David Bowie: How streaming online music has changed the music industry's control after a music legend dies

When a superstar like David Bowie dies, labels traditionally rush to re-release their hit records. Now, for the first time, online music has put the fans in charge

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1980, John Lennon released an album, entitled Double Fantasy, with his wife, Yoko Ono. It was the former Beatle’s first foray into music for almost five years, but it didn’t exactly set the world alight.

Three weeks later, Lennon was gunned down in New York by Mark Chapman and the world, mourning the tragic passing of a pop icon, elected to show its collective grief by investing in his most recent work. Suddenly, Double Fantasy was a No 1 all over the world.

“That wasn’t his record label’s doing, that was the public’s,” says David Hepworth, the veteran music writer and founder of Smash Hits, Q and Mojo magazines. “When a rock star dies, huge amounts of people decide to express their feelings by buying their records. They just do, always have, always will.”

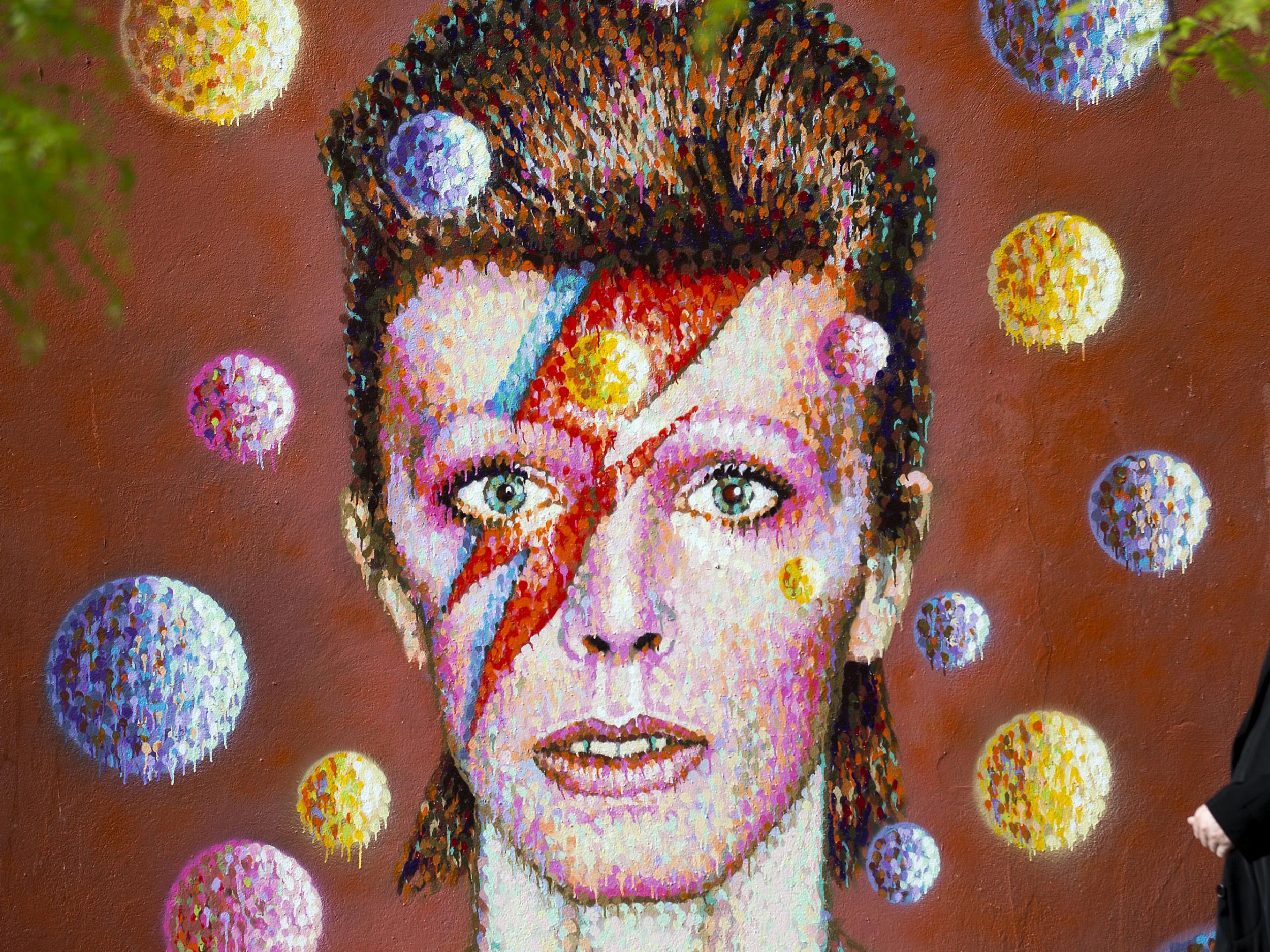

In the days since Bowie’s death was announced on Monday, his music has been inescapable everywhere: usurping radio playlists, all over the BBC, and piping from department stores that would otherwise be playing today’s hits, and only today’s hits.

In one sense, this is not surprising: nothing quite whets the appetite of music lovers – and starts to resemble a cash cow for record labels – like the untimely death of a singer.

But Bowie was no ordinary rock star. Rather, he was an artist so avant garde and daring that he stage-managed his career right to the very end.

Three days before he died, he released Blackstar, a valedictory album that few realised was quite so significant – at least for 72 hours. His second album in three years, after retreating from the public eye in 2004, it was one of the best-reviewed records of his career.

Blackstar is a dense work, and, until his passing, was an oblique one soaked in free jazz and seemingly un-interpretable lyrics. The title track, with its talk of executions and death (“something happened on the day he died,” he sings) was about so-called Islamic State, according to the album’s saxophonist Donny McCaslin; it is now more widely read as the singer saying goodbye to a creative world he helped mould.

While it perhaps wouldn’t have converted any of those for whom Bowie remained an acquired taste, it was still anything but a going-through-the-motions effort from a fading rock star. It was always going to sell.

“And that isn’t something we should overlook,” says Martin Talbot, of the Official Charts Company. “Over 50 years since his first record, he remained incredibly relevant to his audience. The sales figures for Blackstar last weekend alone had it way ahead of anyone else in the charts. It was comfortably going to be No 1 before we all woke up to the terrible news on Monday.”

If Blackstar was already destined to be a big record, then, it is now merely the ripple that precedes the flood. At the time of writing, Bowie has six albums in the Top 40. On America’s iTunes chart, meanwhile, no fewer than 28 of his albums have re-entered the Top 100 – among them 1972’s Ziggy Stardust, 1977’s Low and 1983’s Let’s Dance – along with 21 singles.

His back catalogue is streaming at full pelt across Spotify, where, on the day his death was announced, 30 times as many people listened to Bowie tracks, and five of the top ten tracks streamed in the UK were by Bowie. For the next few weeks, all music is David Bowie’s music.

“When a music icon dies, we usually see an outpouring of grief and loyalty towards the artist that can find expression in increased demand for their work,” says Gennaro Castaldo, of the British Phonographic Industry, and who used to work for retailer HMV.

“Partly, it is to feel an emotional connection when we suddenly realise they are no longer with us, but also because the accompanying media coverage may prompt a desire [for people] to reacquaint themselves with certain recordings. In the face of such demand, some titles may be reissued accordingly.”

Though Parlophone/Warner Bros, which owns the bulk of Bowie’s back catalogue, hadn’t said at time of writing whether it would start re-issuing his work, record companies have long been aware of the profitability of this. How better to reinvigorate interest in otherwise forgotten songs?

Some outlets are keen to distance themselves from such an accusation – the independent record shop Rough Trade, for instance, is donating all profits from sales of Bowie titles this month to Cancer Research UK.

“People have very mixed-up feelings about their favourite rock star’s death,” David Hepworth suggests. “They like to think that their affection is pure and that they are not being cynically manipulated. But they aren’t. I don’t think a record company’s response to an event like this is any more cynical than, say, a newspaper’s, or the BBC’s. They are simply reflecting what people are interested in.”

Before streaming gave the public more freedom over what in their favourite artists’ back catalogues to revisit, labels did reissue albums, and tended to cherry-pick the most likely lucrative titles. Curios and experimental records were invariably overlooked in favour of safe bets like anthologies and greatest-hits compilations. But this will not be the case with David Bowie, and not simply because he was David Bowie.

Paul Gambaccini, the Radio 2 presenter and long-term Bowie fan, says: “What is so important here, and what is completely different from every previous pop star’s death, is that previously people had to buy physical copies of albums, and were focused on the products the record companies were promoting.

For example, when Michael Jackson died, there was a focus on his Number Ones album, The Essential Michael Jackson and Thriller. But now that people stream albums, record companies are powerless. For the first time ever, it really is consumer-driven and from the heart; it is the public that is in control.”

This seems an fitting legacy for an artist who never considered himself part of the regular music industry.

But Martin Talbot argues that record companies with their eyes on so obviously crass a prize are a thing of the past anyway: “What often gets overlooked here is that record companies have an emotional attachment to the artist they work with, and so the response to a death is a very human one. To be seen as insensitively cashing in would send out a terrible message, and on social media the backlash would be horrendous.”

But it does still happen. On a compilation of demos and outtakes released last year entitled Montage of Heck, former Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain can be heard blowing raspberries. Let us pray we never get to hear David Bowie doing anything similar.

“I suppose it is inevitable that somebody somewhere with a copyright to something of his will release more Bowie music in the future,” says Gambaccini, “but then that’s capitalism, and it has nothing to do with Bowie’s artistic plan. Blackstar was a masterstroke on his part to make even his death the work of performance art. And so perhaps in this case there will be no postscript, no more music from him. This might well be the end. And what an end.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments