Why the hair on our head should be more than merely decorative

In Asia, human hair is sold and recycled, but in the West it is treated with disgust or veneration

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hair grows spontaneously from our heads naturally, but is rarely left in its natural state. Throughout our lives we spend time and money grooming it – cutting, shaving, curling, dying, straightening, covering, supplementing, or simply arranging.

Our hairstyles project our sense of identity and how we wish others to see us. Both seductive and demanding, hair is fraught with expectations and aspirations about beauty, identity, culture and race.

It offers creative possibilities, and can express conformity and dissent. But what does hair represent once removed from the head?

Our attitudes to human and animal hair are very different. We baulk at the idea of a dress or jacket made of human hair, but think nothing of wearing sheep’s wool jumper or camel hair coat.

Why is the trade in cat and dog hair banned in the European Union on the grounds that they are pets, while the trade in human hair remains entirely unregulated?

What sort of intimate hairy entanglements occur when we brush human hair with pig bristles, use badger hair shaving brushes, or weave a judge’s wig from horse hair?

Clearly our attitudes to these various fibres are not about their physical properties – they are all composed of keratin – but about how we carve up our conceptual categories of animal and human.

Our relationship to hair is explored in Hair! Human Stories, a new exhibition I have curated, in which we consider the role of hair as a raw fibre and as a material with potential for recycling into wigs, extensions, rope, art works and even clothes.

These ideas are explored through unexpected objects, such as a dress made of human hair by Jenni Dutton, a hair purse by Tabitha Moses, a tiered, hair wedding cake by Jane Hoodless, portraits of people wearing clothes made from their dogs’ fur, and a cat hair necklace made from the fur of my own cats. Visitors can touch and appreciate the different textures.

There is much about hair that is anomalous. Seen in piles, it is disturbing, perhaps calling to mind the piles of hair from murdered Jews in the Nazi’s death camps. As both a body part and a body product, it is what British anthropologist Mary Douglas famously classified as “matter out of place”.

When found on the head, hair evokes ideas of vitality, virility, femininity or seduction, but once removed it seems to evoke death. Yet hair has often taken on a disconcerting life of its own.

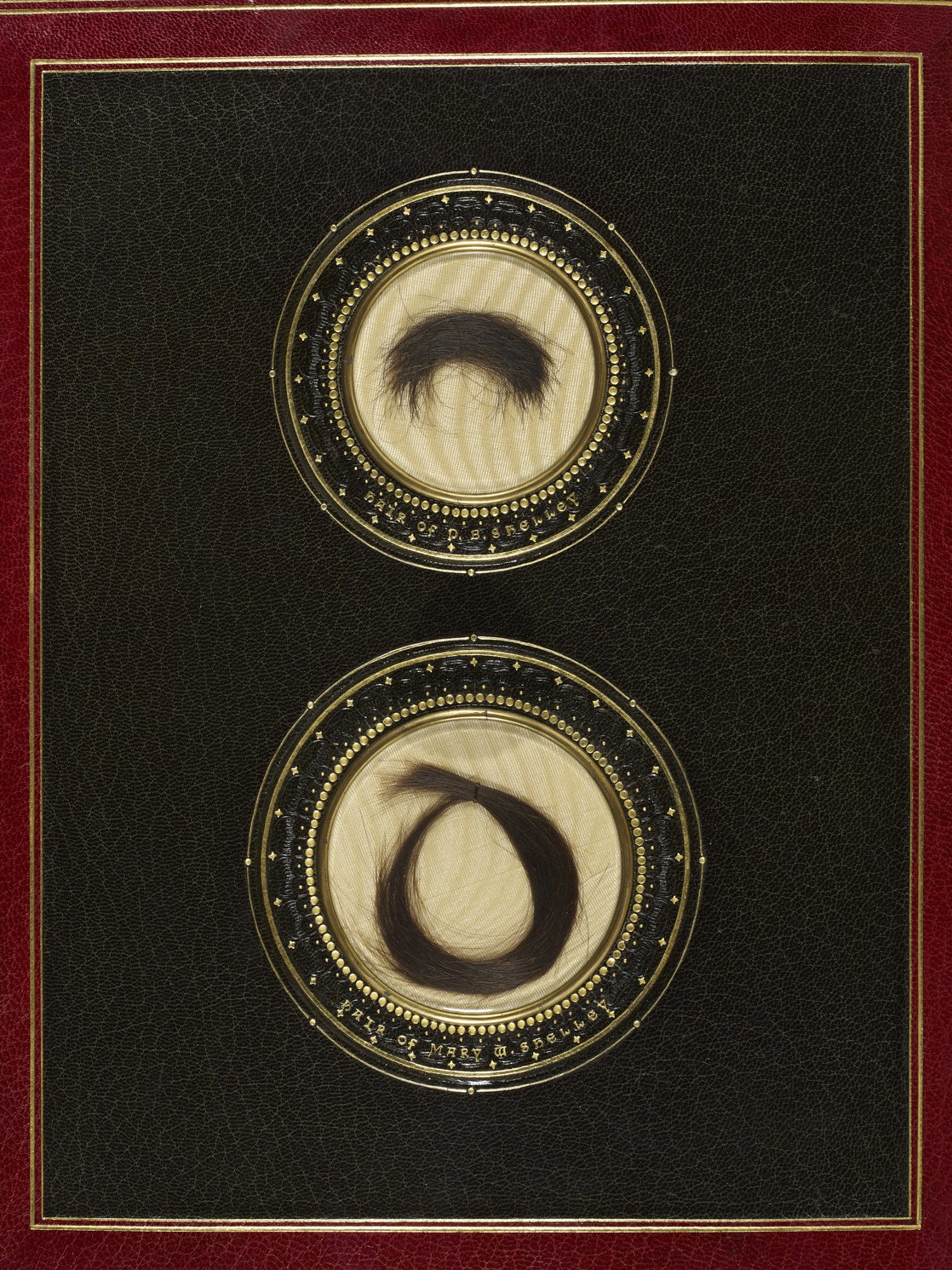

The Victorians were renowned for keeping locks of hair of lovers, relatives and the departed, sometimes lovingly stuck into albums or incorporated into jewellery. By wearing someone’s hair close to skin, intimacy could be maintained.

Collaborating with my local hairdresser, Hacketts, I’ve collected hair from over 30 people along with comments about their feelings towards their hair.

The exhibition also contains the long auburn hair of a mother and daughter, one in the form of a bunch cut in the 1940s against her father’s will, the other in the form of a plait cut off in the 1970s – both lovingly kept wrapped up in scarves.

For some people the act of offering hair clippings triggered memories of their love-hate relationship with their hair, such as the journalist Isabel Berwick’s struggles with her curly hair.

Hair is not something people like to throw away. To chuck out a hair clipping from a mother, grandchild or baby feels like an act of violation. Personal identity seems to linger on in hair even after it has been removed from the head.

It is no surprise then that in many cultures hair has been used in magic, the idea being that a person can be harmed through manipulating something that was once a part of them.

And yet every day our hair leaves us. On average we shed between 50 to 100 hairs a day. This means that the more hairy among us shed over 30,000 hairs a year.

In most of Europe fallen hairs are ignored unless a person is suffering from alopecia or some other form of hair loss and, even then, we are more likely to pay attention to its absence from the head than to where the hair once detached ends up.

But this is not the case in many parts of Asia, where long-haired women carefully collect up hairs that fall out during brushing or washing because such “combings” have a market value.

In India, 100g of dusty hair balls sell for 100 rupees (about £1). In many Asian countries hair peddlers travel on foot, by bicycle or boat, door-to-door collectors of waste hair, which they sell to traders who export it to hair untangling workshops, situated in some of the poorest regions.

In the exhibition we see pictures of women and teenagers painstakingly untangling, sorting, de-licing and combing the hair for upcycling into products such as wigs.

Combings are just one strand of the hair market: hair also comes from women who sell it directly into the trade, or through donations made for religious or charitable reasons.

Once gathered into perfect bunches it is sent to hair factories in China and used for making the cheaper range of wigs and hair extensions for the world market.

Unlike the cherished hair kept in families, this hair becomes entirely stripped of its personal and cultural associations.

It even gets assigned new identities – marketed and sold as “Brazilian”, “Peruvian” or “European” as it is bleached, dyed and refashioned to suit different tastes in the global market.

By the time the hair becomes attached to new heads it has generally travelled thousands of miles, passed through many hands and been subjected to many processes.

In its new incarnation it becomes re-personalised and invested with human aspirations of beauty, ethnicity, religion, health and glamour. Hair – though a fibre composed of dead matter – is nevertheless saturated with human life and emotions.

Given hair’s importance to us, and its extraordinary strength, flexibility and durability, it is surprising that we make no use of this natural resource in the West.

Every year in the UK alone 6.5 million kg of hair enters the waste stream. Ecologically minded designers and their creations, such as Sanne Visser’s hair rope, Alix Bizet’s hair hoodie, or the US organisation Matter of Trust’s approach of using waste hair to soak up oil spills, suggest the potential for making better use of our ubiquitous human fibre.

is a professor in anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London. This article was originally published on TheConversation.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments