Bryan Adams: ‘I only wrote Summer of ’69 because it made me laugh’

The singer who broke the UK singles chart record in the Nineties has been selling out arenas ever since. He talks to Michael Hann about coping with sudden stardom, songs that ‘climb out of the wreckage’, and the ageism of radio stations

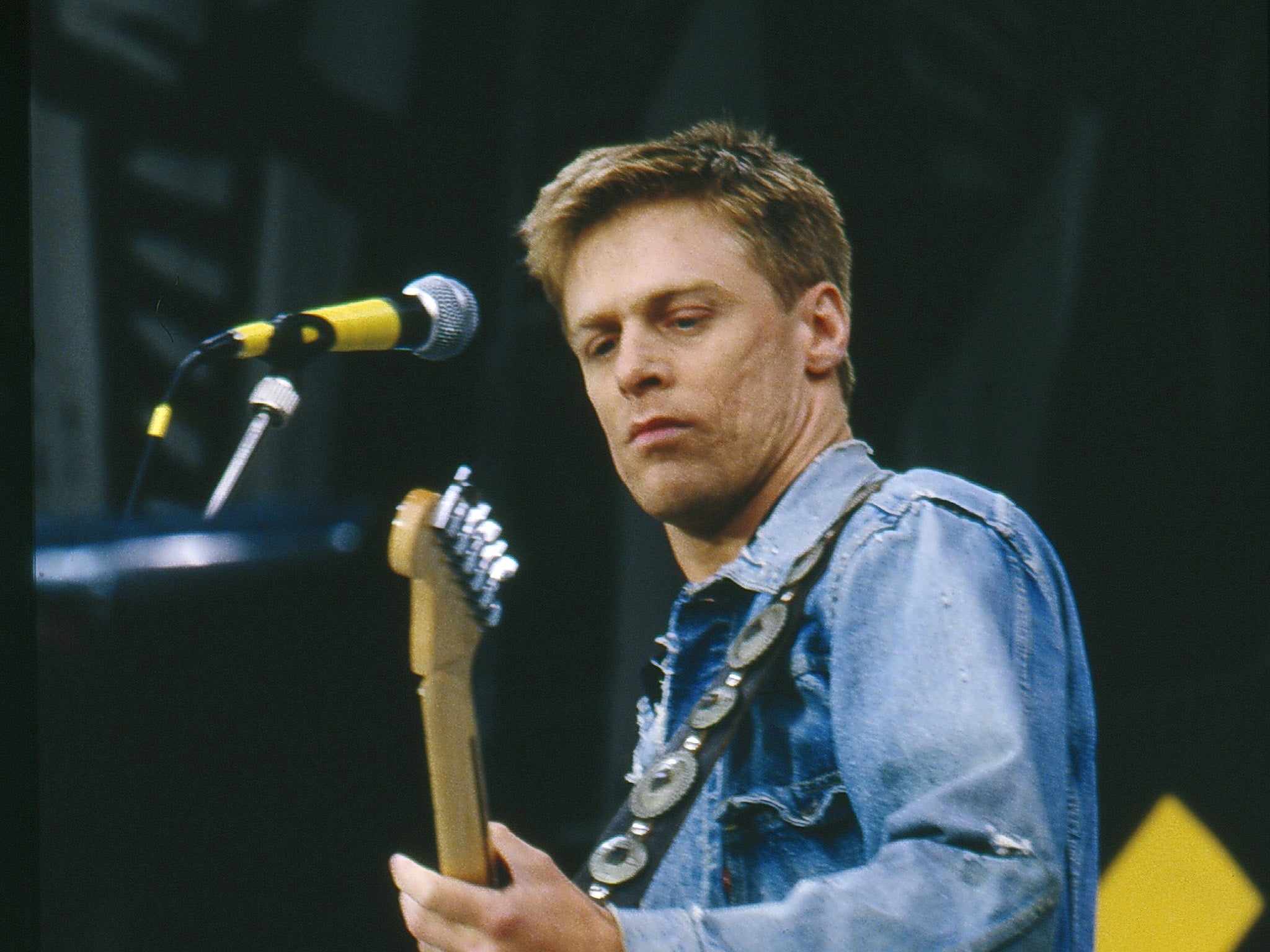

Bryan Adams rose to fame and success as a rock everyman. Even when he was No 1 in the UK for 16 weeks with “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You”, the clip that Top of the Pops showed over and over again featured Adams looking less like a rock star than a man who’s realised he has to pop back to B&Q for some more creosote. In the Eighties, when being a gruff-voiced man of the people from North America (Adams is Canadian) was a desirable trait in a rock star, he became enormous – his 1984 album Reckless sold five million copies in the US alone – but he never seemed to be a rock star. He was big; he just didn’t project it.

The irony is that Adams is not and was not an everyman. His life was not and is not like yours. He was an army brat as a kid, and lived all around the world, following a father whom he has previously said had a violent temper. He started pursuing rock’n’roll as a kid and never stopped. He puts it blandly – “I didn’t really have any other job. So I had to make it work” – but you can be sure most everymen would have taken that other job, because that’s what everymen do. Even now, in his sixties, a reliably arena-filling brand, he’s also a noted photographer, and he writes musicals too. This is not a man who happened to luck into things with an “Aw shucks” shrug.

He’s so not an everyman that when asked what was the last thing he had to do for work that he really didn’t want to do, he can’t think of anything. Which makes him either the most amenable man in the world, or someone who has known such success he doesn’t have to waste time on rubbish.

One gets an idea of his determination when he talks about deciding he wanted to work with the producer Bob Clearmountain after his first album did nothing. He arranged a meeting. “I walked into the studio and I was waiting around and this guy pitched up on his bicycle. And it was Bob. ‘Hi Bob, I’m Bryan.’ He looked at me, perplexed. He said, ‘I’m just about to start a session, but come on up and let’s talk.’ So I went up there, played a couple songs for him. And he said, ‘Well, look, I really gotta go, I got stuff to do, but I’ll walk you downstairs.’ As we were going downstairs in the lift in walked Ian Hunter, who he was working with. And I was a big Mott the Hoople fan, so I was like, ‘Wow, Ian Hunter!’ Bob says, ‘Ian, this is… what’s your name again?’” But Clearmountain did work with Adams right through the Eighties, even if A&M rejected Adams’s plea to call his second album Bryan Adams Hasn’t Heard of You Either.

Adams’s Eighties and Nineties stardom was the kind that builds the foundations for a long career. Even now – he is 62 – if you search for books about him on Amazon, you will not find muckraking biographies. You will find scores of Bryan Adams 2022 calendars. To this day, lots of people want him hanging up in their kitchen (“I did not know that. It’s probably down to my love of food”). If you go to see him live, the crowd really does span all ages, from older people who bought Reckless first time around, to their grandkids, via twenty- and thirtysomethings to whom his songs have always been part of the cultural ether.

Part of that, he acknowledges, is down to the success of “I Do It for You”. He suggests there are songs that appeal to people who otherwise don’t like music. “That song was one of those songs. It appealed to people who never buy records. That song was big, everywhere, to the point that though some people didn’t understand what was being said in the song – people from other languages and cultures – they got the emotion of the song. The lyric is quite simple in its sentiment, but it was a sentiment that went around the globe. It was all-pervasive.”

I mention that between “I Do It for You” entering the charts in June 1991 and leaving them in December of that year, I graduated from university, got dumped by the woman I loved, went to graduate school, dropped out of graduate school, had my first anxiety episodes, then found out my father had terminal cancer. How did his life change in the same period?

He laughs. “I was on tour. People were always saying, ‘You’re Number One in England,’ but I wasn’t around to witness it. I was playing gigs, non-stop. I was on tour, literally, for four years. So the way it changed was suddenly, I was playing a lot more places, to much bigger crowds. And for a lot longer tours. I don’t suppose I ever really got to enjoy the surreal aspect of being No 1 for four months. I was only told about it. And I remember, there was a joke at the time about Terry Waite [the British envoy who was held captive in Beirut for almost five years]. And how the first thing he said after he was released as a hostage was, ‘Is Bryan Adams still No 1?’”

Is it possible to write a song so universal deliberately? He says yes, but only because he was working with the legendarily meticulous songwriter/producer Robert John “Mutt” Lange, the man responsible for huge hit albums such as AC/DC’s Back in Black, Def Leppard’s Hysteria and Shania Twain’s Come On Over. “If he’s going to get involved in you, and in your work, he wants it to be at a certain level. That’s why you hear stories about him working really hard and pushing people hard. Because he wants to get the best out of you. He only works with certain people because he sees something in himself that he can add to it. We got on famously from day one. And we’re still working together. I have to say that I have the same infinite awe of his talent. Because he can take my little idea and turn it into something quite epic.”

People start looking at you different, talking to you different. There’s no handbook for any of this

Lange returned to help Adams work on his 15th studio album, So Happy It Hurts, albeit Covid meant he had to record everything himself. It’s an amiable record – there are nods to Buddy Holly, as well as the heartland rock that’s still the basis of Adams’s musical identity, even though he has lived in London for donkey’s years now. One effect of his being so consistent is that his music sounds timeless, untethered to time and place in the way fleeting fashions are. He says he and his on-off writing partner Jim Vallance were always aiming for that. “We relied on the test of time. We hoped that things would continue to have a life beyond release days.”

And they did. Adams notes that the song “Summer of ’69” (“I only ever wrote that title because it made me laugh”) was not a big hit in Europe when it was released as a single in 1985. The best part of a decade later, he got a call from his label. “They said, ‘Did you know “Summer of ’69” has just gone to No 1 in Holland?’ Even though the song had a little bit of a life in North America, it took 10 years for it to become well known. It never even hit the charts in the UK. And so perhaps there’s something about the songs that we write that just don’t necessarily have that instant appeal. But in the long term, they climb out of the wreckage.” (It’s now comfortably his most popular song, with more than 735 million streams on Spotify.)

You would not call Adams a soul-barer. Or even someone who pretends to bare his soul. Contrary to the outspoken image suggested by his infamous Instagram rant against “bat-eating, wet-market animal selling, virus-making greedy bastards” in China for causing Covid, he speaks softly and carefully. He is not a relaxed interviewee (though we are doing it via Zoom, he keeps his camera off). There are those who spill their souls to interviewers, and there are those who want interviewers to be their friends. Adams is neither of those: he always said he hadn’t been too fussed about being a rock star, and he certainly doesn’t act like one. The best way to put it, perhaps, is that he is careful. (He later apologised for that Instagram post, by the way.)

He gets marginally prickly when we talk about the hardest point in his career. He says it was after the runaway success of Reckless, but even then only in the vaguest of terms – “People start looking at you different, talking to you different. There’s no handbook for any of this.” I say I had thought he might have found the second half of the Nineties hard, when his album sales dropped precipitously in the US, never to recover, after the huge success of 1991’s Waking Up the Neighbours.

And that is where he takes umbrage. No, he insists, the two albums that followed were big hits in America. But they weren’t: 18 Till I Die reached 31, MTV Unplugged peaked at 88; in fact, just one of his albums since Waking Up the Neighbours – including live records and compilations – has reached the US top 30. But he’s not going to pick a fight. We politely move along. He doubts my facts, and suggests his real problems in the US came a little later, when his recording contract was sold, and he ended up on Interscope. He recalls a label executive coming to him with a big plan to make him big in America all over again. “And he goes, ‘We’re gonna do MTV Unplugged!’ I said, ‘Ah, yeah, that’s a really good idea. Except my last album was MTV Unplugged. I think the next time you come around, man, you should do your research.’”

Adams knows there’ll never be another “I Do It for You”. He knows nothing from So Happy It Hurts will get on Radio 1 (“People in radio stations don’t judge music by the song; they judge it by how old you are”). He understands his albums are, now, more an excuse for him to go out and fill the arenas all over again. He’s in control of his career now, and he’s content: he’s got his solo career, he’s got his photography, he’s got his Pretty Woman musical in the West End. “It’s taken me years to get to this point now,” he says, “but I’m quite happy I’ve got there.”

‘So Happy It Hurts’ is released on BMG Rights Management on 11 March

This article was amended on 22 August 2022. It previously stated that none of Adams’ albums since Waking Up The Neighbours reached the US Top 30, but his 1993 compilation So Far So Good reached number six.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks