The winner takes it all: How Abba’s douze-points energy at Eurovision started a pop revolution

Songwriting genius and satin came together to wow Europe with ‘Waterloo’ on 6 April 1974. As the Swedish stars (and their fans) celebrate the 50th anniversary of Abba’s triumph, Mark Beaumont traces the road to superstardom for Agnetha, Björn, Benny and Anni-Frid

My my – for “Waterloo”, Napoleon was conductor. With one hand tucked into his military blazer, and bicorne hat tugged down over voluminous sideburns, Sven-Olof Walldoff took to the podium at the Brighton Dome on 6 April 1974, struck up his orchestra into a rousing glam swing and was instantly upstaged by two glamorous Swedes bounding down an onstage ramp, wielding silver microphones and radiant in Seventies satin. The dolled-up, dickie-bowed audience, there to politely applaud Europe’s cheesiest musical fripperies, suddenly had front row seats for a pop revolution.

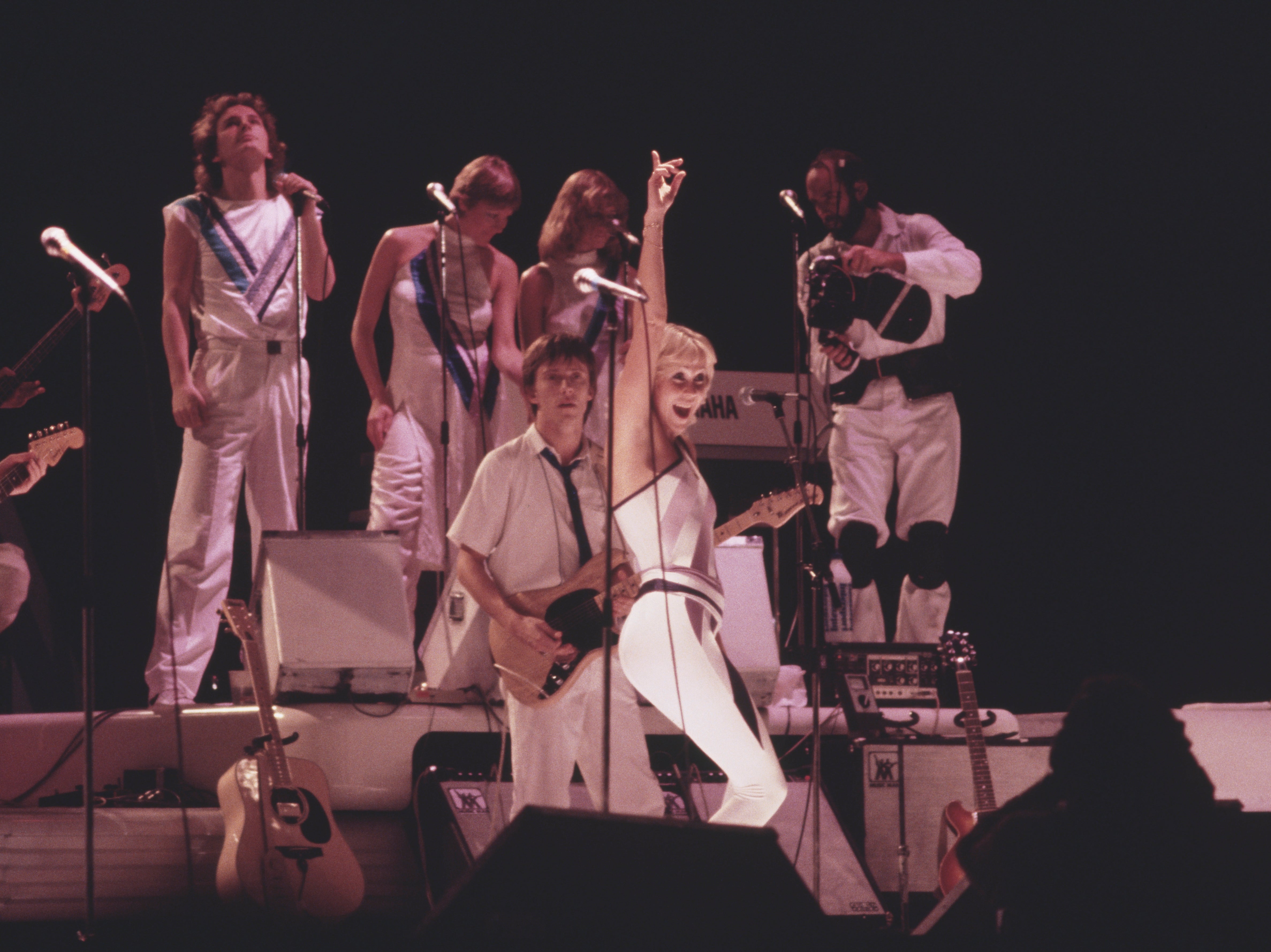

When Abba first burst onto the international stage at the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest, they were clearly brimming with douze-points energy. Centre-stage, Agnetha Fältskog and Anni-Frid Lyngstad beamed their way through this virulently catchy tale of a relationship crushed as if beneath the stampeding hooves of Wellington’s cavalry; Benny Andersson pounded a grand piano in flowing Regency sleeves; while Björn Ulvaeus bobbed cheerily away on a guitar resembling an exploding glitter bomb. Even against such imposing competition as Olivia Newton-John – performing the United Kingdom’s entry, “Long Live Love” – Abba’s “Waterloo” was destined to be all-conquering. What couldn’t be foretold, though, was that it would launch the cavalry charge of a 200-million-selling pop phenomenon, and begin decades of Scandinavian pop music supremacy.

“It starts there with ‘Waterloo’,” says Carl Magnus Palm, Swedish author of the Abba biography Bright Lights, Dark Shadows. “We had talent here, but I don’t think anyone else had the same level of ambition. It’s not like we had pop music on the level that Abba produced before Abba.”

It wasn’t just their outfits that outshone their rivals in 1974 – their pedigree outclassed the average Eurovision hopeful too. The quartet were already stars in Sweden; Andersson had penned major hits with the Hep Stars, known as “the Swedish Beatles”, and by 1969 he’d struck up a fruitful songwriting partnership with Ulvaeus, frontman of popular folk-skiffle combo the Hootenanny Singers. At the 1969 Melodifestivalen competition to choose the year’s Swedish Eurovision entry, Andersson met fellow entrant Lyngstad, a cabaret singer and winner of a Swedish TV talent show. The pair soon became a couple and musical collaborators, Andersson producing Lyngstad’s debut album Frida in 1971. Fältskog, meanwhile, had been producing Connie Francis-style hits in Sweden since her first No 1 aged 18 and would release four solo albums before Abba got into their stride. She met Ulvaeus on a Swedish TV show in 1969; two years later they were married.

“Everything started when Björn and Benny needed female backing vocals, so they brought in their ladies and they did that and it went on from there,” says Palm. “That would probably not have happened unless they’d been in these relationships.”

The four first performed together on a joint holiday to Cyprus, singing for their own enjoyment on the beach and then putting on an improvised show for United Nations soldiers on the island. Gradually their various musical projects and outdoor performances at Sweden’s “folk parks” intertwined until Lyngstad and Fältskog gained equal prominence on Ulvaeus and Andersson’s 1972 single “People Need Love”, a Swedish hit that made minor waves in the US.

Hungry for more international acclaim, and encouraged by their globally ambitious manager Stig Anderson, they once more eyed the Eurovision prize. Having had two entries rejected in 1971, Ulvaeus and Andersson had written Lena Anderson’s third-place song at Melodifestivalen 1972, “Säg det med en sång”, and made the Swedish charts as a result. So they entered again in 1973 as Björn & Benny, Agnetha & Anni-Frid, this time with a song called “Ring Ring”.

The song lost out to a tune that Ulvaeus remembers translating to English as “Your Breasts are Like Nesting Swallows” (actually “The Summer That Never Says No”), but it became a major hit across Scandinavia, as did an accompanying album also called Ring Ring. Yet, despite now being pop celebrities at home, the group still saw Eurovision as their primary route to global superstardom. “We wanted to break outside the borders of Sweden,” Ulvaeus told Billboard. “The only launching pad that really existed for us was Eurovision, because to send songs out was hopeless. No one ever paid any attention.”

“They were successful in Sweden but they weren’t successful in the rest of the world,” says Palm. “In the early Seventies record companies in the UK and the US weren’t terribly interested in music from Sweden. ‘Why would we want to import English-language pop music? We’re doing well in that field already, we don’t need extra talent.’ So, they felt that Eurovision would give them an arena. Björn and Benny say they would never have entered Eurovision otherwise, that was the only reason they did it.”

Even as Ring Ring was circling the European charts, plans were being laid for the invasion of Eurovision 1974. At a piano in Björn’s holiday cottage on the island of Viggsö in the Stockholm archipelago (where many of the band’s major hits would be written), the team concocted an ultra-catchy chorus and handed it to Stig Anderson to work on lyrics. “He thought of lots of different titles,” says Palm. “The only one he remembered later was that he was calling it ‘Honey Pie’ for a while, but that didn’t lead him anywhere, he couldn’t really build a lyrical concept around that, unlike Paul McCartney. But then he had a look in his book of familiar Shakespeare quotations and things like that. And he found Waterloo – it’s a three-syllable word, it’s perfect – and built this story around it.”

“Waterloo” was narrowly chosen as Abba’s entry over another new song, “Hasta Mañana”. “It might sound ludicrous today, but then it was quite a hard decision to make,” Ulvaeus said. “‘Hasta Mañana’ was a solo for Agnetha and a good tune, more in the Eurovision vein than ‘Waterloo’. [‘Waterloo’] was riskier. We took a chance, knowing it was going to be different from all the others. It could have been ‘Hasta Mañana’ and this would never have happened. It would never have won.”

Despite running away with Melodifestivalen ’74, Abba, as they were now known, didn’t arrive at the Eurovision ceremony in Brighton feeling like champions. “We changed into our stage outfits at the hotel, and a bus came to take us to the arena,” Ulvaeus recalled, “I was overweight and couldn’t sit down because my trousers would split.” Even after taking the title in a close-run race – and receiving nul points from the UK in what Ulvaeus believed might have been a “cunning” plot to snatch the prize for Olivia Newton-John – the costumes caused them further grief. “There was some kind of mistake when we won and were going on stage as writers first,” said Ulvaeus. “Stig and Benny managed to get up there, but this guard said to me, ‘No, it’s for the writers.’ ‘But I am one!’ ‘No, no, in that outfit? Writers don’t look like that’.”

“If you think of that performance, they were intent on making an impression,” says Palm. “You dress up in crazy costumes, you have Napoleon as conductor, everything you could ever think of to make a splash, to make them noticed. They weren’t leaving anything to chance.”

“I hardly remember anything other than waking up the next day and finding myself and us being all over the globe suddenly,” Ulvaeus told the BBC. “[We had] gone overnight from this obscure Swedish band to world fame... So unreal.” “The world was opened to us,” he said in Billboard. “One night, and it all opens up.”

“Waterloo” was a Europe-wide smash, and even made Number 6 in America, but Abba’s long-term success was anything but overnight. Glam style follow-up singles flopped, and it would be 18 months before they had another major international hit. “It was a very difficult period,” Ulvaeus said. “Everyone had decided we were a one-hit wonder because we came from Eurovision. And, with very few exceptions, they are one-hit wonders. So that helped, especially in the UK, to hold us back.”

“It manifested itself quite literally,” Palm says. “Every trip they made there for promotional trips they got a gradually less classy hotel and gradually less classy car. Once they came back with ‘SOS’, though, the subtext [in the British music press] seemed to be ‘I’m not really supposed to like this but this is actually good quality pop’. Some of the UK music journalists even compared them with other UK acts of that ilk and said this group of Swedes are wiping the floor with them.”

And how. “SOS” set off an eight-year torrent of pop gold unrivalled in its era: “Mamma Mia”, “Fernando”, “Dancing Queen”, “Money, Money, Money”, “Knowing Me, Knowing You” and “The Name of the Game” stormed global charts in the following two years alone, making Abba one of the biggest pop phenomena of all time. So popular were they in the UK that the 3.5 million postal applications for tickets to their two 1977 shows at the Royal Albert Hall could have filled the venue 580 times over. Amid the rush, Andersson and Lyngstad also married in 1978, and Palm believes that the relationships between the two couples were only strengthened by the success of the band.

“If you ask them they will tell you that the relationships weren’t really affected so much by Abba and whatever pressure Abba were under,” he says. “On the contrary, they say that if it hadn’t been for Abba, those marriages would have ended much sooner, because Abba gave them a centre. Everything they did was centred around Abba. It gave them a sense of purpose and it seemed to be like, ‘Where do our relationships start and where does Abba end?’ It was intertwined.”

Nonetheless, by 1981 – in the wake of further hits in “Chiquitita”, “Voulez-Vous”, “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” and “Super Trouper” – both couples were divorced. “They haven’t talked too much about it but Björn and Agnetha just grew apart,” says Palm. “I know they felt they married too early, I know Agnetha did, she was only 21 when they married, and they kind of realised ‘maybe we are too different as people’… they were failing to communicate. They went into couples therapy but the therapist told them, ‘Actually, you’ve probably reached the right conclusion – you shouldn’t be married any more. You’re not compatible anymore.’ For Benny and Frida, I think it was pretty much the same thing. There was also quite a lot of drama and ups and downs in that marriage.”

It’s been speculated that marital issues contributed to the bitterness in songs such as “The Winner Takes It All”, but the band disagree. “There’s a small percentage there that may have to do with his breakup from Agnetha, but it’s not a literal depiction of what happened to them,” says Palm. “It wasn’t a matter of winners or losers. They were both losers, if anything.”

Abba continued post-splits, but touring had been a problem since Fältskog’s fear of flying had been exacerbated by a terrifying experience between New York and Boston in 1979, when the band’s private jet hit a tornado, ran short on fuel and had to make an emergency landing in New Hampshire. “The pilot failed to land at the first attempt but then we landed at the second try,” she told The Sun. “It stopped me flying. I try not to think of it as it was terrifying. I already had a fear, but this event was the turning point. I had to have therapy for my fear – it’s getting better but it takes a long time.” For years to come, Fältskog would only travel by bus, which proved no safer; in 1983 she was thrown through the window when her private bus overturned in southern Sweden. She’s lucky to have survived.

Although they never officially broke up, as their star began to decline Abba bowed out with the rousing “Thank You for the Music” in 1983. “We might have continued for a while longer if [‘The Day Before You Came’] had been a number one,” Ulvaeus said. Ulvaeus and Andersson threw themselves into an equally high-vaulting career in musicals, with Chess and Mamma Mia! among their biggest successes. Fältskog embarked on a mid-Eighties solo career, having major hit albums in Scandinavia, but took a 17-year hiatus from music from 1988 to concentrate on yoga and astrology; Lyngstad also successfully went solo, while taking on the title of Her Serene Highness Princess Reuss when she married Prince Heinrich Ruzzo of Reuss, Count of Plauen, in 1992.

For many years – despite huge public demand and even as relations improved between the Abba members, with joint public appearances made at Mamma Mia! musical and movie premieres around the world – all attempts to get the band to reform were rebuffed. “We will never appear on stage again,” Ulvaeus told the Telegraph. “There is simply no motivation to re-group. Money is not a factor and we would like people to remember us as we were. Young, exuberant, full of energy and ambition.”

“I don’t think there was any animosity, because after a few years when everyone had put some distance between the divorces and the whole Abba experience, they were all good friends again,” says Palm. “If anything, things have only improved over the years. It’s just that Björn and Benny in particular, they’ve always been, ‘We don’t want to go back, reuniting Abba is going back, we want to move forwards… there’s no point in trying to reheat the soufflé, it’s impossible to do.’ No-one’s been really interested in being Abba, and going on tour is out of the question. They had this billion-dollar offer for a reunion and they said no to that. It’s not like they need the money. They’re all wealthy anyway. It was like, ‘I’m gonna age 10 years if I do 100 concerts – it’s too much’.”

Then in 2018, just as the movie sequel Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again heightened interest in the band once more, news arrived that the band had recorded two new songs, “I Still Have Faith in You” and “Don’t Shut Me Down”; their ninth, final album Voyage was released in 2021. Their London residency of the same name, at a purpose-built studio in Stratford, launched the following year with their hologram “Abbatars”.

“I would say that part of the attraction for them is that they don’t have to go out and promote it, because the avatars will do it for them,” Palm says.

They have, after all, done quite enough for one pop lifetime. Besides writing one of the finest canons of pure pop music of the post-Beatles era, Abba lay the groundwork for Scandinavia to become hailed as home of the glittering chorus (acts like The Cardigans, Ace of Base and today’s premier Scandi super-producers all trod in their stack-heeled footsteps) and, however briefly, gave 1970s Eurovision the credibility of a hotbed of genuine world-beating talent. They were a page of pop’s history book, in short, which would rarely repeat itself.

This article was originally published in 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments