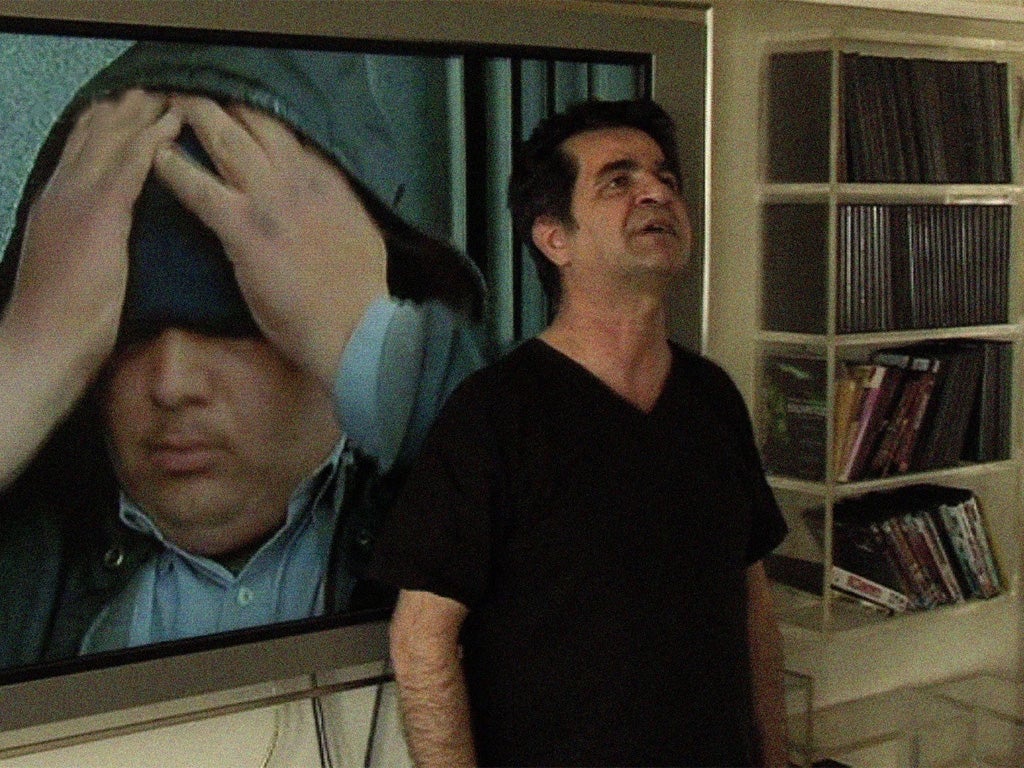

This Is Not a Film, Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb (U)

An Iranian film director banned from making movies and placed under house arrest has the perfect answer: a masterpiece about house arrest

Film-makers are forever being complimented for taking risks. As often as not, this means no more than casting Judi Dench against type, or attempting to fuse a romcom with a heist thriller. Really taking risks is another matter. Last year, the Iranian film-maker Jafar Panahi was sentenced by a court in his country to six months' imprisonment and forbidden to write or direct films for 20 years. Panahi, a supporter of Iran's opposition movement, was accused of working against the ruling system. Several of his films have been banned in Iran, and certainly tend to offer a critical view of life there. The Circle (2000) is an ensemble piece showing how the odds are stacked against Iranian women; Crimson Gold (2003) is a superb city drama about a disturbed pizza delivery man in Tehran.

Critics have sometimes, unfairly, ranked the realist Panahi below his former employer Abbas Kiarostami, who has special auteur cachet as a formal innovator. Panahi has seemed less experimental, until now. His new work plays mischievous games with our idea of what a film is – while being a very direct and compelling statement about his current plight.

This Is Not a Film is essentially a video diary, following Panahi through a day while under house arrest in his Tehran flat last spring, and contemplating his judicial appeal. Panahi isn't filming himself – that's the whole point, he's not allowed to. Instead, he's filmed – by the camera that his son, who's away, has obligingly set up, and by his friend Mojtaba Mirtahmasb (credited as co-author) who drops by to keep him company.

Left cooling his heels indoors, Panahi stands contemplating the city outside, heard as a hubbub of noises off. He talks on the phone with his lawyer, one of several unseen female presences in the film: another is a young neighbour who wants him to look after her yapping dog. He also feeds his daughter's pet iguana, Igi, a fellow prisoner in the "cell" of the Panahi home, but one who makes the most of what freedom he has – clambering over the director's chest, or scaling the back of the bookcases.

The day's main business, however, is making a film – or not making one. Mirtahmasb films Panahi while he describes his latest script, turned down by the authorities: a story about a young woman whose parents lock her in their home rather than let her go to university. As he maps out the locations in his flat, Panahi is at once expressing solidarity with people like the young woman, and describing his own claustration. He also shows clips from his own work. In one, a child actress is captured on film suddenly deciding she's had enough; she walks off, protesting: "I'm not acting!"

What a luxury that would be for Panahi, who has no choice but to play the lead in his own drama.

It's hard to know exactly what we're watching in this exercise. Sometimes Panahi and Mirtahmasb appear to be acting out a pre-scripted drama in documentary form, a formal conceit that offers the opportunity to mull over what it means to make a film. It's a topic that might have been merely navel-gazing – except that, in this case, Panahi's fate hangs not just on a philosophical but also a technical definition of his art. But at moments, his wry good humour subsides, and genuine fatigue and uncertainty seem to show on Panahi's features. The poignant thing about his and Mirthahmasb's enterprise is that they don't make a big deal about film-making being a matter of life and death: it's just what they do, and what else are they supposed to occupy themselves with? "When hairdressers have nothing to do," Mirtahmasb says, "they cut each other's hair."

This Is Not a Film premiered in Cannes last May after reportedly being sneaked out of Iran on a USB stick baked in a cake (a nice variation on the file-in-a-cake smuggled into prisons). Mirtahmasb has been arrested since, although is apparently now free, awaiting trial; while Panahi, who had previously been jailed, has had his appeal rejected. According to recent reports, he is currently free – and no longer under house arrest – but can be sent back to jail at any time. It's hard to know how the Iranian authorities feel about the international exposure given to Panahi's film, or not-film – and he surely knew when making it that he was taking a major personal risk.

The result is a superb piece of cinema, and something that's not cinema – passionate resistance, a humorous cri de coeur, a message in a bottle sent to the world, and a way for Panahi to keep his hand in.

As he says early on: "Somehow I'm making an effort." This spare, modest offering may not seem like much, but in terms of Panahi's life and future, and as a statement of faith in the power of the moving image, it's a work of staggering importance.

Film Choice

Euro-star Cecile de France gets in gear in The Kid With the Bike, the latest from Belgium's Dardenne brothers, superbly economical storytellers who draw all their dramatic material from a declining local steel-town. There's murder mystery with a dash of Chekhov in Nuri Bilge Ceylan's finest film yet, the sublime Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks