Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Werner Herzog, 93 Mins (U)

The cave paintings at Chauvet may be 32,000 years old, but Herzog, with his appetite for a challenge, brings them to dazzling life with judicious use of 3D

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The sepulchral tones of Werner Herzog always sound as if they're issuing from the world's deepest chasm – so it's only natural that he has now made a true underground film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams. This is an oddly workmanlike production, certainly by his standards. His recent Encounters at the End of the World, ostensibly a no-frills Discovery Channel travel- ogue about the Antarctic, broke off from its investigations to wonder whether there was such a thing as "a deranged penguin" (sure enough, Herzog found one).

Cave of Forgotten Dreams, however, gives us a subject so arresting in itself that, for the most part, Herzog keeps mum and simply observes. The subject is the Chauvet cave in France's Ardèche region, only discovered in 1994. It contains paintings 32,000 years old, the oldest yet unearthed, and they are breathtaking – dynamic, boldly outlined images of horses, rhinos and lions. There are also repeated handprints by an individual with a crooked finger, seemingly the first artist's signature.

Because of their fragility, the caverns are heavily protected, hidden behind a steel door, like a bank vault; that makes this a kind of heist movie, stealing the past from the bowels of the earth. Herzog was given permission to film under the strictest conditions, using only a four-man crew; they had to keep to narrow metal walkways, use small non-professional cameras, and brave high levels of carbon dioxide (all of which, you can bet, appealed to the director's fetish for difficulty).

In addition, Herzog decided to make the film in 3D. But the result is anything but a James Cameron-style extravaganza for Imax screens. Herzog's use of the medium is modest, intimate. The only nods to spectacle are a computer-generated 3D map of the caves, and the occasional swooping vista of the Ardèche gorges.

But Herzog's main concern is to give us a sculptural, tactile impression of the caves: as he films the walls close up, we sense their curvature. As he runs light over them, the surfaces bend, the animals undulate. The film proves – along with Wim Wenders' forthcoming Pina Bausch feature – that 3D isn't just for animation and sci-fi, but can bring an enhanced spatial aspect to material that deserves it. Here, Herzog makes the most not just of the paintings themselves, but of the lacy ripples of calcite on the ground, the stalactites that variously hang like vermicelli or ruched curtains. Because this is lo-fi 3D, more disconcerting things happen: the screen warps strangely, and parts of people's bodies fuse with the background. But such bizarre side effects only add to the overall immediacy.

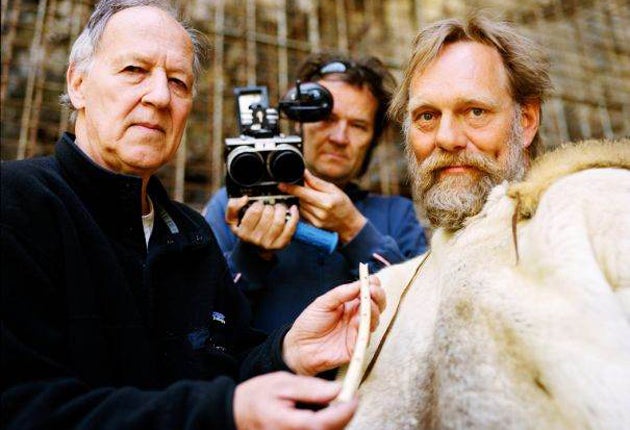

Herzog inevitably unearths some oddballs: the wonderfully named Wulf Hein, an archaeologist in (pre-)historically accurate reindeer fur, who plays "The Star Spangled Banner" on an ancient vulture-bone flute; and Maurice Maurin, a master perfumer who sniffs out hidden caverns (if only the film had been in Smell-o-Vision).

For the most part, Herzog's voice-over is matter-of-fact, no more outré than the standard Attenborough commentary. But eventually the Bavarian sage can't resist the lure of mysticism. Not surprisingly, he sees the Chauvet pictures as the birth of cinema. Imagining Palaeolithic man marvelling at the play of firelight on the cave wall, Herzog cuts in footage of Fred Astaire dancing with his own giant shadow; you find yourself imagining Cro-Magnons dancing cheek- to-cheek in top hat and mammoth fur. In the epilogue, Herzog finds albino crocodiles living in an artificial biosphere on the Rhone. He wonders what they'd make of the cave paintings (I suspect they'd wonder why no reptiles were featured), then muses, "Are we today the crocodiles who look back into an abyss of time?"

While we ponder this quintessentially Herzogian imponderable, it strikes me that there's only one serious mistake in the film. A speleologist (cave expert) asks the crew to listen to the silence of the caves, then to the sound of their own hearts. We get a few moments of absolute stillness – before, thumping away on the soundtrack, in comes a throbbing heartbeat, soon joined by the spurious awe of Ernst Reijseger's score, all cello, organ and celestial (or rather subterranean) choir. Can it be that even Herzog is afraid of a few moments' silence on screen?

Overall, there's less of Herzog here than in many of his documentaries – this is a serviceably engrossing study of a fascinating subject, rather than a full-blown visionary essay. But I like the musings on cave paintings as proto-movies; and perhaps 3D itself might be seen as an instrument of mystic revelation, for which we don goggles to partake of a ceremony a little stranger than the norm. Not that there's anything new in the idea of the cinema as a cave. It may be a cave, alas, of largely forgettable dreams – but then Herzog's reveries, even at their least extravagant, are always an exception, and it doesn't take an albino crocodile to see that.

Next Week

Jonathan Romney delves into dreams and delusions, Hollywood style, with Zack Snyder's CGI epic Sucker Punch

Film Choice

Richard Ayoade, from Channel 4's The IT Crowd, makes a persuasive directing debut in Submarine, a comic tale of teenage angst with spiky adult support from Paddy Considine and Sally Hawkins – but young talent Craig Roberts steals the show. Meanwhile, in thriller land, Matthew McConaughey stars in The Lincoln Lawyer – old-school, hard-boiled and sleekly entertaining.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments