'Who needs another Aids movie?' The crisis isn't over

The Aids epidemic of the 1980s may be gone, but the memories of the ones we lost aren't. An Aids crisis film pays tribute to sufferers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

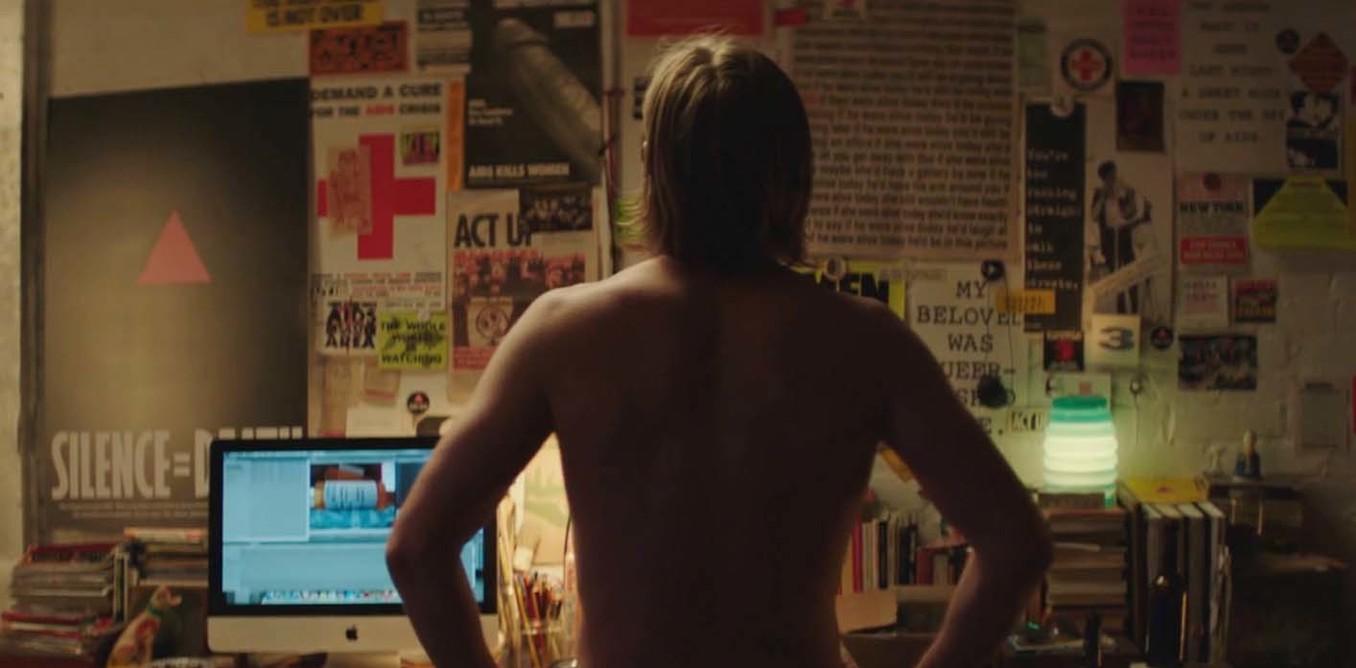

Your support makes all the difference.Vincent Gagliostro’s debut feature film After Louie, which had its world premiere at this year’s BFI Flare, encapsulates the generational tension in today’s “gay community”. It tells us the story of Sam (Alan Cumming), a chain-smoking middle-aged painter working on his first film project: a video memoir about the Aids crisis and a tribute to his long-term partner, who passed away during the early 1990s. It centres on Sam’s unfolding sexual friendship with Braeden (Zachary Booth), an HIV-negative millennial who lives in an open relationship with HIV-positive Lukas (Anthony Johnston).

At the core of the film lies a divide familiar to the two generations of gay men in so-called “post-Aids” societies: between those who lived through the peak of the Western Aids crisis in the 1980s and early ‘90s, and those who started living sexual lives with HIV no longer a death sentence. While Sam thinks Braeden’s generation has it too easy, Braeden angrily retorts: “Who needs another Aids movie?”

Sam’s film project places him alongside other real-life filmmakers who have been responsible for the recent wave of film and television productions that, in a more or less fictionalised way, tell the story of the Aids crisis as it happened. The emphasis here being on “happened”, on something that belongs in the past. In a memorial-like gesture of remembrance, Sam’s work resonates with real documentaries and dramas such as We Were Here (2011), Don’t Ever Wipe Tears Without Gloves (2012), How to Survive a Plague (2012), Dallas Buyers Club (2013), or The Normal Heart (2014). Like them, it firmly locates the Aids crisis in the past. In doing so, it aims to pay homage to those who have fallen, and to invite us to find closure and move on with our lives.

But then there’s Braeden, standing in for the newer generation who, unburdened by ghosts of the past, rediscovered a new sexual freedom thanks to modern methods of TasP (Treatment-as-Prevention) and PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis). While TasP means HIV-positive individuals cease to be contagious once they’re on treatment, PrEP allows HIV-negative people to avoid infection if they start taking similar drugs. So for those like Braeden, the film tells us, life has mostly become a joyful celebration of sex, sexuality and intimacy unbridled by illness or even monogamy. So far so ideal.

The limits of memorials

But neither of the two positions in the real-life conflict dramatised by the film is without problems. When it comes to Aids films, one must ask what it means to memorialise. What does it mean to set something into stone, metal, or moving image? What does it mean to seek closure by watching the films, visiting the memorial sites, and sharing selfies on social media? What does it achieve beyond nostalgia for a supposedly lost sense of “community”, and to firmly locate the Aids crisis in the past?

Remembering, making something “past”, getting over it, closing a chapter, getting even, seeking redemption: those are the ways of closure. And although closure can help certain individuals at certain times, expecting or even requiring closure also comes with issues. It tells us how we should feel. The problem with this is not how it promises the end of pain (for obvious reasons), but rather the way in which, through selling and expecting closure, popular narratives on mourning and overcoming trauma, whether personal or collective, can also be used to mask ongoing struggles.

The increasing numbers of film and TV productions dealing with Aids in the past also implicitly tell us that the traumatic event has been lived, that it has ended, and that it is now our job to move on and get closure. By asking us to remember, they risk overlooking the pain of those still living. Through focusing on the past of Aids, they glance over the present battles in the fight against HIV and Aids, presenting them as anachronistic events, as aftershocks, as negligible leftovers of the real thing.

This isn’t over

Which leads us to Braeden’s character and the supposed “easy” life enjoyed by the newer “post-Aids” generations. Who exactly are these younger men who have purportedly been given a “get out of jail free” card?

With no decline in new HIV infections worldwide since 2010 and only 46 per cent of all people living with HIV having had access to treatment in 2015, with Aids-related deaths still dominating most of the planet south of the Equator, with PrEP still unavailable on the NHS, and stigma and discrimination still a feature of everyday life for many living with the virus – including in the UK – one cannot but interrogate who exactly is being allowed a free and easy life. Many are instead still living in fear of prejudice, rejection, and even death.

Different population demographics across the world are being affected by the virus differently through unequal access to support networks and effective forms of prevention, risk management and treatment. So how politically productive and accurate is it to tell stories of a “gay community” divided between those who struggle to mourn the past, find closure and get over it, and those for whom HIV barely means anything beyond taking a pill a day? Perhaps we are engaging in remembrance and closure rituals too soon.

We must ask ourselves who is being remembered, who is being given the privilege of remembering, and who these memorial sites and narratives serve. Who has not yet been given the chance to become visible and accounted for, let alone have their stories told?

ecturer in history of modern and contemporary art and visual culture at the University of Exeter. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments