Is there a future for the traditional museum?

There are now 55,000 museums worldwide – double the number in 1990 – with a new one opening every day in China alone. But as they begin to morph into big-business brands, and we become ever more digitally obsessed, can this trend continue?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's a Sunday afternoon in October at the British Museum. Everyone comes to museums to look at the stuff on display, but looking at the people doing the looking is often as interesting. There are excited kids and bored teenagers, nonplussed parents and not-fussed couples. There are also huge groups of Chinese tourists crocodiling from Norman Foster's covered courtyard into the museum's new extension – a sober £135m box by Graham Stirk – to see the current blockbuster exhibition filled with Ming vases whose plinths should definitely not be leant upon, Groucho Marx-style.

Our museums seem to be booming. Visitor numbers rise and rise. It's open season for new openings, and for the big-name architects who nowadays spend most of their lives knocking up anodyne towers for overseas tycoons, building a museum extension must seem like a rare laugh.

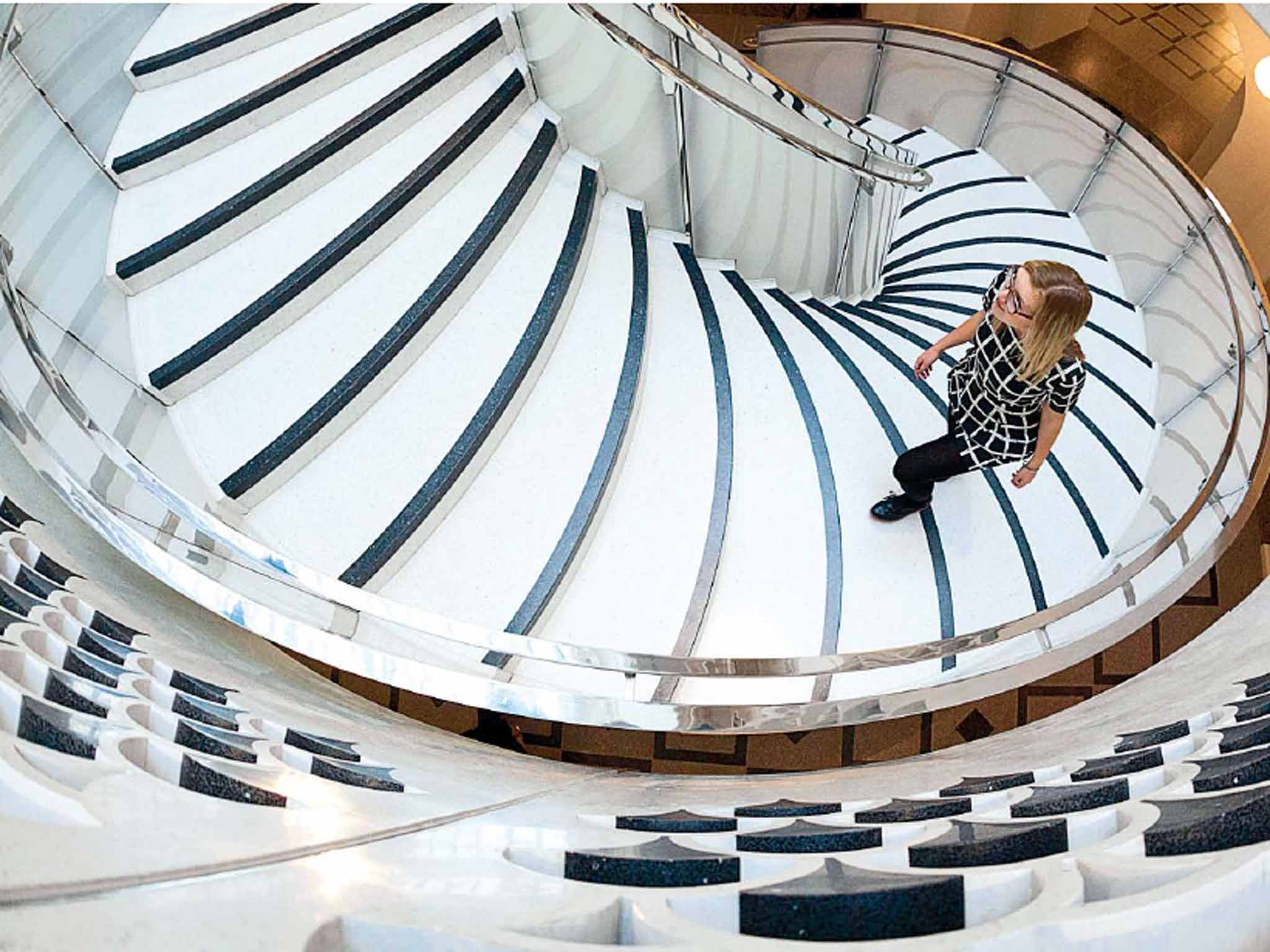

The Queen cut the ribbon on the Science Museum's new permanent Information Age gallery last month. Tate Britain splashed out £45m on a refurbishment by Caruso St John – with a pleasing spiral staircase at its heart – which opened earlier this year. So did the Imperial War Museum's £40m upgrade by Fosters. It's barely two years since Belfast's Titanic Museum, three since Zaha Hadid's Riverside Museum in Glasgow, and four since Zaha won the Stirling Prize for MAXXI in Rome.

Tate Modern is erecting a new building next to Bankside Power Station by Herzog & de Meuron, the Design Museum will be moving into RMJM's derelict Mad Men-esque Commonwealth Institute in Kensington in 2016, and the Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch is expanding. The Aga Khan Museum has just opened in Toronto, New York has its new 9/11 Museum, Stanford and Harvard Universities have invested in new museums, the Richard II Museum is new to Leicester, Coop Himmelb(l)au's much-delayed Musée des Confluences opens in Lyon next month, just like Barcelona's new design museum. The Economist reckons we now have 55,000 museums worldwide – a number that has, incredibly, doubled since the 1990s. China averages a new museum every day. >

Curiously, we don't splash out on council houses or universities or hospitals any more – but we do build museums and galleries. They're a reliquary for our collective memories. And they're a triumph of our collective will. "Museums have reinvented themselves," reckons Sharon Heal, editor of Museums Journal. "They've been improving for decades, but I think it's only in the past few years that public perceptions have really changed."

For Alain Seban, president of the Pompidou in Paris: "Museums are places where things are considered in the long term. They serve as beacons, distilling a sense of authenticity and truth – and they are also, quite simply, places of beauty and meditation. In an era of doubt, of uncertainty, of rapid change – the audience's enthusiasm is hardly surprising." High ambition requires leg work. Museums need visitors and they need money, as Science Museum director Ian Blatchford cautions: "London's major museums have benefited from recent growth in international tourism, though the picture elsewhere [in Britain] has been patchy. Ambitious programming and creative marketing have been key to record visitor numbers. This requires investment – so I'm afraid the 'boom' would vanish like the morning dew if there were major funding cuts in 2015."

For kids, museums have a mystic magnetism. From terrifying dummies wearing military costumes to models of knights chopping into an enemy in the gift shop; the more macabre, the merrier the child. Museums and galleries can fire small synapses: "They really have the ability to create personal memories and experiences that are unforgettable," believes 27-year-old Melany Rose. Rose works in education at London's Foundling Museum, and is part of a new, artistically inclined generation making museums less stuffy. "You can't forget the first time you looked at a painting or had an artistic experience that brought you an intense emotion, or learnt about an object that held a story that you could relate to. These personal connections give us the chance to create meaning in a unique way."

For anyone who went to school in Norfolk (myself included) one memory burns bright: the former Gressenhall workhouse near East Dereham – a school trip designed to make you put down your GameBoy and realise you'd never had it so good. "I also went there as a > child," remembers Rose. Children are made to dress as Victorian kids, endure the country cold, and absolutely not write left-handed. I ask Norfolk Museums service director Steve Miller about the place today. "Gressenhall is just about to embark on a major capital development," he says, adding: "Despite the financial pressures on all museums, I think that in Norfolk, our museums are moving into an incredibly exciting era."

Perhaps the reason the number of museums is expanding so rapidly, is that we're creating more and more stuff which needs to be remembered.

Look at the lorries, the freight trains, the container ships, the big distribution sheds scarring the edge of every town near a motorway. There's so much stuff today. What should we put in museums of the future? "Recently, the V&A has been trying to be more engaged and responsive to what goes on outside – in exhibitions like Disobedient Objects and our new Rapid Response collections," explains V&A director Martin Roth. The latter, notably, included the world's first 3D-printed gun. "We're also more open about what goes on behind the scenes, which goes some way to breaking down barriers," he adds, "as, of course, does free entry." The National Gallery, British Museum and Tate never charged, but since 2001 the Natural History Museum, V&A and many others have scrapped charges, too. A brave and brilliant move.

Today, some museums and galleries are brands. They've begun colonising in the way that countries did while the institutions themselves were being formed, back in Victorian days. Galleries have flocked, in particular, to aspirant port cities searching for sophisticated visitors: the Tate to Liverpool, Guggenheim to Bilbao, and next summer the Pompidou to Malaga. The V&A is heading for Dundee; the Louvre and Guggenheim to Abu Dhabi – though the lowly status of builders working on the latter two leaves a sour taste. One port that isn't so keen is Helsinki. It's full of beautiful, polite people, of solid-footed buildings, crisp design and a highly developed hermetic culture. It is the last place on Earth in need of 'regeneration'. "The global spread of branded museums risks, like the diffusion of other branded product from Starbucks to McDonald's, both a suffocatingly uniform and money-driven art – no town without its balloon dog! – and the suppression of indigenous scenes." These are the thoughts of Michael Sorkin – New York architect, architecture critic of The Nation magazine, and judge of a competition set up to find a building for the site in the Finnish capital other than a proposed Guggenheim. Sorkin adds: "The metric for the success of these places – numbers of visitors, collateral benefit to the tourist industry, robust sales in the gift shop – is precisely not what art should be measured by."

In Britain, we draw a distinction between galleries and museums that some other countries, notably the US, do not. Think of New York's famous Museum of Modern Art. Art is deliberately created. If it's done right, it turns a meaning the artist has given it into a feeling in the person looking at it. An object is created for different, often more practical reasons. It can still provoke a feeling though. Should we continue to segregate 'art galleries' from 'non-art museums'? "I see a convergence between what have traditionally been called 'art galleries', 'history museums' and 'science centres'. By this I mean that art, objects and interactivity, all underpinned by robust academic research, will be used collectively to engage visitors with the important topics of the day," says Sharon Ament, director of the Museum of London. "Our challenge is to enable people to see and feel art in ways that maintain the primacy of that experience. Really looking at art is something that takes time and needs to be repeated; it would be nice to think that we can foster this kind of looking alongside the excitement of the one-off event," says Penelope Curtis, director of Tate Britain. "Looking at art slows us down and takes us in unexpected directions: this is increasingly unusual – and something people cherish."

Despite being swamped by possessions, we've changed our views towards those things. The triumph of experiences over objects presents prickly dilemmas for Britain's museums. In the second half of the 20th century, people defined themselves by what they had. But today people increasingly define themselves by what they do.

Museums represent the last gasp of high culture in an age where showiness and novelty and thinness – even in the arts themselves – threatens to overwhelm us. The V&A's Martin Roth complained to the Financial Times in September about "the quality of contemporary art... [which] is 95 per cent > rubbish." Museums are a bulwark against dumbing down and against the commercialisation of everything. Art and education, not money and the stuff we can buy with it, are the things that lift us from being working people to being civilised people. Museums and galleries democratise this idea. They are places for everybody. You don't have to own the Rothko painting or the Barcelona chair. Mostly, you don't even have to pay to get in.

As the age of social media encourages a sort of digital narcissism, are we unintentionally curating museums of our selves? With our entire histories catalogued by Silicon Valley corporations.

In the near future, patrons might demand nothing less than personalised museums. The virtual, or even perhaps real, museum of John or Janet or Apple-Pie Smith. A museum of ourselves where everything is tailored to the most important subject of all. A first tooth, a first painting, a first mix tape, a first love letter, a mock-up of the first of a lifetime's worth of many rented rooms, a neuroactive pill you can pop to magically take you back to your first high at a music festival in a muddy field, a first wedding ring, a second wedding ring, a first child's first tooth. These museums of the individual could be the places future generations will head to learn about Grandma Apple-Pie's crazy life in the swinging 2060s.

"The tension in reconciling what the museum feels duty-bound to present with what consumers show that they want is likely to lead to an even greater emphasis on entertainment," believes Tim Reynolds, director of the National Museum of Computing. Let's hope we don't see a Museum of Facebook statuses any time soon. "The shared physical experience of museum-going is powerful, it's what attracts audiences in a digital world," ponders Deyan Sudjic – former architecture critic of The Observer, and latterly director of the Design Museum. "The digital and the physical will blend. The key will be storytelling to animate objects – rather than mute collecting." Museums and galleries will find ways to do this. They have to – they're not just days out, they're the very distilled essence of civilisation.

As Nina Simon, author of the book The Participatory Museum, and director of Santa Cruz Museum in California, reminds us, "Museum artefacts tell the stories of what it is to be human: to fight, to love, to strive, to suffer, to play"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments