Bob Marley and me: Photographer Dennis Morris on capturing the reggae star at his peak

Morris reveals his memories of the man behind the all too short musical career

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He is one of the most-photographed men in the world, whose dreadlocked visage adorns walls everywhere in the form of posters. But what was it like getting near enough to take a close-up of the reggae star? Dennis Morris shares insights into the legend.

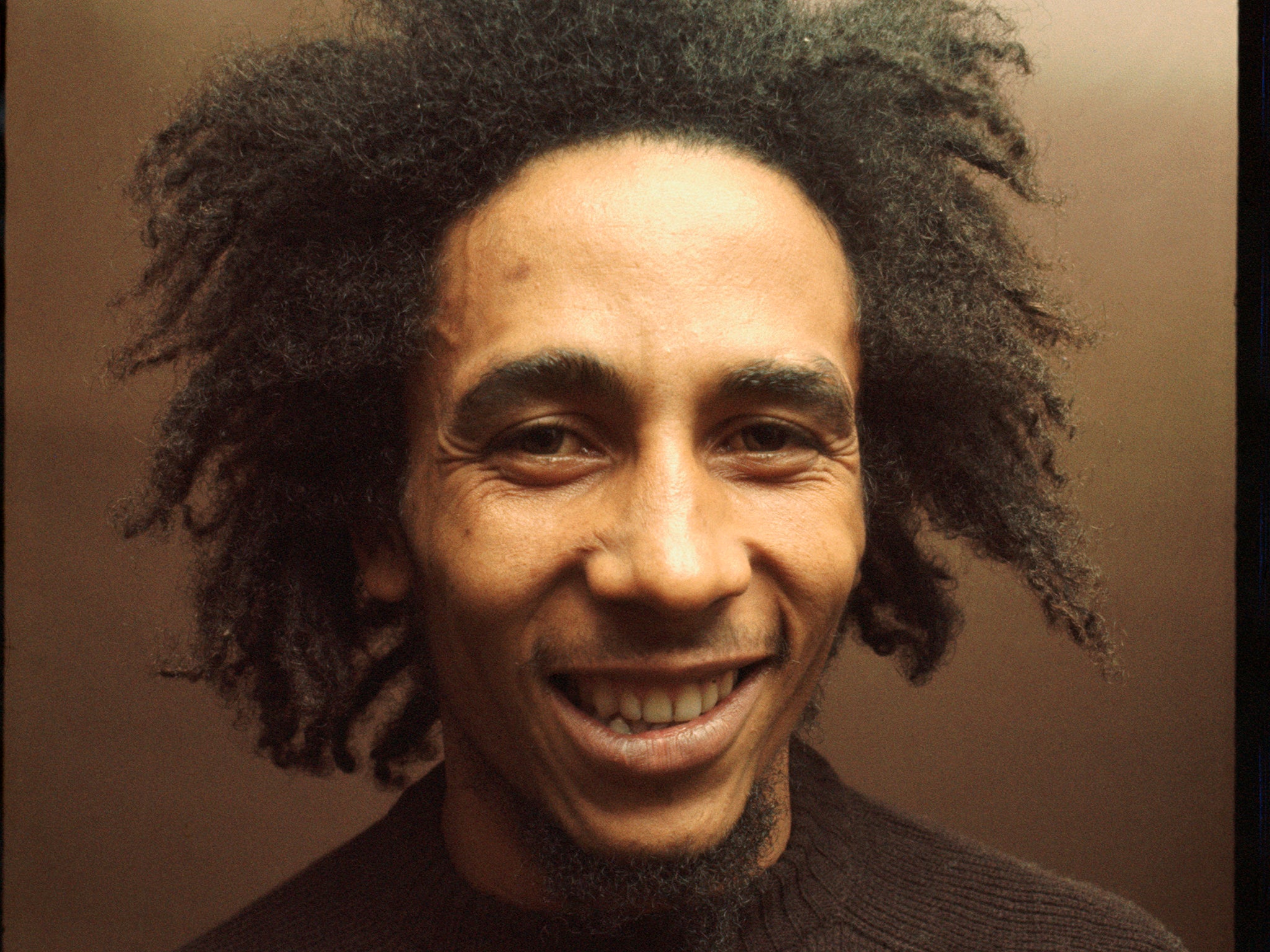

Leeds, 1974 (above)

That’s from that first tour; you can tell by the length of his locks, they’re quite short.

I had known him just for a few days when that was taken. My relationship with Bob started with his music. It was very popular in the West Indian community, everyone was talking about this new music giant and I read he was coming to do his first tour of England. I was at school in London and one of his gigs was at a club called the Speakeasy club on Great Marlborough Street. So I went there during the day and when I saw him, I asked: “Can I take your picture?” and he said “Yeah man, come in”. He was fascinated by me and asked what it was like to be a young black kid in England and I asked him about his life. From the moment I saw him I knew I was in the presence of something very special and I knew I had to be a part of it in whatever form. He gave me such confidence. When I said I wanted to be a photographer, he said, “You are a photographer”, and then I knew I could do it because the man told me. The next day I hopped on the transit van with the band and that’s where it all started.

I originally wanted to be a reportage photographer. I wanted to be Donald McCullin, Tim Page, Gordon Parks. Parks was a big influence, he was the first black photographer to work for Life magazine and Donald McCullin did those images of poverty in Harlem. So I took that technique into rock photography. Before that it was mainly posed shots: stand against the wall and click, but my photos of Bob were all studies, taken talking to each other in hotel rooms or wherever, none of them were set up.

It was easy to get those comfortable shots because he really took to me and vice versa. He asked a lot about London, what the situation was like. For me it was great. I was 16, 17, I knew to be the kind of photographer I wanted to be I was looking for those situations to get close to people, it was the excitement of it. I think I caught many great moments. When people look at these portraits now they say it feels like he’s still around, there’s still so much life in them.

Cheeky Bob

I call that the “cheeky Bob”, he’s got such a cheeky expression. That’s the look he used to get the 16 children that he has. He looked after all of them, he had bank accounts for all of them, but it only came out after he died that he had 16 kids because he was a very private person. Some people might think he was a womaniser but whenever I witnessed it they all wanted his babies; there wasn’t a woman in the room who didn’t want his babies. It wasn’t like he chatted them up but women just fell in love with him and all the men wanted to speak to him. He really was a very special person.

Ping pong match, Marley’s house on Hope Road in Kingston, Jamaica

This is in his house in Jamaica, as you can see he’s a very fit man. Girls love that picture for obvious reasons. His first love was football but he liked table tennis too. He supported Tottenham. I’m not sure why, he just liked Tottenham.

Peter Tosh and Bob Marley rehearsing, 1974

The person with the white woolly hat, it was him, Bob and Bunny Wailer and that was the full line-up at the time. The thing I remember about the early tour days was he was only known in the West Indian community and then when Island Records signed him he was trying to break into the rock circuit and maybe only 20 people would turn up to his gigs. But as soon as he walked out on stage, he walked out as though the gig was sold out. He was just so full of confidence, I’ve never seen so much confidence, especially as he was a young black guy; it was unbelievable. To him, there was nothing that was impossible and he knew he wanted to get a spiritual message across and he succeeded. I’ve been to all kinds of places and everywhere you go there are places with his music playing. He meant so much to everyone.

House on the King’s Road, Chelsea, 1978

He was on tour and had just come back to his house and was just relaxing. I remember it was a massive house. The entire band and his cook were staying there, it was like an open house really. The place was over-run with Rastas and devotees would come by just to chat and talk and meditate. I don’t imagine the King’s Road had seen anything like it then, although there were more punks and Rastas around then.

By then he had his own cook to do his Ital (Rastafari vegetarian food). Vegetarian and vegan Rastas don’t eat salt and so the food has lots of pepper to make up for the lack of salt. It was great food! She was a proper Jamaican cook doing yam and bananas and dumplings. I remember it was very hot. When he first started touring he hated the food, and the only thing close to Ital would be Indian vegetarian. They weren’t too keen on that.

Paris 1979

This was taken at the height of his fame. Bob Marley and the Wailers really took off in 1977 and by 1981, aged 36, he died. It was just four years. It was a very short time.

Fame didn’t change him at all, the only thing was it meant he had more access to money to help people in Jamaica, and he was able to deliver the message on a wider scale. He was always dressed in denim; he wasn’t flamboyant in the way he dressed. The only flashy thing was he was the first Jamaican to drive a BMW (because it stood for Bob Marley and the Wailers) and then after that, any black man with money bought a BMW and it drove up sales. That was the extent of his influence.

At the height of his power, he was putting more revenue into Jamaica than the Jamaican population. Everyone wanted to see where this man came from, and it became a huge tourist destination, it became like a pilgrimage for people, like when the Beatles went to India, it became a hippy place, not just for the elite.

Dennis Morris will be talking on 30 April as part of Always Print the Myth: PR and the Modern Age, which runs to 9 May. Dennis Morris’s work also appears as part of the Staying Power: Photographs of Black British Experience 1950s-1990s’ until 24 May. Both shows are at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London SW7 (020 7942 2000)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments