Bob Dylan: How the Isle of Wight festival managed to steal the voice of a generation from Woodstock

Ray Foulk tells his extraordinary story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The day the Woodstock festival opened was an epoch-defining moment in pop. Yet an even more extraordinary event was taking place less than 100 miles away on Friday, 15 August, 1969.

In a journey every bit as unlikely as that of the tin can that had taken men to the Moon less than a month earlier, Bob Dylan and his family were boarding the QE2 in New York to sail to a little island off the south coast of England, snubbing the festival that had been set up in Dylan’s backyard in order to tempt him out of three years’ retirement. In one of the greatest coups, naïve but earnest youngsters were unwittingly stealing the planet’s biggest rock star from the most famous festival in rock history.

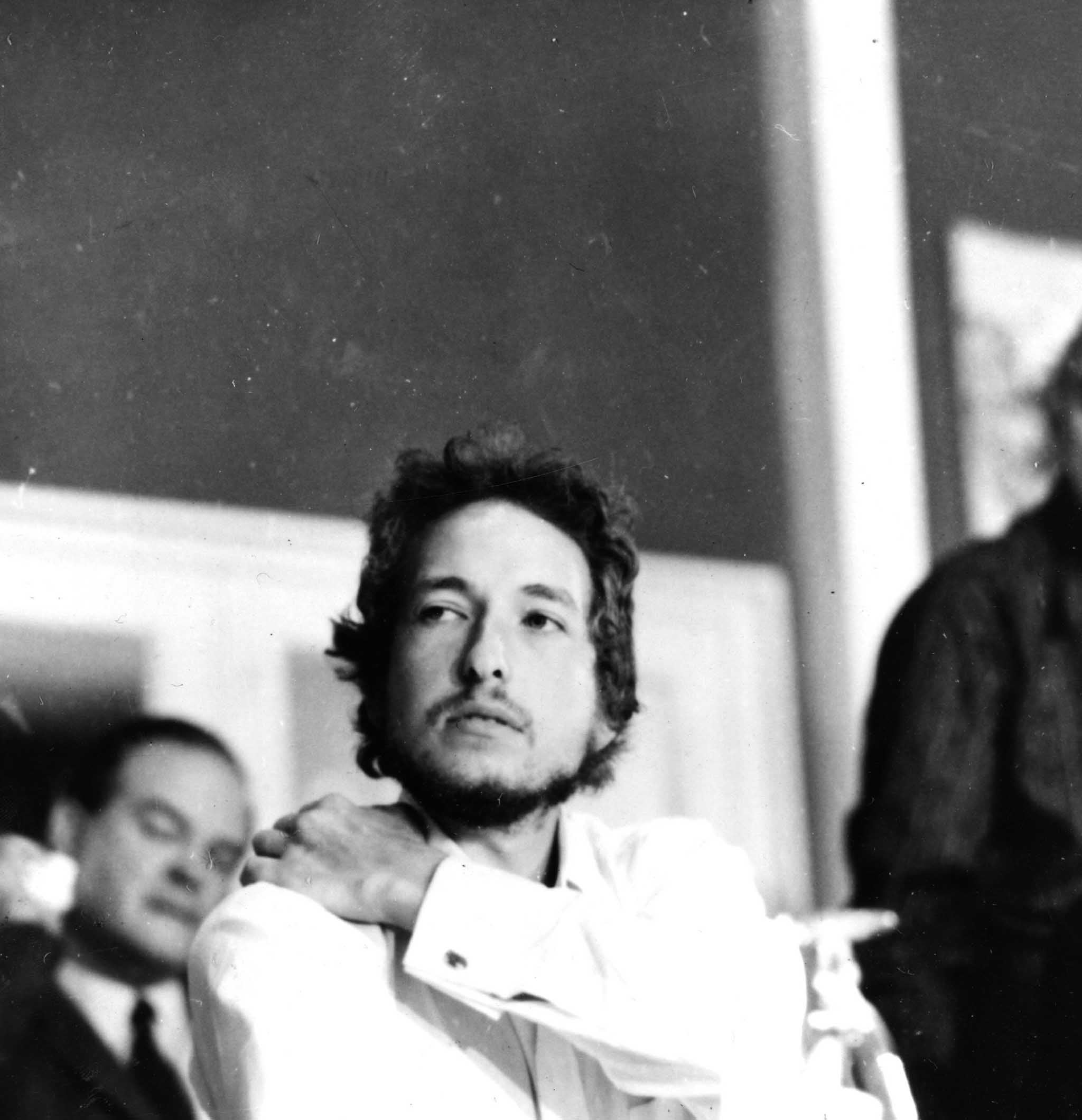

One of those youngsters was Ray Foulk, now a bubbling but unassuming chap with an air of eternal optimism who doesn’t look anything near the 70 years he has spent on the planet. The full story, which he is revealing only now, complete with never-before-seen photographs, sheds new light on a mysterious period in the life of rock’s greatest songwriter, and has a supporting cast of Beatles and other rock gods.

In 1968 Foulk was a 23-year-old newspaper printer, living on the Isle of Wight with his wife and two children. With his brother Ronnie he had organised gigs on the island, culminating that year in an outdoor festival headlined by San Francisco’s hippest hippies, Jefferson Airplane. It drew 10,000 people, but Ray and Ronnie weren’t satisfied. They wanted an act for next year’s festival that would be big enough to pull people across the Solent. So they started thinking ridiculously big.

“We needed a giant,” Ray tells me, “and the giants at the end of 1968 were Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and Bob Dylan. The Stones didn’t have a hippie following then – it was the Hyde Park thing that changed their image.” The Dylan die was cast when, that Christmas, someone gave Ronnie Foulk Dylan’s John Wesley Harding album, and he began playing it to death.

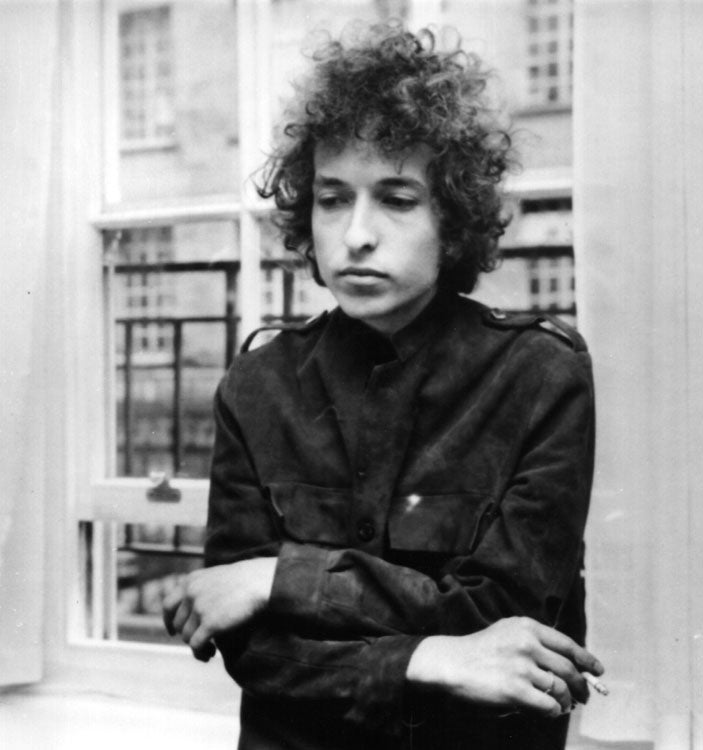

But there was a problem. The whip-thin, Ray-Banned, voice of a generation hadn’t played a proper gig since a mysterious motorcycle accident in 1966. He was living in Woodstock in domestic seclusion with his wife Sara and four children. His own producer had even said that he would never perform again. And, if he was to play, there was, unbeknownst to the Foulks, an enormous big-money festival planned for Dylan’s backyard with the intention of luring him.

“We knew there were big bids for him, but we didn’t know what they were for. We only found out about Woodstock about three days after it had happened,” says Ray.

A trip to London to consult underground magazines revealed Dylan’s management and Ray made contact via a crackly late-night transatlantic telephone call. He was told Dylan might be interested in performing. But they had no chance of competing with big money US promoters. “We started thinking how we could appeal. The Isle of Wight has this great heritage of Tennyson, Keats and Edward Lear that might appeal to a modern-day poet. So we got this idea of selling him a holiday in the Isle of Wight for him and his family.” (They also added a trip from the US to the UK on the QE2, which Dylan liked, though this was nearly to scupper the whole thing).

It worked. When Ray flew to the States to finalise the deal, Dylan came to his hotel room. “He was wearing shades, leather jacket, jeans, boots, generally that kind of hipster character, but he was very quiet and gentlemanly, and most of the conversation with him was about the sound system. He was very interested in that.” They agreed a fee of nearly £40,000 for an hour’s set.

And so, Dylan set sail on the QE2. Except that he didn’t. The Foulks brothers’ dream nearly ended when a cabin door slammed into Dylan’s three-year-old son Jesse’s head, sending him to hospital, and the ship sailed without any of the family. “It was just two weeks before the show, and we got a call. All the papers were saying that Dylan might not appear at the Isle of Wight,” recalls Ray. “Pretty scary stuff.”

Dylan eventually arrived via plane, and no sooner had he and his family and entourage made it to the farmhouse on the Isle of Wight that was to be their base than George and Pattie Harrison arrived with Ringo Starr’s marijuana stash. The two superstars knew each other well – Harrison had stayed at Dylan’s house in Woodstock – but Ray says there was still clearly a mutual reverence.

“I remember [Dylan’s manager] Bert Block whispering in my ear as we were all sitting by the swimming pool and George and Bob were talking and he said, ‘look at them, they’re star-struck with each other!’

“George had the Beatles’ Abbey Road album in his hand, they’d just finished it the day before, and he had an acetate of it. He put it on the record player in the barn and there was a lot of envy in the air… but he was moaning about how John and Paul wouldn’t let him have more than two songs and how unfair it was. I was surprised how openly he was saying all this.”

Another time Ray remembers walking into the living room where George and Bob were singing a close harmony duet of the Everly Brothers’ “All I Have to Do Is Dream” which, he says, “sounded fantastic”.

On the surface Dylan was calm, but occasionally the mask slipped – like when a housekeeper offered him her car to tour the island and he got frustrated trying to peel promotional stickers reading “Help Dylan Sink the Isle of Wight” off the windscreen. “I remember seeing his long nails scratching at these stickers and suddenly he lost his rag, and said, ‘damn these stupid labels!’, and stormed off in a real huff. I realised he was on a very short fuse.”

The gig itself was fraught: 150,000 had massed to hear music’s messiah return, among them, in a chaotic VIP area, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Syd Barrett, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Terence Stamp and Jane Fonda. Dylan was supposed to go on at 9pm, but technical delays meant a two-hour wait as he got more and more agitated backstage.

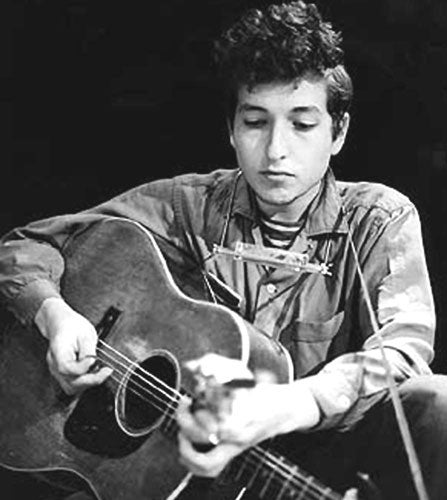

Nevertheless, when he eventually went on stage, he was excited, proudly brandishing his guitar like a schoolboy and beaming: “Look, I’ve got George’s [Harrison’s] guitar!”

He eventually played exactly an hour, just what he had been contracted for, before leaving the stage – portrayed in one of the newspapers as “Dylan walks out in midnight flop”, a review that still rankles with Ray. It’s fair to say that Dylan’s performance was idiosyncratic, and the recording reveals his nervousness, but many there, notably Eric Clapton, were blown away.

For Dylan, though, it may not have been the experience he’d hoped for. He didn’t play another gig for three years and only returned to touring in 1974. Ray, meanwhile, went on to something even bigger – the Isle of Wight 1970 festival (a tale he’ll be telling soon), which would be the biggest the world had ever seen, and featured a man who made his name with a Dylan song and who would be dead three weeks later – Jimi Hendrix.

‘Stealing Dylan from Woodstock’ (Medina, hardback, £22.99) by Ray Foulk (with Caroline Foulk) is released on 4 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments