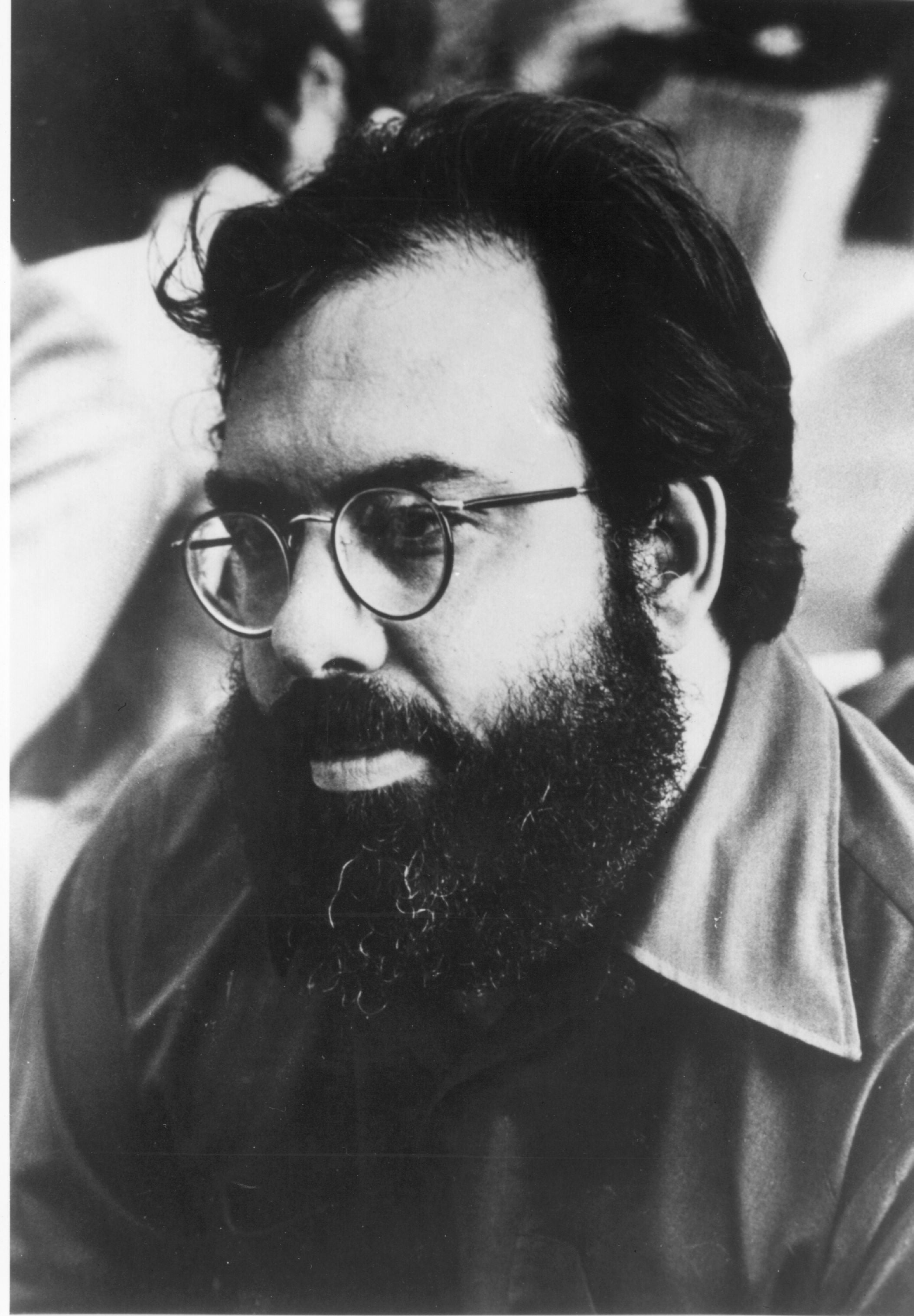

‘My daughter took the bullet for me’: Why Francis Ford Coppola is restoring The Godfather Part III

Just when he thought he was out, they pulled him back in – Francis Ford Coppola has returned to the troubled Godfather Part III with unfinished business. He spoke to Dave Itzkoff about how it all came to be

In the final scene of The Godfather Part III, Michael Corleone, the aged protagonist of this epic crime drama, is left in solitude to contemplate his sins, gripped with guilt over actions that have devastated his family and the knowledge that he cannot change what he has done.

Francis Ford Coppola, the director and co-screenwriter of the Godfather series, has never approached his work in quite the same way. These three movies have won a combined nine Academy Awards, grossed more than $1.1 billion (£826m) when adjusted for inflation and gained an exalted status in the popular consciousness. But rather than regard them as immutable monuments, Coppola has treated them like an unfinished painting he is free to update.

He has previously restored and reordered portions of the Godfather story, modifying its multigenerational tale of corruption, vengeance and family duty as his own ideas about storytelling have evolved.

Now he has turned his attention to The Godfather Part III, the 1990 film that took a more meditative approach to the Corleones. Unlike the near universal acclaim the first two movies enjoy, Part III is remembered as the Fredo of its family — the one that doesn’t really measure up. It was criticised for its lugubrious tone, convoluted plot and Coppola’s casting of his daughter, Sofia — now a celebrated filmmaker in her own right — as Michael’s doomed daughter, Mary.

For a new theatrical and home-video release this month, Coppola has rechristened the film as Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone. The new name pays tribute to Puzo, his Godfather co-screenwriter and author of the original novel, and includes the title they originally intended for the film that became Part III. The director has changed its beginning and ending and made alterations throughout to excavate and clarify the narrative that he always believed it contained about mortality and redemption.

The history of this Godfather movie is as sweeping and dramatic as the much-told tales behind the creation of its two illustrious predecessors, full of conflict, perseverance and decisive last-minute changes. It is a legend that seemingly ended with a fatally flawed result — but now has a new untold chapter that could improve the standing of the final film in one of the most influential franchises of all time.

Coppola’s personal story is of course inextricable from the story of the movie, and there is more at stake for the director than reclaiming his movie from the tarnished reputation he felt it never deserved. At 81, he is still striving to demonstrate his vitality as a filmmaker and reconnect with the rebellious energy that permeated the making of the first two Godfathers.

He is no longer the barnstorming artistic despot of the 1970s; these days he approaches his trade like a seasoned craftsman, always honing his work in search of some mythical ideal. Using a quaint metaphor, he compared his process to fixing a cigarette lighter.

As Coppola explained in an interview, “You put in more fluid. Then it’s too much fluid, so you have to put in a new flint. You have to pull the wick out. And then, all of a sudden, it lights.”

Coppola never intended to make even one sequel to The Godfather, his blockbuster 1972 adaptation of Puzo’s bestselling novel. But he said he had been seduced by Paramount, the studio behind the films, which acceded to his demand to give the initial follow-up the then-unusual title of The Godfather Part II.

Already, Coppola said, Paramount had visions of building the original runaway hit into a multi-movie franchise. As he explained the studio’s philosophy, he said, “You’ve got Coca-Cola, why not make more Coca-Cola?”

When Part II, released in 1974, unexpectedly matched the critical and commercial acclaim of its predecessor, few of Coppola’s colleagues believed that he was interested in risking his luck on a third instalment. “I always thought Francis was done with it,” Al Pacino said. He himself was ready to leave behind his career-making role as Michael Corleone. As he put it in a recent interview, “I felt a little tired of doing that kind of thing. It was consuming.”

The studio nonetheless continued to develop a third Godfather and courted Coppola, who had moved onto ambitious projects such as Apocalypse Now. But in the 1980s, his costly misfires, such as One From the Heart and The Cotton Club, made Paramount’s offer one that he — well, you know how the quotation goes.

“I was in much less of a strong position,” Coppola said. “Frankly, I needed the money, and I was coming out of a real financial doldrum where I had almost lost everything.”

Another incentive for Coppola to return was to team up again with Puzo, his esteemed screenwriting partner, and compose the script for Part III: one branch of the story would follow a new family member, Vincent (played by Andy Garcia), an illegitimate child of Michael’s brother Sonny, as he tries to earn his place in the Corleone clan, while another branch would chronicle Michael’s efforts to buy his way to legitimacy and absolution.

But in Italy, the film faced a serious crisis. Ryder, who had just finished shooting ‘Mermaids’ in Boston, became ill when she arrived in Rome

Pacino was delighted by the screenplay, in which Michael’s well-honed craftiness would be tested by unexpected guile within the Vatican: “He found something a little more corrupt than his criminal world,” the actor said.

Though it would be decades before Coppola could call the film Coda, he already saw the project as such: “It was really our intention to make it a summing-up and an interpretation of the first two movies, rather than a third movie,” he said.

In September 1989 the Part III cast and crew gathered at Coppola’s Napa Valley vineyard to rehearse and prepare for filming. The roster included Godfather mainstays such as cinematographer Gordon Willis and production designer Dean Tavoularis.

As Coppola had toyed with the ages of the Vincent and Mary characters — first older, then younger — he had contemplated several actresses to play Michael’s beloved daughter: he had tested Madonna for the role and also considered Julia Roberts before casting Winona Ryder. Ryder was expected to arrive later in the process, so Coppola’s 18-year-old daughter, Sofia, stood in for her at this preliminary stage.

The production then moved to Italy, where the latter half of the film takes place, for an experience that some veteran members of the cast found almost indescribably sumptuous.

“For me, that was my favourite of the Godfathers, because I was happy and I really enjoyed who I was playing,” said Diane Keaton, who was Kay Corleone in all three films. “At the time, I was with Al. I was sort of his — I don’t know what you would call me — I guess I was his girlfriend. It was an amazing experience just to be there and partake.”

Coppola was working against a gruelling timetable dictated by Paramount, which wanted the movie for Christmas 1990, but the actors found him to be a meticulous and communicative director.

“When you were doing a scene with him, it wasn’t just, ‘OK, everybody, let’s rehearse and let’s go,’” Garcia recalled. “He takes his time to set up the world and the reasons why this scene exists and the objectives of why we’re here.”

Changes to the script were also commonplace. Citing an aphorism he’d heard from Tavoularis, Garcia said, “With Francis, the script is like a newspaper — it comes out every day.”

But in Italy, the film faced a serious crisis. Ryder, who had just finished shooting Mermaids in Boston, became ill when she arrived in Rome and withdrew from the film. Reports from that time said that actresses such as Annabella Sciorra and Laura San Giacomo were suggested as possible replacements; today, Coppola would say only that: “Paramount had a list of many fine actresses who were older than I felt the character should be.”

“I wanted a teenager,” he said. “I wanted the baby fat on her face.”

Instead, the director saw his solution in Sofia, who was visiting the set on a break from her freshman year of college. She had appeared in several of her father’s previous films, including Rumble Fish and Peggy Sue Got Married, and knew his rhythms and shorthand.

Sofia Coppola said her decision to take the part was straightforward and organic, undertaken as an act of goodwill to her father.

“It seemed like he was under a lot of pressure and I was helping out,” she said. “There was this panic and before I knew it, I was in a makeup chair in Cinecittà Studios in Rome having my hair dyed.” But she trusted her father’s judgment and felt safe among his collaborators. “For me, they were all my family,” she said. “It felt very separate from the outside world.”

Talia Shire, who played Connie Corleone and is the director’s sister, said that Sofia’s involvement reinvigorated her father at a crucial moment.

“It was a stressful time,” Shire said. “Her being in it and his focus on sculpting her performance kept him connected to the piece. His passion for it returned.”

But amid the whirlwind that swept her up and dropped her in front of her father’s cameras, Sofia Coppola said she never considered the wider ramifications that her choice might have. “I wasn’t taking things super-seriously,” she said. “I was at the age of trying anything. I just jumped into it without thinking much about it.”

The Godfather Part III was scheduled for release on December 25, 1990. Critical reactions were as extravagant as the hype surrounding it, and some reviews were glowing: The New York Times called it a valid and deeply moving continuation of the Corleone family saga that offered Coppola the opportunity to regain a career’s lost lustre. Many other notices were not just negative but scathing: The Washington Post said the film wasn’t just a disappointment, it was a failure of heartbreaking proportions, adding that it sullied what came before.

They wanted to attack the picture when, for some, it didn’t live up to its promise, and they came after this 18-year-old girl, who had only done it for me

A particular strain of criticism focused on Sofia Coppola’s performance as Mary, who dies in a botched attempt on Michael’s life. The Post called her hopelessly amateurish, and Time magazine wrote that her “gosling gracelessness” came close to wrecking the movie. Gene Siskel said in a TV review that she was out of her acting league.

For Sofia Coppola, the cultural whiplash was bewildering; she had been asked to take part in glamorous photography shoots for magazines such as Entertainment Weekly, only to find herself on their covers surrounded by headlines like: “Is She Terrific, or So Terrible She Wrecked Her Dad’s New Epic?”

Looking back on the ordeal, she said: “It was embarrassing to be thrown out to the public in that kind of way. But it wasn’t my dream to be an actress, so I wasn’t crushed. I had other interests. It didn’t destroy me.”

Part III grossed more than $136m worldwide; it was nominated for seven Oscars, but won none. Francis Ford Coppola, already smarting from the negative reviews, was further stung by what he saw as efforts to make Sofia a scapegoat for its shortcomings and blamed himself for putting her in that position.

“They wanted to attack the picture when, for some, it didn’t live up to its promise,” he said. “And they came after this 18-year-old girl, who had only done it for me.” The story he had just told in the movie provided an irresistible metaphor: “The daughter took the bullet for Michael Corleone — my daughter took the bullet for me,” he said.

Decades went by, during which Coppola continued to rework his past films, including the first two Godfather movies, Apocalypse Now and The Cotton Club. He also shed some of his pride and became a humbler person. If his name evokes the mental image of a burly, bearded, sometimes bare-chested beast working a camera in a southeast Asian jungle, he and his beard are thinner now, and his manner is more deferential.

He is aware of the chequered reputation of The Godfather Part III and that no amount of changes might be enough to redeem it in the eyes of some viewers. As he told me in a video interview from his Napa estate: “When a movie is first made and is about to be released, you know that whatever the reaction is will define it for its entire life.”

There were things about the movie that irked him, too, starting with the Part III title he was compelled to accept. “It was the thread hanging out of the sock that annoyed me, so that led me to pull on the thread,” he said.

He realised that the opening in the film’s theatrical release — which mixes footage of the Corleones’ Lake Tahoe home seen in Part II with a mournful voice-over from Michael — made it difficult to grasp what the story was about. As he told me: “The audience goes into a film with a certain amount of resources. They’re willing to go with you, but there’s a limit.”

The Godfather, Coda now begins with a scene that came later in Part III, when Michael is negotiating a multi-million-dollar deal, involving the Vatican Bank and a real estate company, with the desperate Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly). The aim of this change, Coppola said, was in part to more closely parallel the opening of the original Godfather, when Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) hears the angry pleadings of a wronged undertaker.

Starting this way immediately establishes the stakes of the film, Coppola said. “You get it put right to you: What is the big deal about? The Corleones have reached such a level of success and wealth that they’re able to loan money to the Vatican.”

Coda has other nips and tucks throughout — you’ll see less, for example, of Don Altobello, a supporting character played by Eli Wallach — but the other significant change comes at the conclusion. (Turn away here if you don’t want it spoiled for you.)

Where Part III ended famously — some might say notoriously — with the elderly Michael slumping in his chair and falling dead to the ground, Coda shows him old and alive as the scene fades to black and a series of title cards appear. They read, “When the Sicilians wish you ‘Cent’anni’ ... it means ‘for long life.’ ... and a Sicilian never forgets.”

Despite a new title that promises otherwise, Coppola explained that Michael does not actually die. “In fact, for his sins, he has a death worse than death,” he said. “He may have lived many, many years past this terrible conclusion. But he never forgot what he paid for it.”

Pacino said he enjoyed his preparations for Michael’s original death, an approach that was criticised as exaggerated and unintentionally comedic. “That was just fun to do,” Pacino said. “I spent hours, days, weeks, thinking, how am I going to die? It’s fatalist. I love dying. What actor doesn’t?”

But ending the movie as Coppola does now, with Michael stranded in a purgatory of his own making, felt right, Pacino said. “Leaving him awake, not dying, that’s the tragedy of it all,” he said.

I felt a sense of completion after the first one. I felt the first film had all the story I saw in the book

Perhaps his only regret, Pacino said as his voice rose to an exaggerated volume, is that he cannot do the scene again when he is finally as old as Michael is meant to be: “I’m ready to do it now!” he exclaimed. “I understand it better! I don’t need makeup!”

By introducing a note of ambiguity, Coppola and his actors are aware of the familiar questions they are opening themselves up to: Could there be further Godfather movies to come? Could Michael Corleone still factor into someone else’s future schemes?

“It looks that way now, doesn’t it?” Pacino said teasingly. “Somebody’s going to come calling on him for advice.”

Garcia has grown accustomed to disappointing fans who expect concrete answers to these inquiries. “Not a week goes by that someone doesn’t come to me and say, Hey, man, where’s Godfather IV?” he said. “I say, I’ll let you know when I get the call.”

But running jokes aside, it is highly unlikely that these key players would go forward without Coppola’s involvement, and he has made clear that he wants to move on.

The director said there were discussions, many years ago, about a potential fourth film — as he imagined it, it would have continued the story of Vincent in the present day and returned to the story of Vito and Sonny in the 1930s — but Puzo’s death in 1999 foreclosed that possibility.

This does not prevent Paramount from making sequels if it wants to. “There may well be a Godfather IV and V and VI,” Coppola said. “I don’t own The Godfather.” (Paramount said in a statement: “While there are no imminent plans for another film in the Godfather saga, given the enduring power of its legacy it remains a possibility if the right story emerges.”)

For others who participated in Part III, parts of the movie still hold up with the best of the trilogy, in their estimation, and its perceived flaws don’t seem as bothersome over time.

“It taught me that as a creative person, you have to put your work out there,” Sofia Coppola said. “It toughens you up. I know it’s a cliché, but it can make you stronger.”

Just a few days earlier, her teenage daughter, Romy, told her she had read about her mother’s much-discussed performance. “She said, ‘I saw online that you did the worst death scene ever in the history of movies,’” Sofia recalled. “I was like, oh my God, all these years later, it’s still a thing.”

With a laugh, she added: “I think it’s so funny that it lingers, all these years later. It’s fine.”

For Francis Ford Coppola, the fact that he has probably put his final stamp on the film series that altered his life and influenced moviemaking for decades to come is not an occasion for nostalgia or celebration; it’s just a reminder that there are so many more kinds of movies he still wants to make and genres he wants to play in.

“I like life to be an experience that I learn from,” he said. “I felt a sense of completion after the first one. I felt the first film had all the story I saw in the book. I felt satisfied that it was summed up.”

If there are more Godfather movies to come, he said, “I won’t do ’em. But I’m an old man.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks