Brecht has lost none of his bite: How the message from a 1920s opera resonates today

The critique of consumerism in the 1920s opera ‘Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’ is particularly relevant in the 21st century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A remarkable opera called Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny first took seed in the mind of its creators, the composer Kurt Weill and the playwright Bertolt Brecht, 88 years ago. Its story is so contemporary, though, that it could almost have been written yesterday. It charts the creation, supposedly in America, of a city of pleasure with no history and no moral compass – and its destruction in a morass of consumerist malaise and addiction, with inhabitants put to death for the crime of having no money. The whole place ultimately goes up in flames.

Its famous numbers – including “Alabama Song”, with the refrain “Oh, show us the way to the next whisky bar” – are among the best-known of their time. Yet it has never before been staged at the Royal Opera House. Its first production there, directed by John Fulljames with an all-star cast including the bass Sir Willard White and the mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, opens tomorrow.

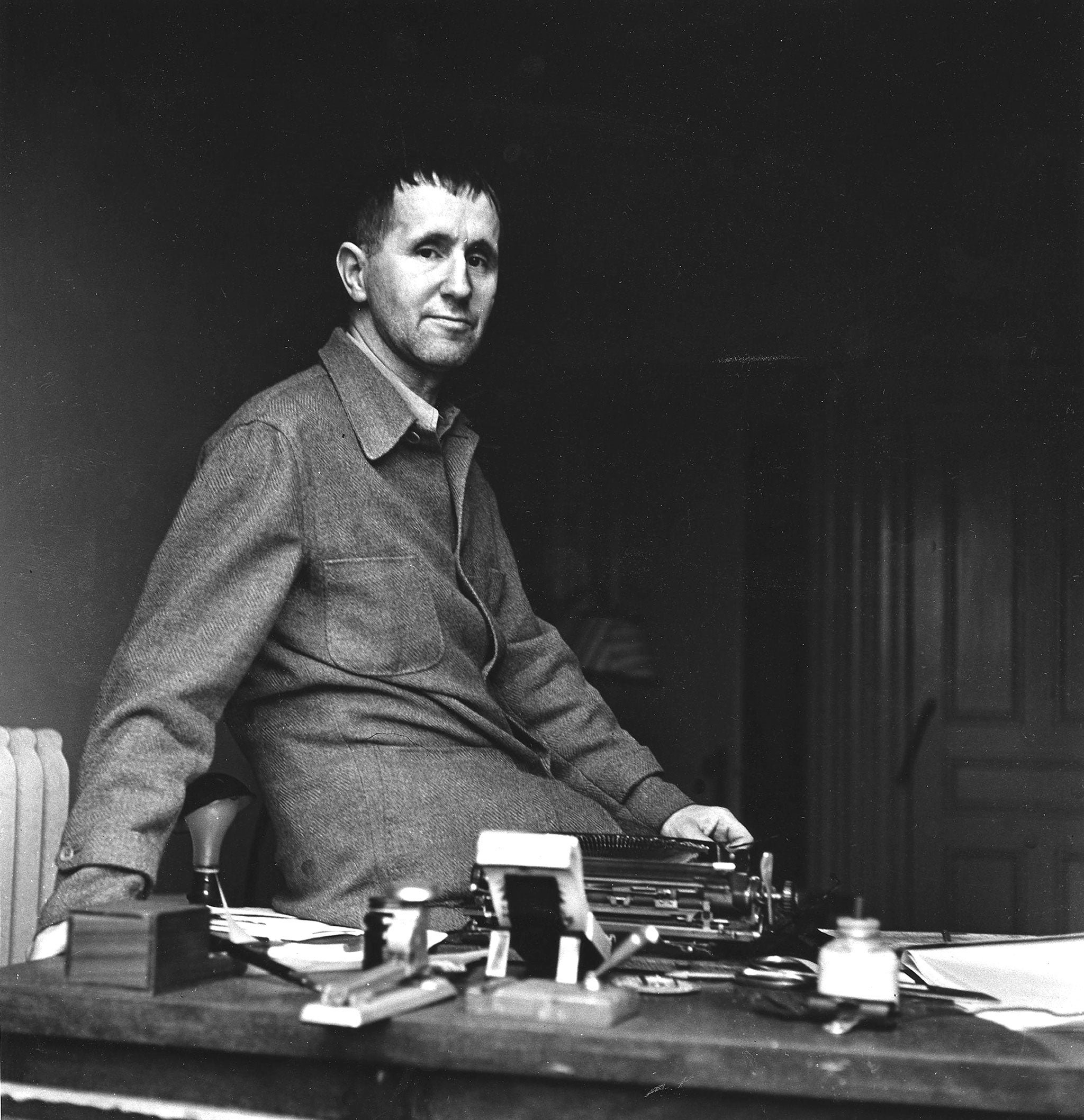

Born in the boom of 1927, completed in the bust of 1929 and first staged in Leipzig in 1930 at a time when Europe was in ferment and the Nazis were on the rise, this opera has a bite as strong as its bark – thanks to the brief meeting of minds between two of the most distinctive artists of their day. For Brecht and Weill, it was a collaboration as stormy as it was intense.

It all began when the 27-year-old Weill, searching for a libretto for a short opera for Baden-Baden, read a new collection of poetry by a young dramatist he had encountered earlier that year in the radio studio of the Funk-Stunde Berlin. The volume included five poems entitled Mahagonny Songs. Inspired, Weill found a way to meet Brecht and the pair quickly decided that their mutual aspirations would make them a good team.

Weill had risen to prominence as a powerful voice among the expressionist, atonal avant-garde of the 1920s. Brecht, born in Augsburg and two years Weill’s senior, is described by the librettist Jeremy Sams – who has made a new translation of the opera for this production – as “probably the greatest poet-dramatist since Goethe”. Both writer and composer were keen to revolutionise what they saw as a clapped-out tradition of opera in desperate need of a rethink.

Jeremy Sams comments that despite the artistic rewards of Brecht and Weill’s partnership, their combination was in other ways “toxic”. During the few years they worked together, they spurred one another on: “You just think ‘Lennon and McCartney’,” says Sams. “They’re in their twenties, each raising the other’s game, each thinking his way of doing things is influencing the other.

“But Brecht has a problem,” he continues. “He thinks he’s the best, but he knows that Weill is better than he is, and he absolutely hates it. They clash all the time. In the Mahagonny rehearsals it’s ghastly – Brecht is saying ‘Why are you spoiling my beautiful words?’, Weill is saying ‘Why are you spoiling my music?’ – and each is convinced that he’s ruling the roost himself.

That was only part of the trouble. “There are other massive issues between them,” Sams adds. “Some are financial. Then Brecht is a bully and a user; Weill is a much nicer guy. They’re perpetually fighting. What we have is a wonderful record of two people who both think they’re right. And the work comes out that way.”

John Fulljames, director of the ROH production, also points to the opera’s unusual balance of music and words: “Opera is generally music-led, with the storytelling happening through music, but here the balance is more equal between the two,” he says. “There’s no contradiction between text and music, and we want that to be heard loudly by the audience. I think the bite of the text encourages you to understand that the more sentimental music is intended ironically. It’s never sentimental or escapist.”

He has commissioned a new translation from Sams, he adds, not least to emphasise the contemporary and European qualities of the text. “There’s a danger that the existing translations deliver the piece as an American opera and I don’t think it’s anything of the sort,” he says. “This is a European work written about a fantasy of America – Amerika with a K, if you like. It is a piece which emerges from Europeans, about a European world, and it’s American only because America was the land of the future at the beginning of the 20th century. If you were writing such a piece now, you’d probably set it in Dubai or Shanghai.”

For Weill and Brecht, though, it was not the new world that went up in flames, but the old one. Weill, banned by the Nazis after Hitler took power in 1933, escaped from Germany, going first to Paris and then in 1935 to New York, where he reinvented himself as a composer of Broadway musicals, including One Touch of Venus and Lady in the Dark.

Brecht, too, fled Germany and tried exile in a variety of different countries before moving to the US in 1941. There, though, he was blacklisted by Hollywood for his Marxist sympathies.He moved back to Europe in 1947 and eventually settled in East Berlin. Following the East German uprising in 1953, he wrote a poem, “The Solution”, that concluded: “Would it not be easier/ In that case for the government/ To dissolve the people/ And elect another?” It was palpably the same sensibility at work as in Mahagonny – but within a different vision of societal downfall.

The message of Mahagonny – moral rather than political – is deeply contemporary, yet possesses the timelessness of a fable. Emblematic of its own day, it is universal enough to be emblematic of ours as well. Before asking the way to the next whisky bar, anyone who doubts opera’s continuing relevance to our world should go and see it.

‘Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’, Royal Opera House, London WC2 (020 7304 4000) tomorrow to 4 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments