Drugs, jealousy, Nazi costumes: The harrowing story of Brian Jones, forgotten founder of The Rolling Stones

Reckless, objectionable, a genius musician ravaged by drugs and consumed by self-loathing, the Brian Jones brought back to our screens by Nick Broomfield is a deeply tragic figure. Jim Farber speaks to the acclaimed documentary maker about the Rolling Stone whose life was painted black

Lately, The Rolling Stones have been everywhere. The 60th anniversary of the band’s formation has brought with it a crush of events over the past year, including a European tour, a studio album of fresh material (their first in 18 years), tons of commemorative merchandise and a round of fresh interviews.

Lost in all this looking back, however, is any significant mention of the man who started it all; the man who founded the band, who gave them their name, and who served as their first leader: Brian Jones. “Brian definitely should have gotten more recognition for the anniversary,” says Nick Broomfield, who has directed a new documentary called The Stones and Brian Jones. “No one could be more celebrated than Mick and Keith, and rightly so, but I don’t think they would have lost anything at this point by recognising Brian’s contribution.”

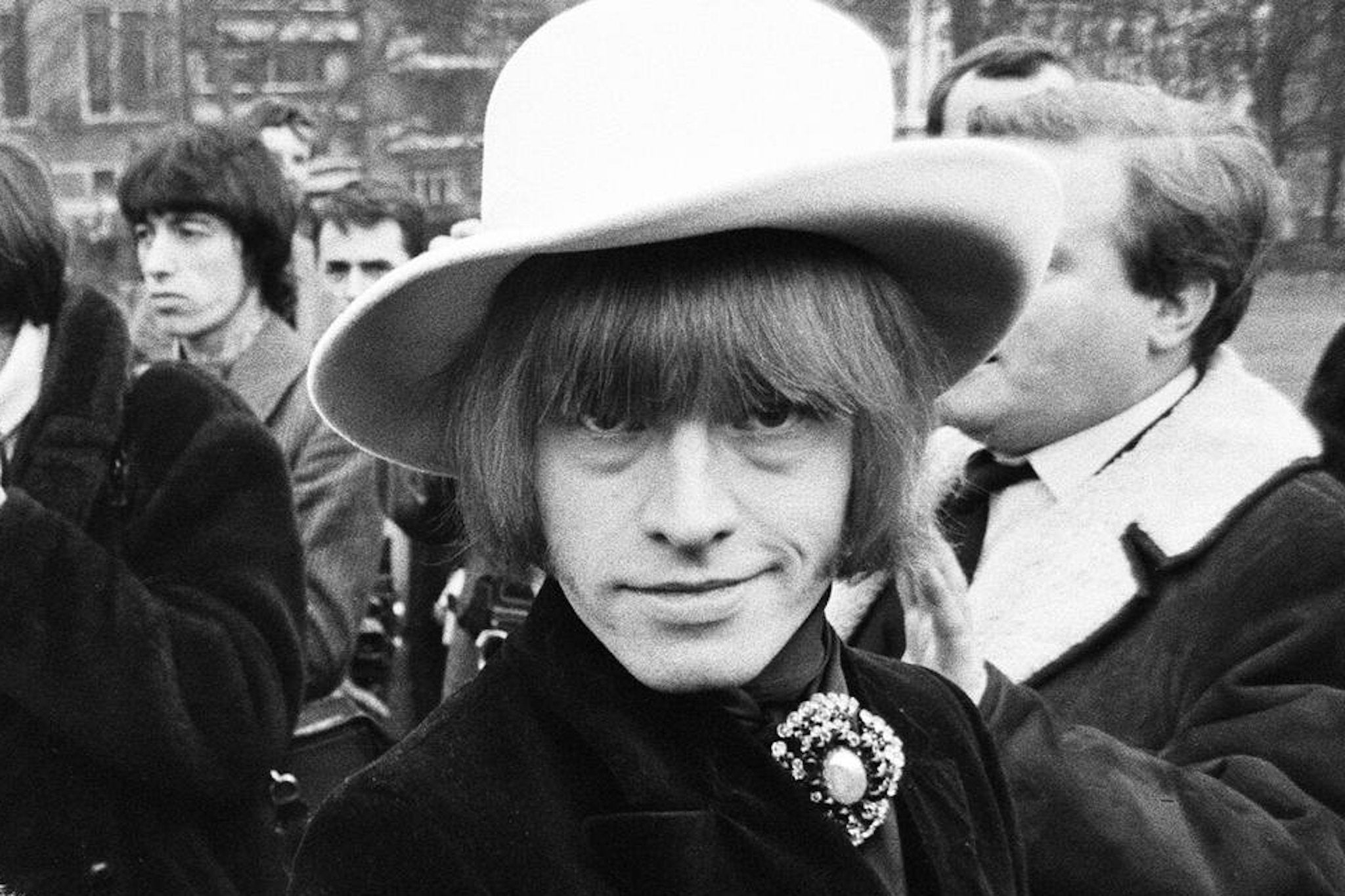

Broomfield’s film works overtime to make up for that. It presents Jones’s contribution as both crucial to the Stones’ character and corrosive to their dynamic. Together, that created a push-and-pull in his life that could barely be more dramatic. Initially the most popular member of the band, Jones wrestled with a depth of self-loathing that led to increasingly outlandish and dangerous behaviour escalating to his death at 27, mere weeks after he was thrown out of the band. Using a mix of fresh and vintage interviews, with everyone from Jones’s family to his many lovers and members of the Stones, the documentary presents a broad portrait that, perhaps by necessity, spends much of its time vacillating between the sad and the infuriating.

“Brian could be an incredibly difficult person,” Broomfield says. “He went out of his way to be objectionable sometimes, which is why a lot of people wrote him off. But I wanted to look beyond that to get some kind of understanding of where all that darkness that possessed him was emanating from.”

Apparently, much of it came from his haunted childhood. References to a troubled home life bookend the film, starting with a quote from frequent Stones chronicler Stanley Booth, who casts Jones as a casualty of the generational wars of the 1960s. “There was an enormous gap between the post-war generation’s view of the world and their parents’,” the director says. “It may be the biggest gap that has ever been. It affected Brian’s relationship with his parents profoundly.”

Another factor in their strained dynamic, and perhaps the most vexing issue within the Jones family, is left out entirely. When he was just 18 months old, his younger sister, Pamela, died of leukaemia, 11 days after she was born. “Brian always felt that his mother’s love went to the missing sister and not to him,” Broomfield says. “I spoke to one of his babysitters who said that when she was looking after Brian, he would pull out the family album because he wasn’t supposed to talk about his sister. The whole thing was very circumspect.” In the end, Broomfield chose not to mention Pamela in his film. “I couldn’t quite put my finger on that unstated, subterranean feeling in the family,” he says of his decision. “There was a hinterland of strangeness there.”

Other tensions are more directly expressed. Jones’s parents were deeply conservative and highly judgmental of their child – a harshness that existed in contrast to the families of the other Stones. “They all mucked in and cooked meals and were pleased that their kids were trying to do something [in music],” Broomfield says. Meanwhile, “Brian’s father was a highly educated mathematician who wanted his son to have a regular profession”. His mother, a classical pianist, “hated the blues, which Brian played all the time,” Broomfield says. “She viewed it as a degraded form of music.”

Jones’s obsession with the blues was to the detriment of everything else, including his studies, leading to his expulsion from school at 17. That same year, he got his girlfriend pregnant and his parents threw him out of the house. (The child was soon put up for adoption.) The pregnancy “must have been a nightmare for his Bible-punching parents,” Broomfield says. “He chose the very thing that would upset them most.”

And he kept on doing so. Jones’s teen girlfriend was the first of five women who became pregnant by him in as many years, a consequence of a time before the contraceptive pill. Difficult as such events may have been for Jones, they contributed to a character that, Broomfield says, “embodied the bad boy spirit of the Stones more than any other member. He had illegitimate children everywhere. He got kicked out of every school he ever attended. His parents couldn’t abide him.” Broomfield adds, “You can see why Brian identified with the protest of the blues. It became his salvation.” Hooked on Mandrax.

Their new manager [Andrew Loog Oldham] set the members against each other. He didn’t like Brian at all

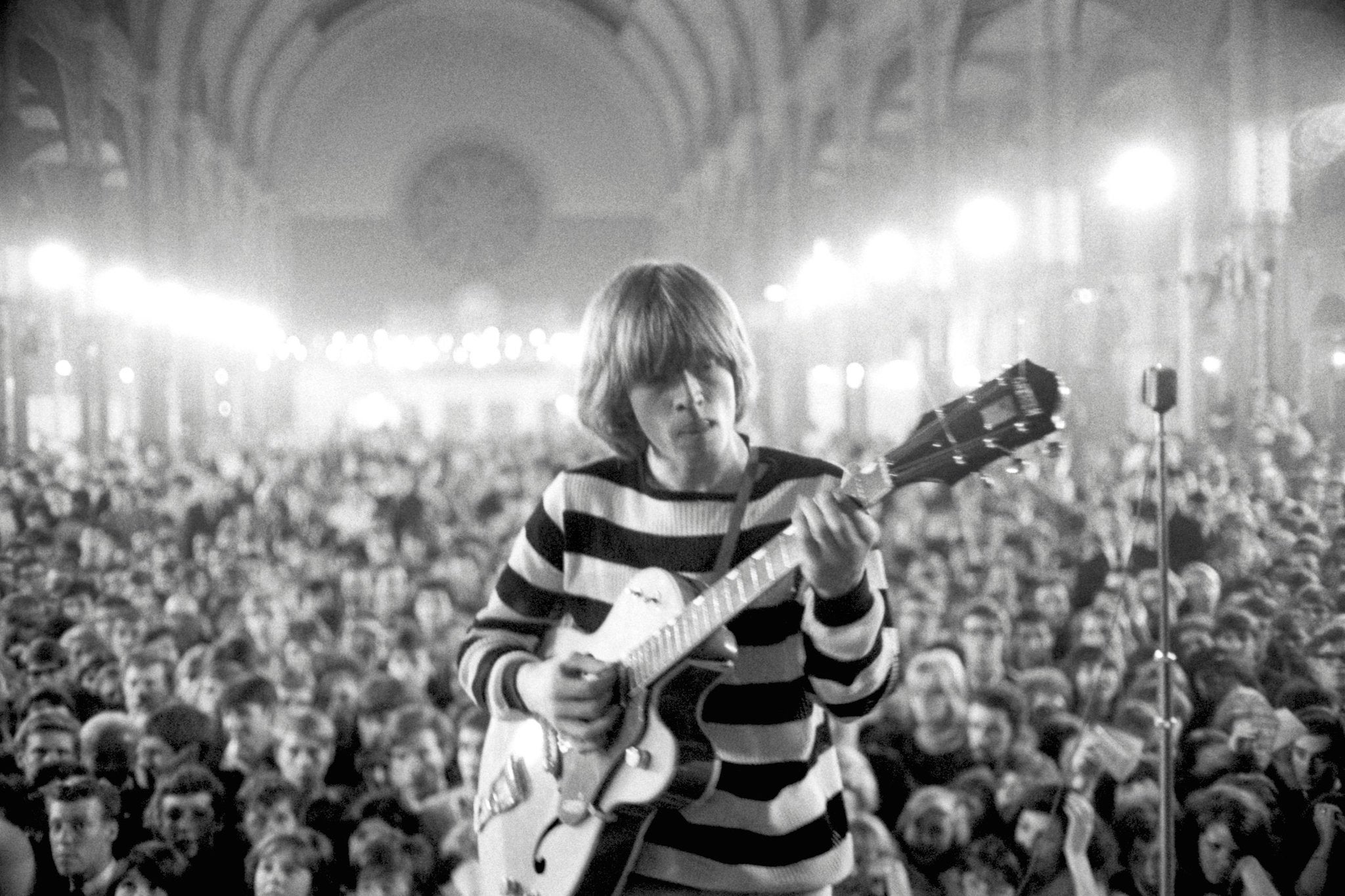

He studied the genre night and day, playing his favourite blues records over and over until he could get every riff down right. While still a teen, Jones moved to London where he began playing with other musicians on the rhythm and blues scene, including Alexis Korner and Jack Bruce. In May 1962, he placed an ad in Jazz News seeking players to form a new R&B group. That line-up eventually coalesced into The Rolling Stones, which took its name from a Muddy Waters song. Once the band began to gain traction, Jones drew the most fan mail despite the fact that Jagger was their frontman. At that time, he also had the closest rapport with Richards. The two guitarists spent endless hours perfecting the interplay between them, a style they called “weaving”. “It’s a specific discipline to learn to play that way,” Broomfield says. “It requires incredible timing and precision. It made for a very creative relationship between Brian and Keith.”

For his part, Jones brought a cool slide guitar style to the band, evident on songs like Willie Dixon’s “Little Red Rooster” (a No 1 hit in the UK) and Bo Diddley’s “Mona”. Soon it became apparent, however, that Jagger had far more focus. “He was the force that was moving things forward,” the director says. “Mick was the organised one.” He was also physically stronger. While Jones suffered from asthma since childhood, “Mick was like an Olympic athlete who had bags of energy,” Broomfield says.

Jones was weaker psychologically too, putting him at a great disadvantage when the power dynamics within the band shifted. Pushing the shift was Andrew Loog Oldham, their new manager. “He set the members against each other,” Broomfield says. “He didn’t like Brian at all.” Instead, he obsessed over Jagger and Richards, insisting that the pair do all the interviews while keeping Jones in the shadows. Oldham also pushed the group to ditch their limiting role as blues acolytes, an identity that Jones had conceived, to write original songs, a skill Jones notably lacked. “Brian was very jealous of the outstanding contribution of Mick and Keith with those songs,” Broomfield says. “He couldn’t in any way compete.”

His jealousy played out in spiteful ways. When Richards came up with the classic riff for “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” Jones called it “vulgar and cheap”. “Brian couldn’t acknowledge that what they had done was amazing,” Broomfield says. Though unable to write formal songs, Jones began to make increasingly important contributions to the band’s evolving sound, as well as to their image. He was “the first to start wearing mascara and women’s clothes,” Broomfield says, “the first to play with androgyny.”

Anita Pallenberg brought a worldly vision to the band but she was also terrifying. You never knew who she was going to pick on next

He also brought a wealth of new instruments to the band and played them with aplomb, smoothing the band’s move into psychedelic exotica in the mid-Sixties. “He could pick up any instrument and within five minutes use it in some remarkable way,” Broomfield says. Jones brought a marimba to “Under My Thumb”, a recorder to “Ruby Tuesday”, a dulcimer to “Lady Jane”, a sax to “Dandelion”, and a mellotron to songs like “She’s A Rainbow” and “2000 Light Years from Home”. “Brian’s contributions really made those songs,” says Broomfield.

His influence was amplified by his relationship with It-girl Anita Pallenberg, the German-Italian model, actor and provocateur who, at the time, out-hipped even the Stones. “Anita brought a worldly vision to the band,” Broomfield says. She was also terrifying. “You never knew who she was going to pick on next.” Pallenberg’s snarky character only further enabled Jones’s cruel and contrary sides. One photo from the time depicts the couple dressed up in Nazi uniforms, a swastika armband wrapped around Jones’s bicep. Their relationship also became physically abusive on both sides, with Pallenberg emerging as the more formidable one, Broomfield says.

In a legendary turn of events, Pallenberg wound up leaving Jones for Richards, a brutal blow that epitomises the litany of losses in Jones’s life. To cope, he increased his drug use with abandon, which only made things worse. In fact, Jones was the prime druggy in the band at the time – not Richards, who later gained that reputation. More, he boasted about it in the press, which, Jagger believed, led to the infamous 1967 bust at Redlands that threatened him and Richards with serious jail time. “It finished off their relationship completely,” the director says.

Jones’s extreme drug use, centred on the sedative Mandrax, made it nearly impossible for him to perform. During the filming of the Stones’ 1968 TV special, Rock and Roll Circus, all he could manage were some shakes of the maracas. Footage from the special shows him looking dazed, bloated, and far older than his 27 years. According to Broomfield, Jones’s drug problem undermined another important project.

I didn’t want to give the conspiracy theories around Brian’s death any credence

In the summer of ’68, he flew to Morocco to record the local musicians of Joujouka for an album later recognised as one of the first examples of a Western musician presenting traditional sounds from the so-called third world. The album, billed as Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka, was heralded as a groundbreaking work that presaged later worldly projects by artists from Peter Gabriel to Paul Simon. Oddly, Broomfield does not mention the album in his film, a decision he made, he says, because the project’s sound engineer told him that Jones was passed out on the floor almost the entire time. “Brian may have had the inspiration to go to Morocco,” Broomfield says, “but he couldn’t follow through.”

Jones’s deteriorating physical state led directly to the Stones’ decision to fire him the following June. By the next month, he was dead. Jones had drowned in the pool at his home in Hartfield, East Sussex, after taking heavy sedatives. The coroner ruled it “death by misadventure”. Broomfield’s film makes a point not to delve into the later conspiracy theories that Jones had been murdered. “I didn’t want to give them any credence,” he says.

Instead, Broomfield ends his film with an emotional flourish. Linda Lawrence, one of Jones’s main girlfriends and mother to one of his five children, reads aloud a letter written by the musician’s father, which was sent to Jones about a year before his death. Lawrence discovered it in a trunk filled with Jones’s effects that came to her. The letter, which Jones never opened, finds his father expressing profound guilt for not understanding his son. “I can’t imagine how it must have felt for him to write that admission of failure – basically, to ask for forgiveness from his child,” Broomfield says. “It must be the hardest letter for a parent to write.”

Tragic as such events may be, Broomfield believes there’s more to Jones’s story than sadness. “He was a brilliant person who had the ability to introduce sounds that hadn’t been heard before,” he says. “Who knows? If Brian had lived at a different time, maybe he would have gone into some kind of [rehabilitation] programme that didn’t exist then. Given his talent, you can imagine what could have happened if things had been just a little bit different.”

‘The Stones and Brian Jones’ will receive a one-night-only theatrical screening on 7 November before it is digitally released on 17 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments