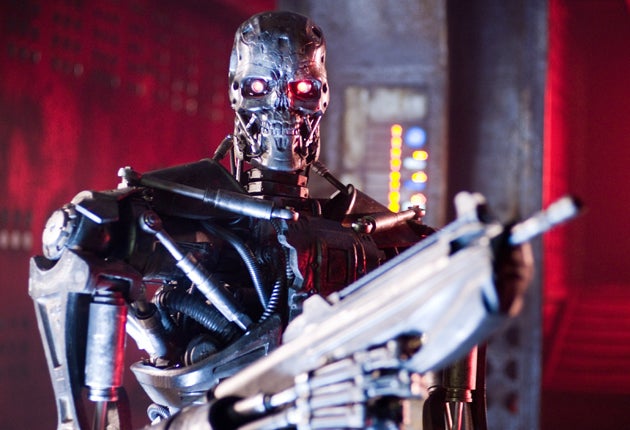

Terminator Salvation, McG, 115 mins, Cert (12A)

Arnie-type Terminators are in their infancy in this prequel-sequel gun-fest, but who cares? In McG's dull dystopia even humans talk like machines, and a never-ending war franchise means that ... they'll be back

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is it that makes us human?" ponders the closing voice-over in Terminator Salvation. "It's not something you can programme." It's certainly not, as proved by this fourth episode in the "Terminator" series, which is the most programmed and the most joylessly inhuman film I've seen in a while.

I feel rather bad about saying that, as I've long held faith with the belief that computer-generated cinema can sometimes produce true wonders. One film that sparked that faith, for viewers and film industry alike, was James Cameron's revelatory Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991 – can it really be that long ago?). Terminator 2 didn't just batter our senses with marvels, as so much CGI cinema has done since. Rather, it displayed a vivid sense of uncanny transformation: its android metamorphoses, from flesh to hard metal to mercury, were bizarre and genuinely novel visions.

What was marvellous about CGI cinema as Cameron practised it back then was its sense of things being malleable: its liquidity. But because digital images are manifestly immaterial, just dots of light on a screen, film-makers tend to compensate by over-emphasising the impression of solidity. That's what fatally weighs down Terminator Salvation. There's no magic or lightness here: this is a film of crashing machinery, booming explosions, seismic thunder (its real auteur, surely, is sound designer Cameron Frankley).

Terminator Salvation is a film that seems inadvertently to dramatise its own redundancy. It is set in a future in which machines have taken over and human agency is endangered: one way of describing this kind of digital cinema. The film's live actors are strictly playing support to a cast of killer robots and colossal mechanised engines of destruction: this is not cinema but ironmongery.

Bizarrely, Terminator Salvation would have to be classified as a sort of reverse-prequel to Cameron's original The Terminator (1984). In that film, a killer cyborg from the future travelled back to the 1980s to prevent the birth of one John Connor (or "Chan Kanna", as Schwarzenegger pronounced it), the future saviour of humankind. The Cameron-less Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines of 2003 had more backwards time travel, but Terminator Salvation is firmly set in the future, in 2018. Connor (Christian Bale) is already battling robokind, but the cyborg of the first film is still at prototype stage (hence a sudden and alarming cameo by a lumbering Arnie clone). So this is a prequel that takes place some 30 years after the original film.

As one character puts it, musing on temporal paradox – and presumably voicing the screenwriters' own anxieties of a sleepless night – "a person could go crazy thinking about this".

Alas, Terminator Salvation gives us little to go crazy about. The time-travel issue barely figures. Instead, a man from our age wakes up in the future, transformed. He is convicted killer Marcus Wright (Sam Worthington), who signs his body over to science before execution. Decades later, he wakes to find that the world has changed, and so has he. I won't reveal what's happened to him, except that his stamina holds up remarkably well for an executed man, and he's looking a little steelier around the chops.

Unlike Cameron's episodes, this Terminator dispenses with all vestiges of conceptual ingenuity: it's purely an affair of fire-power, and its most terrifying dystopian vision is of a world in which everybody talks like disposable action-movie muscle ("What day is it? What year? ... What happened here? ... I gotta get outa here"). Consequently, not only is it impossible to care about the characters, it's also hard to take seriously the very idea of human as opposed to machine values. At least the robots spare us the pulp talk.

Not that the humans seem very human anyway. That sometimes remarkable ball of actorly torment Christian Bale is nothing here but a tight-browed gladiator, lugging his blasters around and issuing commands in the same gravelly mono-bark he used in his notorious on-set barracking of the film's hapless DoP, Shane Hurlbut. Co-star Worthington easily outscowls him in any case, and at least makes little pretence of being other than a battery-driven Action Man toy with a sandblasted jaw.

The director is Charlie's Angels hack McG – or MCG as the opening titles print it, making him look like a corporation or a software programme, and he might as well be either. He brings the film neither urgency nor humour (sole gag: this time it's Bale who growls the deathless formula "I'll be back"). But McG is not entirely without credit: he and Hurlbut pull off one magnificent "impossible" shot early on, the camera whizzing in and out of a helicopter in flight.

Some of the robot design is interesting, too: not so much the Terminators themselves, their metal skulls looking like bikers' Halloween lanterns, but the new creations, titanic engines of war whose knees conceal detachable self-propelled motorbikes (Terminators, Transformers, who knows the difference any more?).

As post-apocalyptic landscapes go, the one envisaged here is bleaker than most, but that doesn't make it interesting. This particular genus of desolate, battle-scarred landscape has been standard in science-fiction cinema for a long time now, so it would be far-fetched to claim, as some fans surely will, that Terminator Salvation's deserts and dust-grey palette specifically evoke pictures of the Iraq war.

Even so, the film is horribly of its moment. Its vision represents not an authentic dystopian nightmare, just the thoroughgoing cynicism and weariness of the current Hollywood imagination.

Such vistas of infernal, unresolvable conflict arise not from real cultural anxieties, but simply out of the logic of the endlessly repeatable, associated with computer gaming. A story in which there can be no ending, happy or otherwise, ensures that things continue indefinitely, keeping gamers at their consoles and making endless movie sequels possible. Hence Terminator Salvation's image of ever-protracted, ever-bankable total war – a scenario that would appeal equally to fans of apocalyptic heavy-metal sci-fi and to Halliburton shareholders.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments