Bob Dylan: The myths of the singer-songwriter's electric debut at the Newport Folk Festival

According to legend, his set 50 years ago was booed by sections of the audience

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

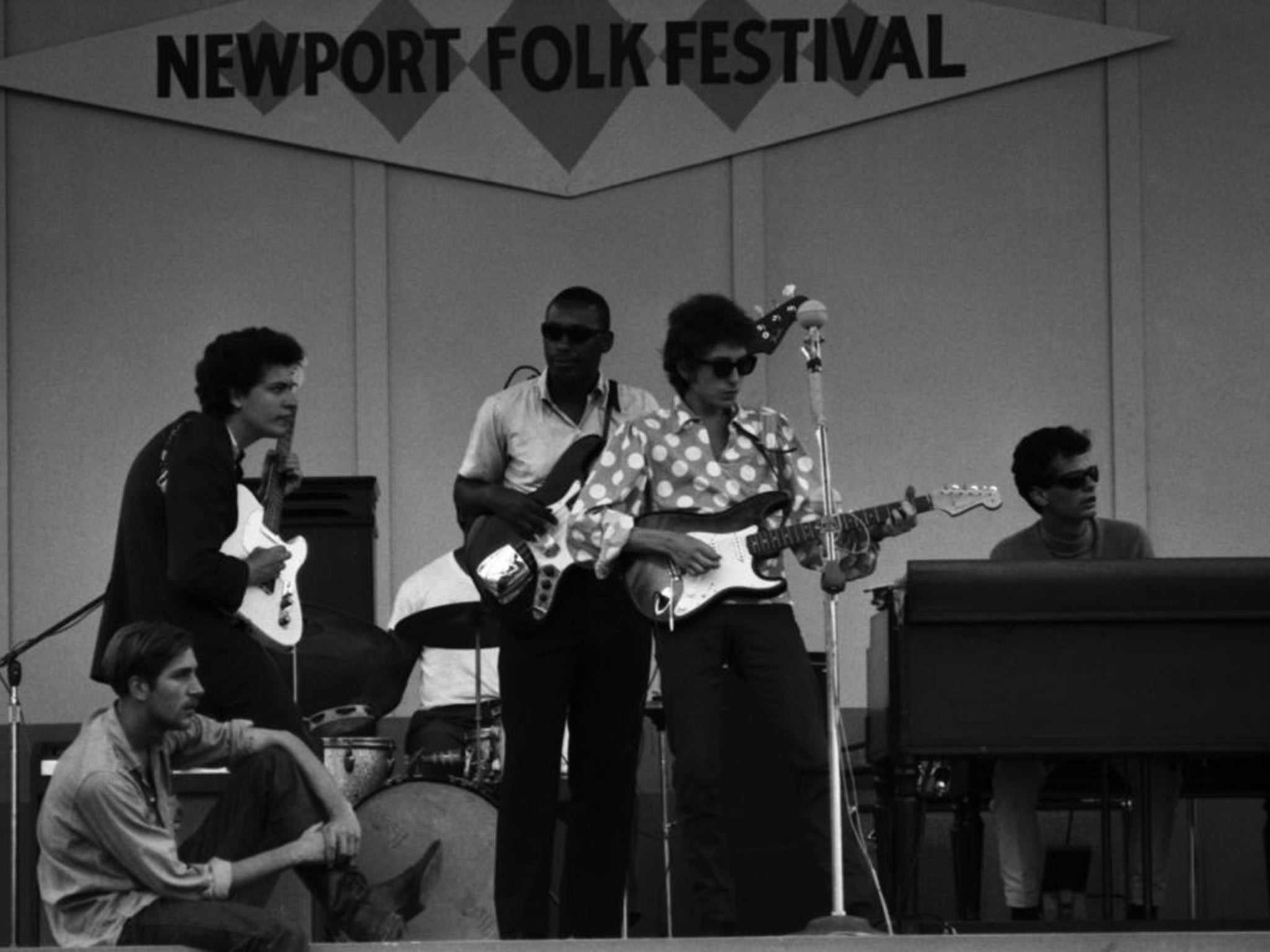

Your support makes all the difference.Fifty years ago today, Bob Dylan walked on stage at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island with a Fender Stratocaster. According to legend, his brief set – three songs including “Like a Rolling Stone”, the six-minute-plus masterwork he had released as a single just five days earlier – was booed by sections of the audience who were appalled that the “voice of a generation” had ditched the raw authenticity of acoustic music for the crass, commercial thrills of an amplified rock ’n’ roll band.

Dylan “electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other”, one critic wrote at the time. For Robert Polito, writing in The New York Times, the events of 25 July 1965 were nothing less than “the cataclysmic finish of the folk movement”.

Al Kooper, the man playing the Hammond organ in Dylan’s hastily assembled band that day, remembers things a little differently. The short set was underwhelming and the much-discussed booing, well, that didn’t happen, he tells The Independent on Sunday. “It’s bullshit,” he growls. “It’s journalistic hoo-ha.”

If there was any discontent in the crowd that day it was because Dylan left the stage after only 15 minutes. Why? Because the band he’d put together in haste at a mansion in Newport the previous night was struggling to play his songs, says 71-year-old Kooper.

“If you travelled from god knows where and paid god knows what to see Bob Dylan, and sat through music you didn’t relate to for three days, and then he came out and only played for 15 minutes, what would you have done?” says Kooper. He confirms that Dylan and the band did get booed at the concerts they played after Newport, but only, he argues, because the “Dylan goes electric” myth was putting down roots and “that’s what the journalists told the lemmings to do…”

The limitations of Dylan’s hastily assembled band emerged as soon as they began to rehearse on the Saturday evening. Kooper and harmonica player Paul Butterfield were well attuned to Dylan’s way of working, having played on the recording session that produced “Like a Rolling Stone”. But bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay were out of their depth, says Kooper.

“They only played blues music and struggled,” he says. “After 10 hours of rehearsals, the band could only get three songs together: ‘Maggie’s Farm’, ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and ‘Phantom Engineer’, an early version of ‘It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry’.”

The concert was as shambolic as the impromptu rehearsal, according to Kooper. Sandwiched between two traditional folk acts – banjo player Cousin Emmy and the Georgia Sea Island Singers – the band’s breakneck electric performance “wasn’t particularly good”.

When the last note rang out, Dylan took a bow and left the stage. He was met by an agitated master of ceremonies, Peter Yarrow, who told the singer: “Bob, you can’t leave them like this.” Dylan borrowed Yarrow’s acoustic guitar, returned to the stage (where he borrowed a harmonica from the audience) and sang “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”.

“I think that was the most galvanising moment of the whole evening,” says Kooper. “Whatever he was saying, it was a great moment.”

Kooper played two more gigs after Newport, then quit the band because the tour was scheduled to visit Dallas, where President Kennedy had been assassinated two years earlier. “I figured, they killed Kennedy there – what chance do we have?”

Kooper, who went on to play and record with a who’s who of bands – including the Rolling Stones, Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience – as well forming Blood Sweat & Tears, says rock’s myth-making has been a regular source of upset.“I have watched this happen countless times – times when I was in the room, but the story was never told correctly.”

For example? “Well, the Brill Building, for a start. Many of the indelible pop songs routinely held up as examples of ‘The Brill Building Sound’ were actually written at another building, 1650 Broadway.

“There are scores more like that,” he says. “It’s sad to me that history has been corrupted and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

The idea that parts of the crowd were horrified and booed when Dylan went electric is “already etched in stone”. “I’m still alive to say it’s not true, but it won’t make any difference,” says Kooper. “It’s a quandary.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments