The madcap film career of Salvador Dalí: From Buñuel to Hitchcock to Alka-Seltzer adverts

Thirty years after his death, Martin Chilton remembers the father of Surrealism’s curious forays into the moving image

Salvador Dali, a pioneer of European Surrealism, was one of the best-known artists of his generation, a visionary who explored the depths of the subconscious mind. His paintings were full of the fantasies, dreams and hallucinations that were a product of an enigmatic and highly original imagination.

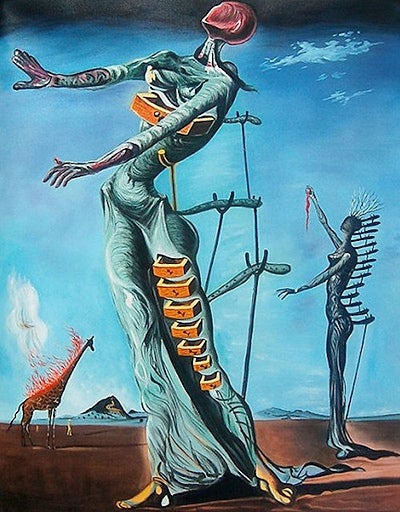

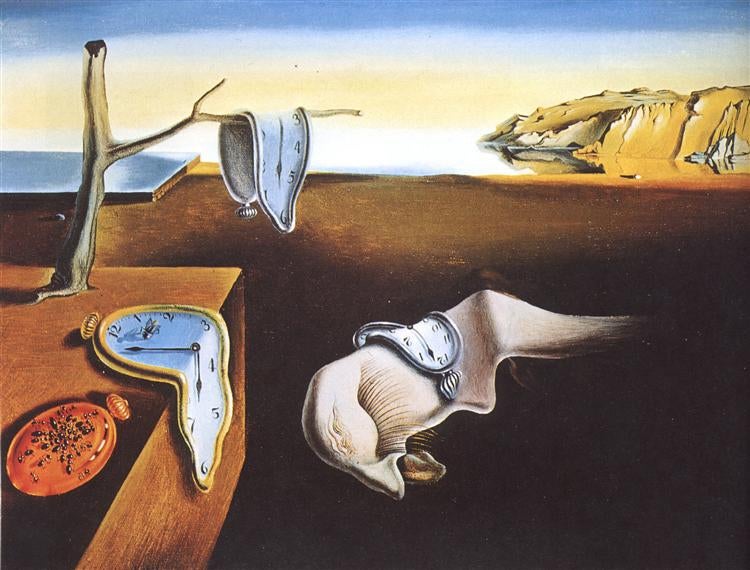

The Spaniard, who died on 23 January 1989 at the age of 84, produced Surrealist masterpieces in the 1930s – such as The Burning Giraffe and The Persistence of Memory – that influenced a generation of artists. His use of unusual imagery and symbols – keys, staircases, dripping candles, ants and scissors, for example – reshaped the artistic landscape. “Pop art is very much based on a lot of Dali’s work,” said Jeff Koons, one of a host of modern painters inspired by Dalí.

Dali had a flair for publicity and scandal that meant he was rarely out of the news. What is less well known, however, is that he had a lifelong passion for film and, with characteristic inventiveness, came up with some of the weirdest ideas in Hollywood history.

A trip to the movies might have been a more bizarre, interactive experience if the Spaniard’s concept for “Le cinema tactile” had got off the ground in the 1930s. Dali drew elaborate sketches for his tactile cinema, showing how objects and artefacts would slide out of the back of a cinema seat, enabling viewers to touch items that were being presented on the screen.

While he was involved in the production of the movie L’Age d’Or, for example, he proposed that cinema-goers would be presented with rubber breasts to fondle while they watched a scene in which a woman was being caressed. He also suggested that hot water should be sprayed on peoples’ hands just as a bidet was being flushed in the movie. Needless to say, this oddball idea was not a viable commercial proposition.

Dali’s passion for cinema was genuine. The Catalonian boy born Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dali Domènech on 11 May 1904 spent much of his youth at the local cinema in Figueres. As a youngster, Dali particularly enjoyed the slapstick comedy of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langton and the Marx Brothers.

It was his love of comedy that prompted one of his most eccentric notions. During a visit to America in 1934, he was trying to stir interest in funding for a film called “The Surrealist Mystery of New York” in which he planned to cast the comedian and musician Harpo Marx as a beggar with severed arms and legs.

His own start in the film world came about after a tumultuous time in the 1920s, when he was expelled from the San Fernando Academy of Art in Madrid for calling the examiners “incompetent”. He became interested in Surrealism and became friends with Luis Buñuel. Although Dali’s first solo exhibition in Barcelona had put him on the map as a young artist, he was persuaded to try his hand at film-making. In 1929, when Dali was 25, he collaborated with 29-year-old Buñuel on a silent movie called Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog).

The 17-minute surrealist film was intended to shock so-called respectable European society with its overt sexual and graphic imagery, especially the startling opening scene. Director Buñuel and screenwriter Dali devised a scene in which a cloud floating across a full moon in the night sky faded into a razorblade slicing through the eye of a young woman. They wanted to startle audiences, “to plunge like a dagger into the heart of Paris”, as Dalí put it. A cow’s eyeball was used for the actual slashing scene, which reportedly left Buñuel feeling sick for several days.

Weird images come thick and fast in the movie. Ants pour from a hole in a young man’s rotting palm; priests are dragged around; a dead donkey is draped across a grand piano. Dali was fascinated by the donkey and gleefully aided the state of putrefaction by gouging out the animal’s eyes and hacking at his jaws with scissors. The aim may have been to sicken and alarm, but audiences loved the film, which ran for eight months. The cinematography – including a scene in which a figure holding a severed hand in a box is shown from overhead – reflected the same desire to subvert and disrupt conventional perspectives that was a feature of Dalí’s art work.

“What comes through this film is the feeling that it would all make sense if its scenes were assembled in the right order. But of course it would not make sense, whatever the order, and I take this to be the point of the film,” said novelist JG Ballard. “The reality we inhabit daily, our domestic interiors and their emotional dramas, the hands helplessly caressing a young woman’s breasts, the tennis racket she uses to drive away her unwanted suitor (the surrealists were intensely middle-class), the small section of space-time we blunder through, are all equally unreal, though meaning and sanity seem tantalisingly within our grasp.”

The film’s cult status endured. When David Bowie staged his Isolar tour in 1976, he screened Un Chien Andalou at the start of concerts (instead of having a support act), much to the bemusement of some of his fans. Dali told the arts writer Mick Brown that he was a fan of Bowie’s music – and that he preferred Bowie to Alice Cooper. For a time in the 1970s, both Dali and Bowie had affairs with the model Amanda Lear.

In 1930, a year after Un Chien Andalou, Dali and Buñuel tried even harder to scandalise bourgeois sensibilities. The result was a screenplay for L’Age d’Or (Age of Gold), which was an attack on the “miserable mechanisms of reality” and the hypocrisies of middle-class life. However, Dali and Buñuel fell out during production and disagreed about the use of anti-Catholic images. The religious scenes caused an uproar and, at one early presentation of the film, fascists from the League of Patriots hurled purple ink at the screen. The film’s financial backers, the de Noailles family, were threatened with excommunication by the Pope and in 1934 withdrew all prints of L’Age d’Or from circulation. The film was not screened again until 1979.

In 1944, George Orwell wrote a long essay on Dali (“Benefit of Clergy”) which repeated a false claim about the film that had originated with writer Henry Miller. The author of Tropic of Cancer wrote an account of the film which claimed that there were explicit shots of a woman defecating. There were all sorts of sexual images in the film – including a woman sucking the toe of a statue – but Miller invented that detail. Orwell was simply repeating fake news.

The debacle over L’Age d’Or did nothing to damage Dali’s reputation in the art world, which was already soaring after his 1931 masterpiece The Persistence of Memory, with its iconic image of soft, melting pocket watches. Throughout the early 1930s, he produced works of startling originality, including House for Erotomaniac. After his 1934 marriage to his Russian muse, Gala, his work grew in boldness with paintings such as Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) in 1936 and Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937) gaining praise around the world.

Even with a busy painting schedule, he was still striving for success in Hollywood. “Throughout the 1930s he kept proposing new scripts to directors, although none of them really got off the ground,” said Dr Elliott King, author of Dali, Surrealism and Cinema. The artist met Harpo Marx at a party in Paris in 1936 and told him how much he loved Animal Crackers, a movie Dali described as “the summit of the evolution of comic cinema”. When Harpo returned to America, Dalí sent him a harp that was decorated with knives and forks and which had barbed wire for strings. In return, Harpo sent Dali a photograph of himself playing the harp with bandaged fingers.

Emboldened by his friendship with Harpo, Dali attempted one of his most ambitious cinematic feats – writing a film for the Marx Brothers. His 1937 screenplay, “Giraffes on Horseback Salads”, had scenes of animals wearing gas masks and being set alight. Dalí’s screenplay imagined Harpo catching dwarves with a butterfly net and Groucho cracking walnuts on the bald head of a dwarf. There was a giant eyeball which possessed 20 flailing arms. Dalí wrote a scene in which a dinner party is disrupted by a torrent of water that washes in a drowned ox. Some of the characters have to ride a bicycle as slowly as possible while balancing a stone on their head.

Harpo showed the script to Groucho, who joked later that “it would have been a great combination because Dali didn’t speak much English and neither did Harpo”. Groucho also said that Dalí wrote the film only because “he was in love with my brother – in a nice way”. In private, Groucho was scathing about the script and joined MGM Studios in vetoing the project.

When he was asked about the film in 1973, by the Marx Brothers’ biographer Joe Adamson, Dalí reacted by lashing out with his cane at some unfortunate nearby pigeons. “No one would dare to do Dali’s script,” the artist shouted at Adamson. Although he angrily insisted that Harpo “liked it”, he may have overestimated the degree of warmth in their friendship. The artist had once painted Harpo playing that famous barbed-wire harp and Adamson revealed that “Harpo and his wife stuck it in a remote corner of the house and finally threw it away”.

Dalí was not the sort of person to shy away from his ambitions and, despite the setback over the Marx Brothers film, he continued to court attention. In 1938, his stunt of wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet while delivering a lecture in London almost ended in suffocation. There was a natural wildness to him, which may explain why Sigmund Freud said, after meeting him in 1938, that he was struck by Dali’s “candid, fanatic’s eyes”.

Perhaps it was those fanatical eyes that convinced Twentieth Century Fox to consider commissioning Dali when they were making Moontide. The 1941 film, due to be directed by Fritz Lang, included a scene involving “a nightmare montage” which they thought would be ideal for Dali to create. Although the film was scuppered by the abrupt entry of America into the Second World War after the attack on Pearl Harbour, some of Dali’s script and storyboards for Moontide survive. In one sequence he envisaged a mammoth sewing machine.

Three years later, Alfred Hitchcock leapt at the chance to work with Dali on the thriller Spellbound. “I wanted Dali because of the architectural sharpness of his work ... the long shadows, the infinity of distance and the converging lines of perspective,” Hitchcock said in a 1962 interview with Francois Truffaut.

Ingrid Bergman plays a bespectacled psychiatrist who has to analyse the dreams of her amnesiac boss, Dr Anthony Edwardes (played by Gregory Peck), to try to prove he is not a murderer. Dali’s imagery was imaginative and splendidly odd: curtains painted with giant eyes are shredded by a man with a pair of enormous scissors; a man cheats at gambling with blank playing cards; Peck is chased by a giant pair of wings, beating overhead and casting ominous shadows. One proposal was a step too far, though. “Dalí had some strange ideas,” said Hitchcock. “He wanted a statue to crack like a shell falling apart, with ants crawling all over it. And underneath, there would be Ingrid Bergman, covered by ants! It just wasn’t possible.”

Dalí originally intended the dream sequence to last 20 minutes, although less than three minutes remained in the final edit. “The more I look at the dream sequence for Spellbound, the worse I feel it to be,” producer David O Selznick said in October 1944, a year before the film’s release. “It’s not Dali’s fault, for his work is much finer and much better for the purpose than I ever thought it would be. It is the photography, setups, lighting etc.” Despite the disappointment of his scene being truncated, Dali praised the director, saying: “Hitchcock is one of the rare personages I have met lately who has some mystery.” Bergman, with no ants to put her off, won an Oscar for her performance and the film was nominated in the Best Visual Effects category.

The year the film came out, Dali met Walt Disney at a dinner and was hired to work with the animator’s studio, creating storyboards for the seven-minute film Destino, which was based around a Mexican ballad by Armando Dominguez. Dali’s drawings feature a woman who undergoes surreal transformations into a floating dandelion. Dali described his technique of linking irrational images as his “paranoiac-critical method” and the approach is clearly recognisable in the film, which shows many of his famous motifs, including a melting face.

On Destino, Dali worked closely with John Hench, who was celebrated for his colour, background and styling work on Fantasia, Dumbo, The Three Caballeros, Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan. “My French was not much worse than Salvador Dali’s,“ Hench told Animation World Network’s website, ”so we got along fine and became friends. In spite of the bizarre images, Destino had elegance. You know in most of Dali’s great paintings, there’s an element that was closely associated with him, the way he dressed and his manners. He was pretty good at choosing angles and choosing any action, and then that would trigger another idea and he would jump on to that.”

Hench said they had such fun making the film, they even built a children’s toy kaleidoscope together during their breaks. Disney, who had spent about $70,000 on the project, gradually became more exasperated by the direction the film was taking, especially when Dali began to insert sketches of baseball players into the film. “It got a little too wild for Walt, so he quietly pulled the plug,” said Ted Nicolaou, curator of an exhibition at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco. “I think Dali was embarrassed and hurt by it.“

Despite the problems with Destino, Dali stayed in touch with Disney and tried to get further projects off the ground. In 1957, the artist even drew the figure of Don Quixote inside an edition of Shakespeare’s Macbeth in an attempt to reignite talks about a movie based on the famous character created by Miguel de Cervantes. In a happy postscript to the Disney interlude, Hench was asked five decades later by Roy Disney, the studio owner’s nephew, to resurrect Destino. When it was finally released, in 2003, it was nominated for an Oscar in the Best Short Film (Animated) category.

There were other successes – Dali’s famous sofa, covered in red satin, entitled “Mae West Lips”, inspired by the mouth of the wise-cracking actress remains an iconic piece of modern art – but on the whole nothing about Dalí’s career in the movie industry was ever straightforward. In Amanda Lear’s autobiography, My Life with Dali, the French singer says that, for a time in the late 1960s, Federico Fellini was interested in working with Dali but found him too “unreasonable”. Dali’s intransigence over money also caused a rift with Cubby Broccoli, who had hired him to design the deck of tarot cards to be used in the James Bond film Live and Let Die. Broccoli became angry at Dali’s exorbitant demands and replaced him with a little-known artist called Fergus Hall.

Undeterred, Dali still designed his own deck of 78 tarot cards, which went on sale in 1984 when he was 80. He used familiar motifs such as butterflies, roses, disembodied faces and ants. Death is a sinister skull in a floating cypress tree. His wife Gala was the face of the Empress card. Sean Connery’s face was on the Emperor card, despite the fact that Roger Moore had taken over the role of 007 by the time of Live and Let Die.

Although Dali’s film career dwindled in the late 1960s and 1970s, the artist was quick to grasp the appeal of television and the opportunity the medium offered to publicise himself to a vast audience. Dali admitted having a “pure, vertical, mystical, Gothic love of cash” and his exhibitionism and greed drove him to use his famous waxed, upturned moustache to endorse a host of products for French and American television commercials during this period. Dalí advertised cars, airline companies, medicines, chocolate and liquors. He was sometimes able to charge up to $50,000 for a day’s work.

In an advert for Braniff Airlines in 1967, he was filmed in a plane alongside baseball player Whitey Ford. Without a hint of self-consciousness, Dali proclaims the campaign slogan of Braniff. “If you got it, flaunt it,” Dali says in heavily accented English. “That’s telling ’em, Dalí baby,” replies the New York Yankees’ star pitcher. A year later, Dali appeared in an advert for chocolate, complete with animated moustache, in which he exclaims: “Je suis fou de chocolat Lanvin!”

Dalí also took part in an advertising campaign for the Datsun 180B/610 Wagon family car, even providing original artwork for print publications. The car he received in part-payment now sits among sculptures and works of art in the gardens of Dali’s castle in Pubol.

Perhaps his strangest ad campaign was for Alka-Seltzer heartburn tablets in 1974. Bob Cox, who worked on the advert, said that Dali was often surrounded by cross-dressers during filming and insisted that the music of German composer Richard Wagner be played on set. The artist also seemed to have little understanding of the 30-second time limit for the TV commercial. Dali assumed that the advert could be more than five minutes long if that was what he wanted.

In the end, the campaign ended in failure because of complaints about the content. “The opening scene showed Dali rushing across a stage to a girl and stabbing her with a giant marker,” Cox told Ad Week in 2007. “This was meant to dramatise the pain of heartburn.” The advert was greeted with outrage. “It was quickly pulled,” said Cox. The original footage for the advert resides in the Museum of Television and Radio in New York.

In 1975, director Alejandro Jodorowsky made a failed attempt to launch a film version of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune. The director wanted to cast Dali as the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV and met the artist in a hotel bar in Manhattan to discuss the role. According to Jodorowsky, Dalí asked for a fee that would have made him the highest-paid actor in Hollywood. The film was shelved and eventually made by David Lynch with José Ferrer playing Shaddam.

It is unlikely that Dali ever saw Dune. By the time it was out in 1984, Dali was suffering from depression and ill health and cut a lonely figure in Pubol Castle. In one low point, his incessant use of a call button for his care nurse caused a short circuit that started a fire in his bed, burning his leg. He died of heart failure and was buried in the Dalí Theatre-Museum, surrounded by some of his fabulous art.

Even if was just for that famous eyeball, Dali left his own indelible mark on cinema history, although it is a pity that the full craziness of a Salvador Dali-Marx Brothers collaboration failed to come to fruition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks