Happy 30th anniversary Poems on the Underground; week in books column

Thanks for minding the gap, Judith!

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a fiercely cold morning this week, I found myself standing inside the usually shut Aldwych Station in central London, dunking iced doughnuts into my hot chocolate, with a small crowd of others who listened to poetry being read out loud. The gathering had an illicit, Platform Nine-and-Three-Quarters feel to it, as if we’d all been accidentally locked in to a poetry slam overnight, or had discovered a new, secret realm of lyrical commuters.

Catherine Heaney, Seamus Heaney’s daughter, stood over a microphone, just left of the defunct ticket office, reading her father’s “The Railway Children”. Adrian Mitchell’s widow read “Celia, Celia”, a poem written by him in her name, which brought a salty laugh when we heard its earthy finish: “When I am sad and weary/ When I think all hope has gone/ When I walk along High Holborn/ I think of you with nothing on”.

The man from Transport for London chose one about fathers by Patrick Kavanagh that brought tears to my eyes (“Every old man reminds me of my father...”) while the Guyana-born poet Grace Nichols read one she’d written 35 years ago, on coming to London, of homesickness for her mother’s food (“...I leave art galleries/ in search of plantains/ saltfish/ sweet potatoes”).

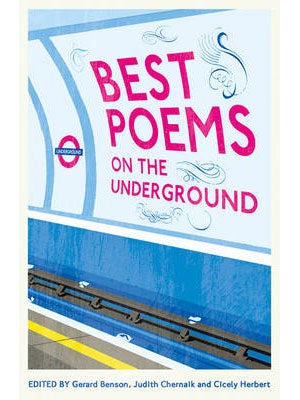

And so many more, one poet after another, reading long, short, moving poems that had a note of familiarity to them. All because Judith Chernaik had sat on a Tube 30 years ago to the day, looked up at empty advertising space and thought, “wouldn’t it be nice if a poem were up there”. Judith – clearly a woman of action – (“well, I’m a New Yorker!”), went home and “wrote a letter into the void”. The boss of London Underground wrote back, as miraculous as that sounds, and took her up on her idea to plaster poems on Tube hoardings. And so the now treasured institution, Poems on the Underground, was born in London and then cities around the world.

Talking to Judith was inspiring. She and her committee choose poems that support her belief that poetry is not elitist, but speaks to everyone. It is, after all, the earliest art-form we learn, as rhymes and songs. The scheme has boosted the profile of emerging poets and combined old works with new to show the trajectory between tradition and invention.

What struck me as most extraordinary about Judith and her crowd was the sense of activism they embodied. She joined up with two Barrow Poets of the 1970s and together, they made the idea happen. Poetry to them, she tells me, was entertainment, to be read out or performed in pubs, but also something that had a serious and anti-establishment edge.

There is something so ingenious in the idea to put poetry into such an ordinary, workaday space too. For someone like me, with an early love of prose but an equally early suspicion of poetry for being too bourgeois to relate to, the first Underground poem I read as a teenager – lines from Keats’s Endymion – got me thinking that poems might be relevant after all, evocative enough to make me sit up and laugh or feel sad, puzzled, or happy, on the Northern line – which is no mean feat.

Someone at Aldwych thanked Judith for creating a purely good thing, adding, “there are not many of those”. True, and yes, thanks!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments