Arlo Parks: ‘People like to write that I was confused about my sexuality – but I never felt that’

She’s the most hotly tipped British musician of the past year, celebrated for her intimate bedroom jams that blur indie, jazz and pop, as on her debut album this month. Just don’t call her the voice of a generation, she tells Ellie Harrison

It's not every day that one of pop’s top table says that you're their new favourite artist. But that's exactly what happened to Arlo Parks last month when Billie Eilish gave her a shout-out in Vanity Fair. “That was crazy,” says the singer-songwriter, somewhat incredulously. “It’s pretty nuts to think that my little tunes, made in my parents’ house in Hammersmith, have made it across the ocean to one of the biggest and arguably most important figures in pop music.”

Such is the gentle potency of the 20-year-old’s sound, which rewinds to the days of school corridors and stolen glances with the crushing rawness of a forgotten teenage diary found under the bed. Her music draws a line from Nick Drake to Erykah Badu, criss-crossing indie, folk, jazz and R&B without ever committing to either. She sings about sexual identity, queer desire, mental health, body image and the odd ketamine-hazed weekend with an easy poetry that has led her to being called the voice of a generation, over and over.

It’s frosty out near the River Thames as the Londoner pulls in her puffa jacket closer and reflects on being called the pied piper of Britain’s Gen Z for the umpteenth time. She’s flattered by it, though not totally comfortable. “I am of that generation but I'm not speaking for that generation,” she says. “There are so many individuals. We’re not going to all have the same ways of being or priorities or personalities. You can’t have this umbrella thing. Even if you look at other artists my age, people are making completely different music and have different goals. So I don't know how I feel about that, to be honest.”

At the rate she’s going, Parks may well transcend that label soon. She’s in the unique position of having been a hotly tipped artist in 2019, when she released her debut EP Super Sad Generation (you can see from where that Gen Z tag arose), and last year, too. In August, Parks won the 2020 AIM Independent Music Awards’ One to Watch category and in October she was named BBC Introducing’s Artist of the Year. To top it off, she will release her album, Collapsed in Sunbeams, later this month.

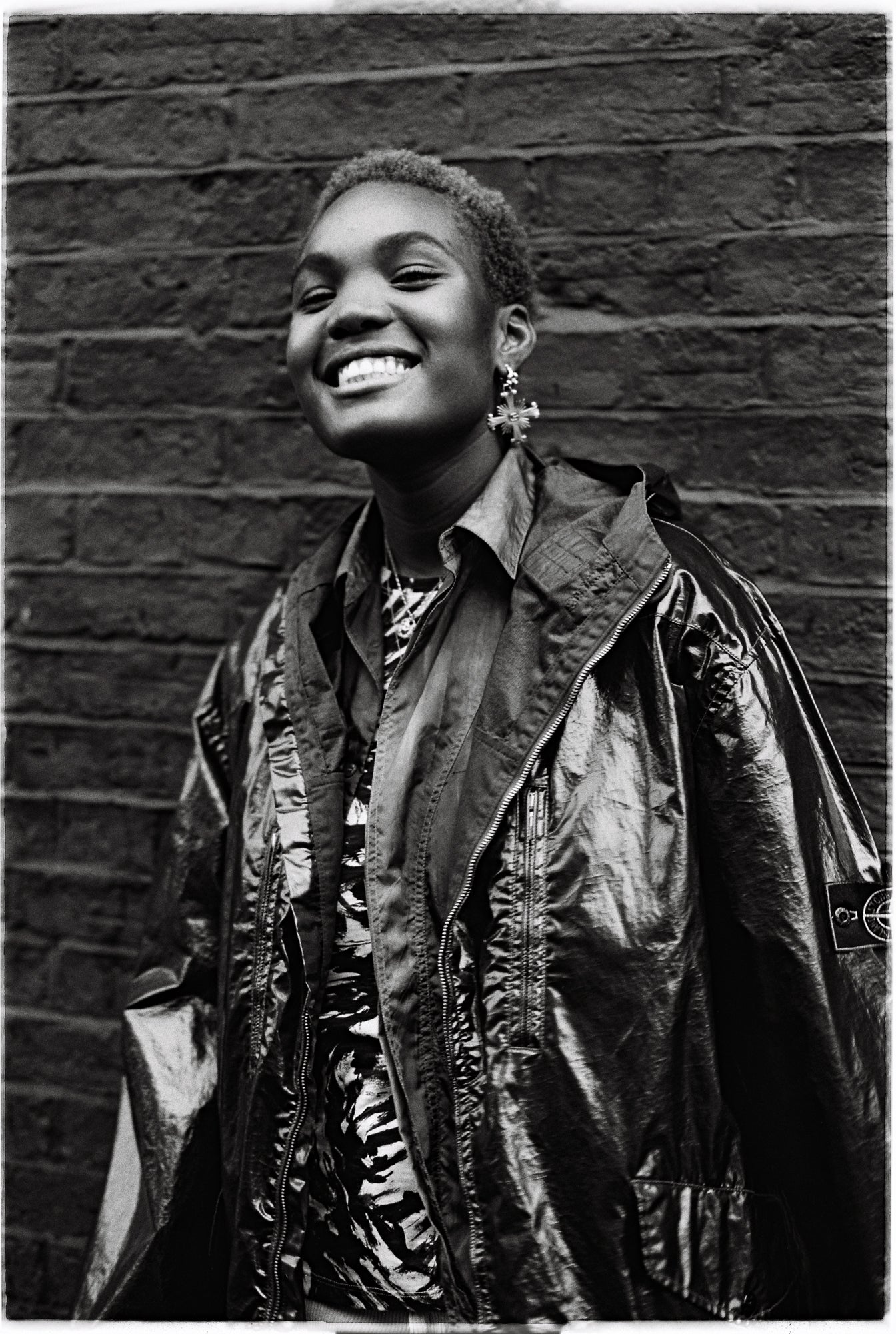

We meet for a wintry December walk along the river, a stone’s throw from her parents’ house in Hammersmith, where she still lives, and not far from where she was educated at private school Latymer Upper. Parks is tall and easy to spot; her hair is close-cropped and dyed the colour of autumn leaves. She has a delicate voice and a tendency to talk about things earnestly, but it’s her genuine sensitivity and perceptiveness that makes her music so poignant. On Collapsed in Sunbeams, she opens with an ethereal poem about self-acceptance: “We’re all learning to trust our bodies, making peace with our own distortions,” she recites.

Parks has been writing since she was a child. “I was in my own world,” she says. “I was writing short stories aged seven or eight. I had a vivid, overactive imagination.” She started out with Bonnie and Clyde-style capers, then plays – “they were not good” – and poetry. “I never stopped writing that,” she says, adding that she plans to release a volume of it one day. “I’ve realised I’m more interested in conveying a mood. I don't really care about the plot.”

Up until the age of 16, Parks says she was reserved and introverted. She had a small circle of friends and studied very hard. She wasn’t bullied, but she also “wasn't part of the popular squad at all”. Her spare time was filled with playing hockey and writing. When she moved schools for sixth-form, however, Parks found kindred spirits. “I was surrounded by people who wanted to be rappers and art directors and curators,” she says. “Having that around me and doing my music made me more extroverted. I had loads of friends and was going to parties all the time, so that was a nice switch.”

Collapsed in Sunbeams is a refreshingly uninhibited record that harks back to those teenage years, hopscotching between optimistic, pop-infused tracks such as “Too Good” and the more plaintive, synthy “For Violet”. It was written mostly in a rented apartment in Hoxton last spring, where Parks could take breaks to cook pasta and play records, which is a little at odds with the knotty themes of the album: addiction, depression, sexuality, unrequited love. But Parks has the canny ability to transport you to another place. “Eugene”, which she wrote when she was still at school, recounts the jealousy she felt as, aged 14, she watched her best friend (for whom she harboured secret feelings) fall in love with someone else. “Seeing you with him burns/ I feel it deep in my throat/ You put your hands in his shirt/ You play him records I showed you,” she sings.

Parks says that she was initially nervous to release something so raw, but ultimately that’s what songwriters have to do. “There is obviously a sense of fear, putting out something where I'm exposing a soft, vulnerable point in myself,” she says. “I was bitter and unhappy with a situation and hurt. But when I realised that it [Parks’s experience] had the capacity to help people, that outweighed the fear. I also think if you don't feel a bit scared when you're putting stuff out, it's not close to the bone enough.”

She has lost touch with the female friend she wrote the song about. “We faded out of each other's lives,” she says. “But I do wonder sometimes what they think of it. They haven't contacted me. They must know.”

Parks says there wasn’t a notable “moment” when she came out as bisexual, it was “always just a thing”. Her parents were very accepting and “never made a massive deal” of it. “They were just like, ‘OK, we love you’,” she says. “And I'm so grateful for that. I learned a lot of empathy and openness from my parents. I know so many people who don't have that experience. I have friends who've been kicked out of their homes over it.”

In the close group of mates Parks had at school, which she still has now, there was “an array of different sexualities and gender identities”, so her relationship with her own sexuality was similarly liberated. “I was lucky the people around me were also figuring themselves out and living their realities and going into relationships with whoever they pleased,” she says. “I never felt uncomfortable. I never felt like it was something I had to explain to them. People like to write that it made me sad and confused and angsty, but I never felt that. Of course, as a teenager, no one is 100 per cent self-assured, but it was just never something that I lay awake at night thinking about.”

Nor did she ever feel held back by the narrow boundaries of music genres. There weren’t many black women playing guitar music as she was growing up but, even so, it didn’t discourage her: she says she has always been more interested in seeing herself reflected emotionally, rather than in terms of her sexuality or race.

“I’ve never thought, because I don't see that many people like me making alternative music, it poses a boundary or I can’t do it,” she says. “It makes me think, oh, OK, well I just need to make something new.” Whether it was King Krule, Syd from The Internet, Beth Gibbons from Portishead or Grant from Massive Attack, there was always this sense of, wow, they’re making something vulnerable or something that feels nostalgic or moving,” she adds.

Parks, who counts Sylvia Plath and Joni Mitchell among her influences, is certainly a moving lyricist. In “Sophie”, which laments the mental health crisis among young people, she sings: “I’m just a kid, I/ suffocate and slip, I/ hate that we’re all sick.” “Hurt”, meanwhile, is about a boy struggling with addiction and in “Black Dog”, which was written for a friend enduring the debilitating day-to-day of depression, she pleads: “Let's go to the corner store and buy some fruit/ I would do anything to get you out your room.”

This friend, Parks is still in touch with. “It really hit her there,” she says of the song, thumping her chest. “The lines are fragments of conversations that we actually had. The first time I played it live she was there in the front row, looking at me, it was so intense. It brought us closer together, to experience that song and the reaction to it. It was something I wrote for her and about us and in homage to this difficult time in our friendship.”

Parks has the rare ability that great poets and novelists have to bottle a feeling with the perfect metaphor and stir in the most specific cultural references, making her listeners feel seen. This is why her work has resonated extremely strongly with fans, and she has even been approached by one person who was considering suicide before hearing her music helped pull them back from the brink.

That’s a lot for a young artist to take on, and she has become passionate about wanting the music industry to provide better mental health support for its stars. “It's a very strange thing to suddenly be approached in the street and have streams of messages, and not know how to work through getting bad reviews and hate comments,” she says. “It's something that can really weigh on the mind and be quite isolating.”

She adds that “especially in confusing times like these, when I feel quite separate from the world, I don’t want to just be living through my phone”. She’s been lucky that, despite the mounting pressure of being a hyped new artist, she’s had “friends and family around me – I feel grounded”, she says. “I can just play Scrabble with my dad and meet my friends in the park.”

But with Collapsed in Sunbeams poised to be one of the breakthroughs of the year, and the end of the pandemic on the horizon, life is about to get a whole lot busier. Scrabble may just have to wait.

Collapsed in Sunbeams is out via Transgressive on 29 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks