Blue Note Records, 'jazz's Motown', on celebrating 75 years in the limelight

Blue Note remains more than the shell of a name that other formerly legendary labels – Virgin, Island, Motown and EMI – have been reduced to according to Nick Hasted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The jazz label has changed since its inception 75 years ago. But it hasn’t lost touch with its roots.

Blue Note, one of the greatest indie labels ever, was founded 75 years ago. What Motown was to soul, Blue Note was to jazz: synonymous with a sound it not only released, but defined. Its anniversary celebrations are therefore stretching through 2014, with November alone seeing the release of a lavishly illustrated book, Uncompromising Expression, a singles box-set and commemorative gigs. One-hundred key albums are also being reissued on vinyl and download.

But Blue Note now is not Blue Note then. The label founded in New York in 1939 by the Berlin émigré Alfred Lion out of a pure love for jazz ceased to be independent when he sold it in 1966, and closed in 1979. Revived by EMI in 1984, a corporate merger shunted it into the Universal Music Group in 2012. Its current roster includes Elvis Costello, Van Morrison, Norah Jones and Roseanne Cash, whose jazz credentials range from some to none.

But, somehow, Blue Note remains more than the shell of a name that other formerly legendary labels – Virgin, Island, Motown and even EMI – have been reduced to. The Blue Note blowing out its birthday candles this year doesn’t feel like a fake.

Don Was, the former Was (Not Was) musician and Blue Note boss since 2011, believes its corporate present still connects to its past. “Alfred Lion and his partners wrote a manifesto in 1939,” he says. “They dedicated themselves to providing an avenue for artists to express themselves in uncompromised fashion. Alfred also had a sense that when you’re doing improvised music, you’re supposed to do it differently every time, and he mirrored that in the label.

“So for me, Van Morrison steppin’ up to the microphone and delivering a song is not that different to [saxophonist] Wayne Shorter doing it. They may use different modes, but I don’t think the label should discriminate on that level. I’m looking for an emotional impact, a unique point of view, and good groove. And that’s kind of it.”

%20and%20Francis%20Wolff.jpg)

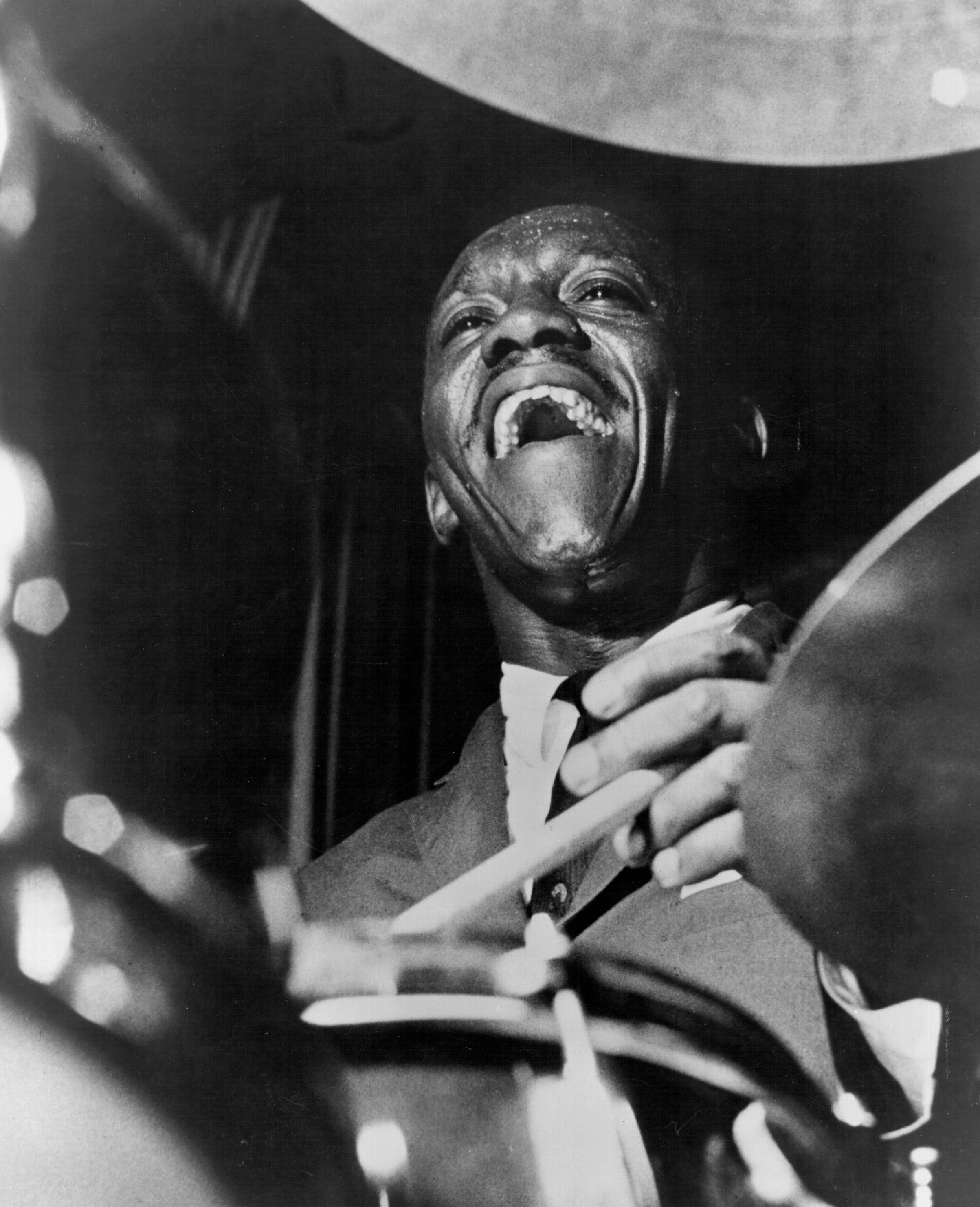

The Lion “manifesto” Was refers to was more specific, committing Blue Note to “the uncompromised expression of hot jazz and swing”. Jazz styles changed, but the label gained its own, unmistakable look and sound. Lion produced sessions with a fan’s passionate instinct. His friend and fellow Berlin Jew Francis Wolff, who took “the last boat” from Nazi Germany to New York in September 1939, added his business sense and took evocative photographs in the studio.

Starting in 1956, Reid Miles wove strikingly stark, modern LP designs around these photos of working musicians. A current Blue Note artist, the intense and lyrical young trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, has recalled the importance of such pictures in his desire to play jazz. “When I look at those old photos of black guys in the 1950s and 1960s and the social problems they had to live through, and the pride and resilience on their faces,” he told Jazzwise magazine, “why wouldn’t I want to be connected to that?”

Equally crucial was the engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s precise and atmospheric recording of the music, initially in a studio in his parents’ New Jersey front room. “A Van Gelder piano chord is even more instantly identifiable than the style of the pianist who’s playing it,” Richard Cook wrote in Blue Note Records: The Biography.

This quartet’s tireless work was the recognisable frame around the “hard bop” style musicians such as the drummer Art Blakey and the pianist Horace Silver developed over dozens of Blue Note dates, returning elements of gospel and blues to jazz, and dominating it in the 1950s and early 1960s. A recent LP reissue, Silver’s Song for My Father, lets you admire Wolff’s warm cover photo of Silver’s dad as you listen to the music’s soulful, surprising ideas, and drop in to Blue Note’s complete, capacious world.

Alfred Lion retired in 1967, and Francis Wolff died in 1971. Without them Blue Note expired, out of touch and unmourned. But its peak years left behind a depth of affection which was, it turned out, only dormant. When the music business veteran Bruce Lundvall resurrected the label for EMI, his own love for its legacy helped shield it from harm.

His new signings included Norah Jones, whose 2002 debut album, Come Away with Me, sold 26 million copies. Jones wasn’t jazz, but she demanded to be on Blue Note. Her success has subsidised it ever since. “The patron saint of jazz for the last 10 years has been Norah Jones,” Was laughs. “Norah enabled a lot of cool music to be made. She’s the Medici of Blue Note jazz.”

Blue Note is no longer independent, nor solely a jazz label. It has survived by diluting what made it distinct. But the label still tends roots that Lion would recognise. The Robert Glasper Experiment’s album Black Radio (2012) was a Grammy-winning US bestseller, adding hip- hop and nu-soul singers such as Erykah Badu to the jazz keyboardist Glasper’s sound.

The powerhouse soul-jazz singer Gregory Porter, meanwhile, signed to Universal just before it acquired Blue Note, arriving by a corporate accident at his natural home.

“Robert Glasper is very much in the tradition of Blue Note jazz heroes,” Was believes. “If you go back to Herbie [Hancock] and Wayne [Shorter] in the 1960s, those guys were reflecting the times they lived in, and Robert does the same thing. He plays his life. So if he’s playing Thelonious Monk’s “Well, You Needn’t”, in his jazz stream of consciousness a J. Dilla rap record is going to make its way in, as it should. And Gregory’s sold 500,000 of his album, Liquid Spirit. He has transcended, at least financially, the parameters of jazz.

“Through all the different management regimes, people dug having Blue Note there,” Was concludes, considering the corporate survival of Lion’s proud little label.

“All Lucian Grainge, of Universal Music, has really said to me is, ‘Keep making tasteful records.’ That’s my directive, from the head. I haven’t had a problem.”

The next Blue Note reissues are out on LP and download on 25 August. ‘Uncompromising Expression’ is published by Thames and Hudson on 3 November. Blue Note release a box-set of that name the same day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments