Brahms: The Hungarian Connection explores the composer's love of folk music from the country

Meet the clarinettist showcasing the composer’s Magyar magic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

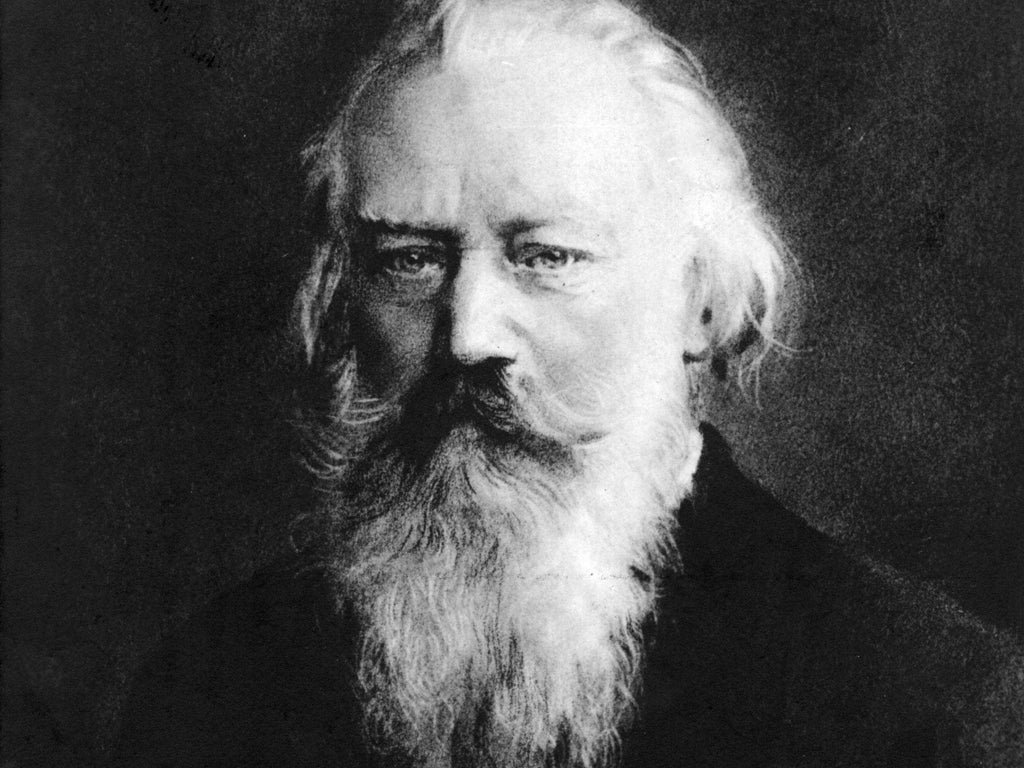

Your support makes all the difference.Born in Hamburg in 1833, Johannes Brahms was raised on a diet of Bach and Beethoven. But despite the lessons he absorbed from his scores of those masters, he craved a little more spice. That he found in Hungarian folk music, according to clarinettist Andreas Ottensamer, whose new album explores the composer’s lifelong obsession with the music of the Magyars.

Brahms: The Hungarian Connection features two of Brahms’s popular Hungarian Dances, as well as his Clarinet Quintet, performed alongside works by Budapest-born composer Léo Weiner and arrangements of other traditional tunes. The 26-year-old Ottensamer knows exactly how these things should sound; growing up in Vienna, he was raised by an Austrian father and a Hungarian mother, who “used to sing Hungarian songs to me when I was little”, he says. Those lullabies clearly stuck.

One of the leading clarinettists working today, Ottensamer has followed another family tradition, as both his dad and his older brother are principal clarinettists with the Vienna Philharmonic. It was as a deputy there (and as a member of the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra) that Andreas cut his teeth, but in 2011, he strode out on his own, becoming one of the youngest-ever members of the Berlin Philharmonic. Two years later, he became the first clarinettist to earn an exclusive contract with top classical label Deutsche Grammophon. This, his second album, offers “a very personal approach to my experiences and musical life with Brahms”, he says.

For years it was unfairly presumed that Brahms had merely added a dash of ersatz Magyar magic to his Hungarian Dances, skipping the requisite fieldwork. And yet by comparing the earliest transcriptions of those tunes in Brahms’s notebooks with the original folk material, Ottensamer has come to realise that this is music “of the deepest Hungarian origin”.

Brahms was first exposed to this evocative folk culture in Hamburg in the early 1850s, when the city’s port became a key exit point for people fleeing revolutionary Europe. The pianist and composer was an habitué of the city’s dance halls and taverns and, galvanised by his recitals with Hungarian violinist Eduard Remenyi, he came to know and love the lilt and rhythms of the csardas and verbunkos.

On moving to Vienna, then capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Brahms started to write down his Hungarian Dances, promptly selling thousands of copies worldwide. The first piece from his collection of 21 dances, based on Miska Borzo’s Isteni Csardas, is a highlight of the album, thanks to cellist Stephan Koncz’s vivacious arrangement, as Ottensamer weaves his way through a potent combination of string quintet and cimbalom (a kind of dulcimer struck with hammers). It certainly sounds more authentic than Brahms’s overly upholstered orchestrations. Getting underneath those plush trappings, Ottensamer and his team have revealed the true spirit of this music.

With its many echoes and allusions, the album offers a clear bridge between these dances and the 1891 Clarinet Quintet at the start of the CD. Return to that monumental work after listening to the rest and you will hear a slow hallgato (a traditional Hungarian song with verses) within the second movement, typified by a rhythmically free, almost improvisatory style. In other places, Ottensamer says, “it may just be one bar, but the way Brahms combines rhythms or the way he uses phrasing is thoroughly Hungarian”.

After all, he lived in multi-ethnic, multicultural times, when musical influences were acquired by cross-pollination: just as the Vienna-based Brahms was influenced by the diverse peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so Hungarian gypsy bands were inspired by the music of Vienna. Even the quintessentially Austrian Johann Strauss II, one of Brahms’s closest friends, had Hungarian ancestry. The dissolution of the Empire in 1918 and the arrival of the Iron Curtain in 1945 divided these two cultures, but a kinship endures to this day.

The Hungarian Connection is a tribute to that camaraderie and, in trying to capture its essence, Ottensamer “had a kind of jam session” with Koncz and his younger violinist brother Christoph, improvising on the themes Brahms heard 150 years ago. Ottensamer then brought together “a real dream team” for the recording, with the Koncz brothers performing alongside violinist Leonidas Kavakos and viola player Antoine Tamestit, as well as Hungarians Odon Racz and Oskar Okros on bass and cimbalom and Serbian accordionist Predrag Tomic. “They’re all superb musicians, amazing soloists and chamber musicians, but also great friends.”

Friendship was intrinsic to Brahms’s music-making too. His time on the road with Remenyi was clearly inspirational and, later in life, he struck up a significant friendship with the clarinettist Richard Muhlfeld, prompting the creation of several works in the composer’s twilight years. Brahms had declared his life’s work over, but was so enthused by Muhlfeld’s playing that he not only wrote the Clarinet Quintet for him, but also a trio and two sonatas, all characterised by a feeling of affection and, Ottensamer claims, “that typically Hungarian idiom”.

“These pieces are so special nowadays because they were so special back then. Brahms had such a strong connection to the instrument.” Acknowledging his debt to Muhlfeld, the elderly Brahms gave him all the fees from their performances and the manuscripts of both clarinet sonatas after publication.

The singularity of that relationship tells. “The way Brahms writes”, Ottensamer says, “putting the most beautiful possibilities of the instrument in the spotlight, demonstrates that he must have spent a lot of time with Mühlfeld; it is the only reason we have these treasures”. Returning to the grass roots of Brahms’s musical language, Ottensamer has shown off those treasures in a persuasive new light.

‘Brahms: The Hungarian Connection’ is out now on Deutsche Grammophon/Mercury Classics (www.andreasottensamer.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments