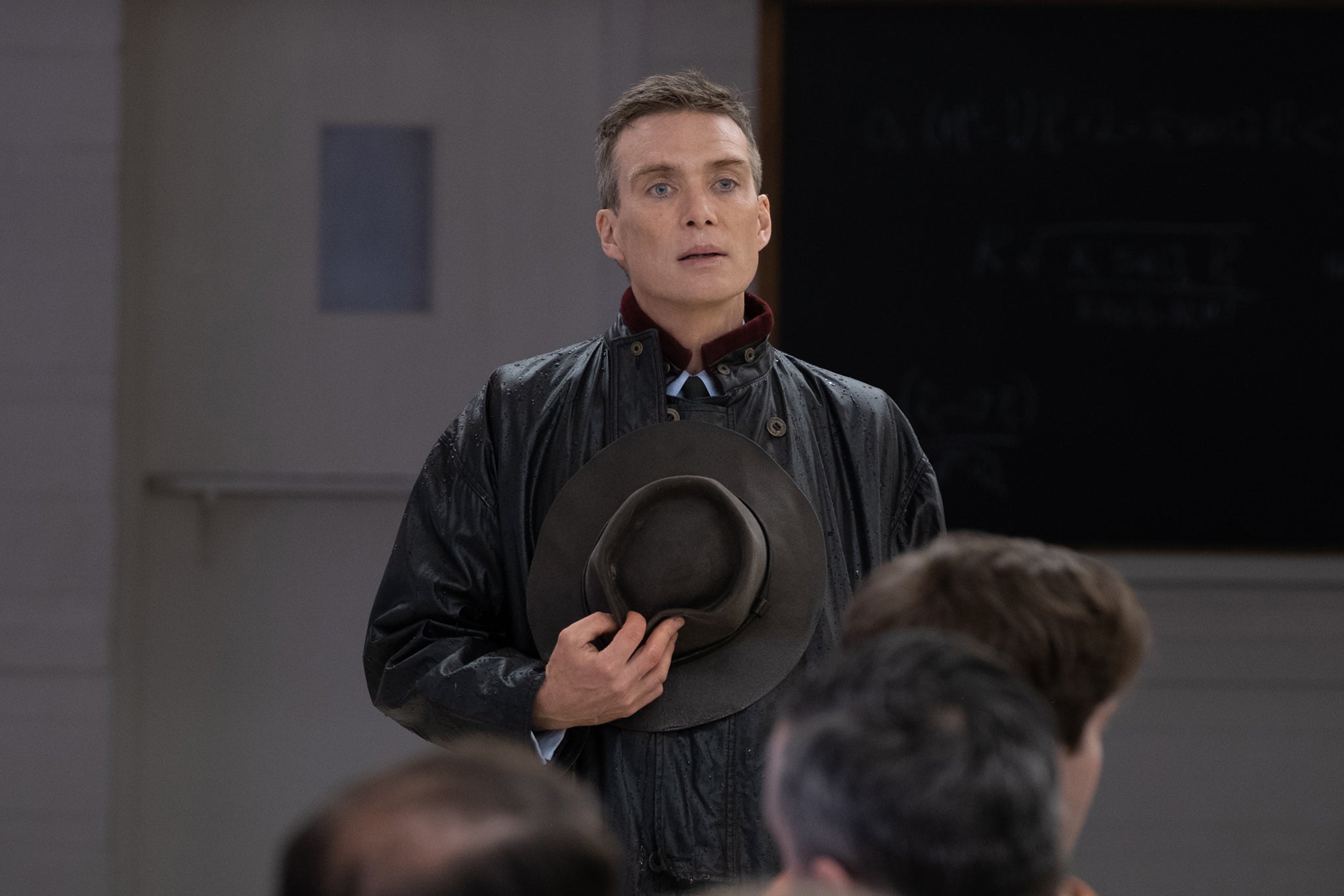

But he kept at it. He would go on to work with Ken Loach in The Wind That Shakes the Barley, a leftist take on the Irish War of Independence, and to excel in smaller parts in Christopher Nolan blockbusters such as Batman Begins and Inception – before becoming famous as Peaky Blinders’s flat-capped anti-hero Tommy Shelby.

He brought a mercurial quality to these roles and a fascinating ambivalence. That was especially true of Peaky Blinders – which teetered on self-parody in its final seasons, when a Nick Cave-scored montage always seemed just around the next corner. Amid the escalating hokeyness, Murphy’s Tommy was always compelling – he made the viewer believe in the creaky caricature of a villain with a heart of gold. And now, comes his crowning moment with Nolan’s Oppenheimer, in which he plays a physicist struggling with the one thing beyond the reach of science: his conscience.

Amid all the glitter, Murphy has always maintained a love of music. He is a semi-regular guest presenter on BBC 6 Music, where his “nocturnal mix-tapes” have featured such eclectic selections as Portishead, Aretha Franklin, A Tribe Called Quest and Low. He has, in addition, appeared on stage with artists such as The National’s Bryce and Aaron Dessner, with whom he performed a spoken word piece during the Sounds from a Safe Harbour festival in Cork in 2017.

He has also stayed close to his roots. He and his family moved back to Ireland several years ago and he celebrated his 40th birthday by hiring the Connolly’s of Leap venue in West Cork and having local indie heroes The Frank and Walters perform. As they bashed out their early hit, “After All”, it is tempting to imagine that Murphy was transported back to the early 1990s, when Cork was an artistic hotbed, where you could play acid jazz with your fellow Frank Zappa devotees one day, perform in an avant-garde play the next.

“There was a lot of theatre going on,” remembers Cónal Creedon, a novelist and playwright whose work has been performed by Corcadorca. “A lot of that was because of unemployment. Everyone seemed to be a musician, a songwriter, a playwright, a poet. There was nothing to fill your time with.”

Murphy’s Sons of Mr Green Genes were part of a rich Cork tradition of bands that embraced idiosyncrasy. Whether it was 1980s and groups such as post-punks Five Go Down to the Sea? or fraught soft-rockers Microdisney or Nineties successors such as the Sultans and Franks, Cork groups were always playful and inventive – much less po-faced than Dublin with its endless supply of Bono-wannabes and a tragic fixation with whatever was popular in the UK.

The clubbing scene was also booming. In 1988, two DJs, Greg Dowling and Shane Johnson, began hosting a house night, Sweat, at Sir Henry’s on North Main Street. Much like Manchester’s Hacienda, it became a beacon for clubbing culture. Henry’s was also the location of an August 1991 appearance by Nirvana, who began their European tour supporting Sonic Youth in Cork. As the band shuffled out and plunged into “Drain You”, they inscribed themselves into the city’s musical history.

“It was just so noisy and raucous,” John “Haggis” Hegarty of Cork shoegaze group Emperor of Ice Cream told me last year. “Afterwards, Kurt walked off to the side. Morty from the Sultans was at the door; he said, ‘Come in quick.’ [Backstage], there was a circle around Kurt Cobain. Kurt was on the ground, driving his hand into the guitar, with blood spitting everywhere. I remember thinking, ‘Holy s***, this guy is plugged in.’”

Cobain’s visit aside, Cork was geographically and culturally isolated – in ways both negative but positive. “I remember speaking to [Sweat DJ] Greg Dowling. When he moved to Cork, there was a massive reggae scene,” recalls McCarthy. “He had come from Dublin. He was saying, ‘What the hell is going on in this city? Why is there a reggae scene here? ‘It was so isolated.”

McCarthy didn’t keep up with Sons of Mr Green Genes. Instead, he and The Sultans of Ping relocated to London and had a big hit with “Where’s Me Jumper?” Then, in September 1997, he heard a buzzy new play from Ireland called Disco Pigs was coming to the UK. He bought a ticket and was blown away by Murphy’s performance. He knew he was witnessing a special talent – an actor for whom greatness surely beckoned.

“The Sultans moved to London. Disco Pigs came to the Bush Theatre in Shepherd’s Bush. We were all reading about it. I cried through the whole thing. It was one of the most powerful things I’ve ever seen. I couldn’t believe it. Here was this guy who was in an acid jazz band – and then he finds his calling.” He takes a breath. “It was really powerful.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks