It’s important to listen to imaginary voices – just ask Virginia Woolf

The voices you hear may be a driving power of your creativity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Centuries ago, hearing voices in one’s head was thought to be a sign of communication with God – and if not that, then with the devil. In more recent years, it is associated with madness. But the concept of imaginary voices is also one that is profoundly literary. Fiction can be “experimental” in the scientific, as well as artistic, sense: a vehicle for investigating the role of voice in ordinary thinking as well as in creativity. Authors, too, can experience inner voices as “auditory verbal hallucinations”.

I was recently involved in curating the world’s first exhibition of voice hearing, currently showing at Durham University. Hearing Voices: suffering, inspiration, and the everyday explores how hearing voices that have no source is a common feature of our lives as well as an aspect of visionary experience, creative or psychotic states. This might include a bereaved person comforted by the voice of the departed; a mountain climber who intuits a felt presence; a child talking to imaginary friends; an athlete whose attentional focus tunes in to self-talk; the inner voice of a coach or trainer.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

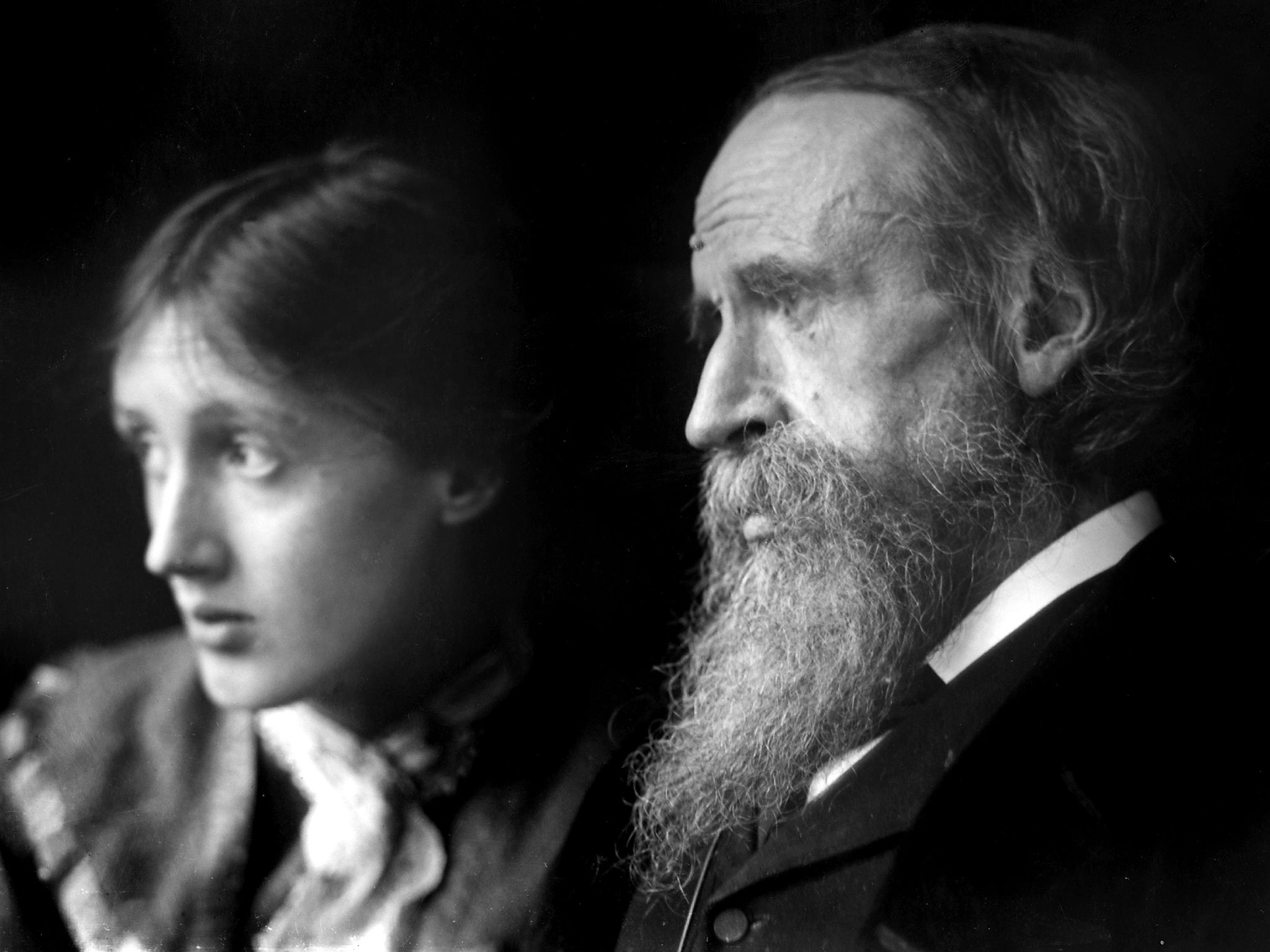

The most famous literary voice hearer was Virginia Woolf. Photographed by Man Ray for Vogue’s roll call of influential people in 1924, appearing on the cover of Time in 1937, and subjected to further iconisation in the Burton/Taylor film of Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf in 1966, Woolf remains perennially fascinating as a compelling amalgam of female aristocratic beauty, doomed talent, Bohemian and suicide.

But surely no one’s really afraid of this safely contained popular image of creative “madness”? Woolf’s private agonies of soul lay behind the glamorous iconic image: between the ages of 13 (when her mother died), and 33 (when her first novel was published), she suffered a series of major psychotic breakdowns, involving, most famously, birds singing in ancient Greek. But she learned to manage the public image, accepting the hereditary-genius stereotype as the daughter of the irascible and often brilliant Leslie Stephen and using the infamous rest cure for “neurasthenia” as an opportunity to withdraw into creative mind-wandering.

She also learned to manage the voices and had no further complete breakdown until the end of her life. Populists, feminists, literary critics, gay activists, have since claimed her as their own. But her archive can be seen as a serious resource for research into the experience of hearing voices. In a 1919 essay, Woolf exhorted her reader to scientifically “examine an ordinary mind on an ordinary day”. She saw no contradiction in describing the mind as a visionary “luminous halo” in the very next sentence. Her voices were at once mystical experiences and objects of her own scientific investigation.

Research shows how abuse in early life often mediates distressing voice-hearing experiences in later years. Woolf intuited the connection for herself from 1920 when she first spoke out, to the Memoir Club, of the incestuous sexual abuse suffered as a child. She saw plainly the connection between the terrible events of her early life – traumatic deaths, sexual abuse, patriarchal coercion and familial neglect – and the voices of the dead that spoke to her, especially her mother’s (she simply “rages” against her father), as well as the more bizarre birds singing in Greek. She saw too how developing “shock-receiving” abilities allowed her to become a writer and how that protected her from psychotic breakdown.

Channelling voices

In letters, diaries and memoirs, she discusses how entering the “queer” place of composition allowed her to step into memories that felt more real than the present; how this required shifting her mental state voluntarily into one of controlled dissociation. This is the same splitting of consciousness that involves splitting off some mental processes so self-awareness operates in two or more spheres each closed off from the other. This consciousness “dissociation” manifests in extreme form in multiple personality disorders.

Her fiction, directly or indirectly, explores this shift in mental states. In On Being Ill, Woolf describes the uncanny slipping away in illness of the structures of the familiar world, of time, space, secure embodiment and emotional centredness. This is what psychiatrist Karl Jaspers (1913) had described as the prodromal phase of psychosis: a phase unavailable, he claimed, for understanding or anchoring to the present.

Woolf thinks not. In To the Lighthouse, Woolf’s most autobiographical novel, Lily Briscoe enters her own “queer zone” after the death of her friend and host Mrs Ramsay. Although poised to leap riskily into the “waters of annihilation” as she embarks upon her painting, she summons all her will as she takes up her brush, calling up past scenes in her mind while holding a “vice-like” grip on the perceptual present.

As the painting emerges, the “residue” of her years now achieving formal and emotional balance, she sees how, through the project of creative reshaping of memory of the past, one might no longer be condemned to a solitary sense of shame. Woolf laid to rest the voice of her mother in writing the novel. She seems to have stumbled too upon the basic processes of contemporary trauma therapy.

Woolf’s imaginary voices spurred her on to invent ever new possibilities of fictional voice. In Mrs Dalloway, she invents a manner of writing that is the modern equivalent of the Greek chorus, reinventing the crowd as a multitude inside and outside the head. Ethical insights follow: in creativity and distress, she recognised we are many and not one.

Woolf, the feminist, knew that our liberal plural ideal of persons must acknowledge the vast diversity of the human race. But if we flee from the idea of the diversity within, by calling it madness, how are we ever to celebrate the differences we encounter in the world outside ourselves? Novels allow us to listen in and to learn political, ethical as well as cognitive lessons about what goes on as our mind continues the endless dialogue with itself that is living.

, Professor in English Literature, Durham University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments