Would my tragic, schoolboy love be requited on the golden fells of the Lake District?

In his series recalling memorable walks and pathways, Will Gore remembers how dreams of teenage romance came to naught in the Cumbria hills

There is perhaps nothing quite as exquisitely painful – emotionally speaking – as unrequited teenage love. It feels like it at the time anyway.

In my last year of secondary school, I and three friends (one of whom I was completely and utterly in love with) managed to blag a grant to undertake a “geography project” in the Lake District. The basic premise was that we would spend five days in Cumbria documenting evidence of glaciation.

Two 16-year-old girls and two 16-year-old boys heading off on a post-exam holiday sounds like a recipe for drunkenness and sex. In fact, it was nothing of the sort. While the geographical studiousness of the trip was limited, the whole thing was more Swallows and Amazons than Mills & Boon.

I was a shy teenager, especially when it came to girls. I certainly hadn’t revealed to my friend that I was crazy about her – although who knows what might have been guessed. I didn’t really even know how to go about telling her. The chances of anything happening between us were therefore limited: but my innocent belief in the power of love meant that I lived in desperate hope.

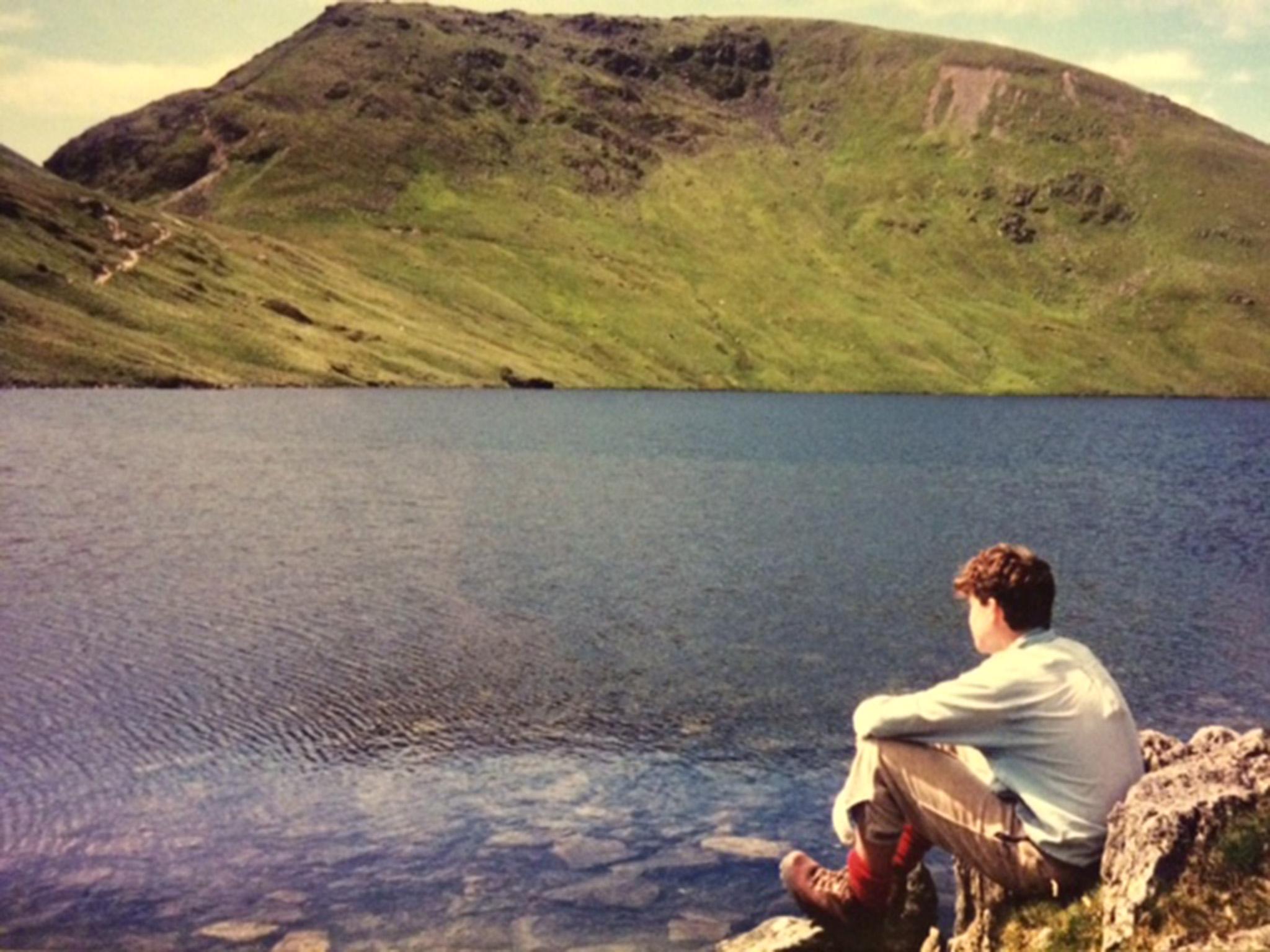

When we headed to the Lakes I had visions of romance blossoming on sunny uplands or by sparkling waters – notwithstanding the presence of our other companions. Perhaps she might stumble and I would heroically save her; and she would look into my eyes and realise I was the guy for her, like something out of Pride and Prejudice.

After the summer, she and I went to different sixth form colleges. We saw each other on the bus sometimes, and occasionally in Cambridge pubs, but gradually lost touch. I should have been braver of course; should have told her how I felt

Our plan was to walk between youth hostels, doing enough “work” along the way to satisfy the requirements of the grant. Atypically for the Lakes, the weather was perfect and we set off on our second day in good spirits, leaving Ambleside with the sun already warming the Eastern Fells.

With Patterdale, our destination, about 11 miles away – and with an ascent and descent of Fairfield in between – it was always going to be our most strenuous hike of the trip. By the middle of the morning, the heat was intense and our pace had slowed. The chances of love blossoming seemed ever more remote as the mood between the four of us became moderately fractious.

I tried to jolly everyone along, desperate to avoid arguments that might sour the rest of the expedition. I was the kind of schoolboy who used humour to hide both my shyness and fear of confrontation; but as temperatures soared, my jokes received a cool response.

The relief of arriving at the hostel in Patterdale quickly restored good tempers, however – and not a moment too soon. We agreed that the long circular walk we had planned for the next day might reasonably be curtailed in favour of lounging around on the shore of Ullswater.

Over the remainder of the holiday I waited patiently for the moment that cupid’s arrow would somehow, miraculously, strike. But the object of my affection never stumbled; I never saved her heroically; she never looked deeply into my eyes and returned my loving gaze.

After the summer, she and I went to different sixth-form colleges. We saw each other on the bus sometimes, and occasionally in Cambridge pubs, but gradually lost touch. I should have been braver of course; should have told her how I felt.

But then, love is a difficult terrain – and sometimes the path not followed is best left that way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks