William Shakespeare 400th anniversary: The Bard's works on screen - the hits and the misses

An estimated 500 adaptations of his plays were made in the silent era alone; since then, there have been westerns, sci-fi pictures, B-movies, gangster films and samurai versions of the writer’s work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You just can’t escape Shakespeare on screen. An estimated 500 adaptations of his plays were made in the silent era alone. Since then, there have been westerns, sci-fi pictures, B-movies, gangster films and samurai versions of the writer’s work. He has inspired several musicals, lots of comedies, teen romances, beatnik dramas and some horror films too. The real mystery is why so few of them have been any good.

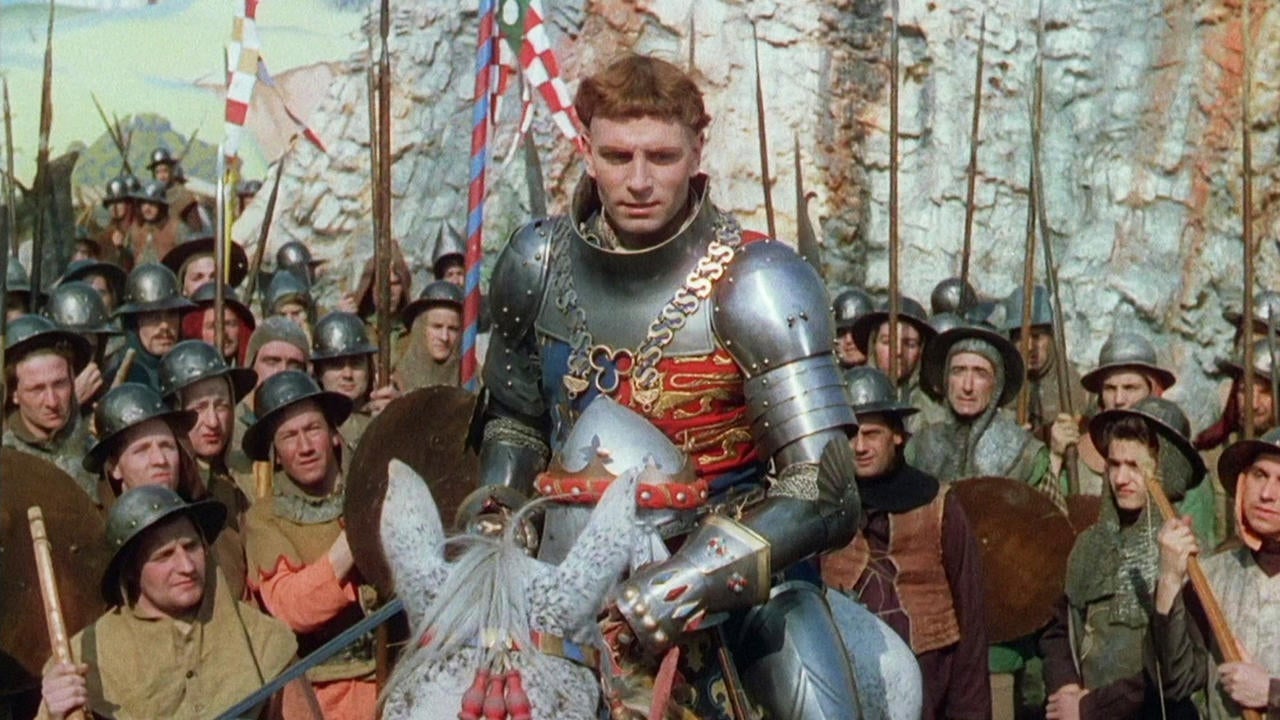

David Thompson’s All The World’s A Screen: Shakespeare On Film, a BBC Four Arena documentary to be broadcast this weekend, makes the argument that Laurence Olivier’s wartime Henry V (1944) was the first really decent Shakespeare movie. “It took 50 years for his work to be turned into a truly cinematic experience,” the documentary tells us. Olivier himself was convinced that his film eclipsed everything that had come before it. He had finally found a way to make Shakespeare cinematic. It helped that the film had an obvious topicality. It was a nationalistic, morale-boosting war movie which found a very receptive audience in wartime Britain.

All The World’s A Screen includes black and white footage of Olivier in military uniform, doing his bit for propaganda, giving a speech to the armed forces. He declaims his lines in exactly the same way as the soliloquies in Henry V.

Earlier Shakespeare adaptations had been hamstrung by their piety. They were often very stagy. In the early days of the Twentieth Century, several of the great actor-managers took their chances in front of the film cameras - but with very variable results.

Sir Herbert Tree appeared in King John in 1899, one of the very first Shakespeare films. This was very definitely a miss, a determinedly eccentric endeavour, shot on London’s Embankment and recreating a stage production. Tree himself later admitted it was “entirely without meaning except to those who were perfectly familiar with the play and could recall the lines appropriate to the action.” Tree was later to star as Macbeth for the great American director, D,W. Griffith, and again struggled to make sense of the fact that no-one could hear the soliloquies.

Griffith had also directed an early version of Taming Of The Shrew (1908) boasting a very lively performance from Florence Lawrence, the “first movie star.”

Back in Britain, Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson, “the supreme Hamlet of our time” as he was called, made a film version of Hamlet in 1913. An actor known for his delicate gestures and beautiful speaking voice, Forbes-Robertson didn’t make any concessions to the cinematic medium at all. Although the film was silent and shot on location, he still recited his lines as if he was centre stage at the Old Vic. That film was most certainly a miss, albeit a historical curiosity.

The argument that silent versions of Shakespeare were undermined because the audience couldn’t hear the verse doesn’t really stack up. Akira Kurosawa’s Throne Of Blood (1957), inspired by Macbeth, disregarded the verse entirely and transplanted the action to feudal Japan. What Kurosawa demonstrated was that there was primal intensity in Shakespeare’s storytelling that had nothing to do with the soliloquies. This intensity was also evident in Ran (1985), his astonishing version of King Lear in which an ageing Japanese warlord tries to divide up his kingdom and unleashes chaos and destruction as a result. You can draw a line from Shakespeare through Kurosawa to Star Wars. George Lucas’s characters and plot-lines aren’t so different from those found in Macbeth and King Lear.

There have been many bad and misconceived versions of Romeo and Juliet. The BBC Arena documentary shows clips of one starring a 43-year-old Leslie Howard as Romeo. (Howard looks more like a dashing home counties commuter than a lovelorn adolescent from Verona.) Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 Romeo And Juliet works brilliantly for the same reason that Olivier’s Henry V hit the mark. It is a film made for its time. Zeffirelli took the common sense decision actually to cast good looking teenagers (Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey) as the young lovers and then to encourage them to give naturalistic, Method-style performances. It was a film that was both true to its source material and that caught the mood of the hedonistic late 1960s.

One reason Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971) feels so chilling is the echoes it carries of the director’s own life. He was enraged that the press tried to draw connections between the murder of his wife Sharon Tate by members of Charles Manson’s “family” and the bloody events in Shakespeare’s play. Nonetheless, he did acknowledge that the film reflected what he had experienced as a child in Nazi-occupied Poland. “When they (the Nazis) were raiding houses, you always heard those screams everywhere - on the second floor, the ground floor. It was like stereo in your apartment. You had people screaming…either they were beating someone or shooting someone or dragging someone out. I remember that.”

To many critics, the very greatest Shakespeare screen adaptation is Orson Welles’ Chimes At Midnight, his “lament” for a merrie England of decency, chivalry and humour that may never really have existed. Falstaff (played by Welles himself) is the unlikely hero of the film, whose script is pulled together from five different Shakespeare plays. It is not a smooth piece of filmmaking at all. Like almost all of Welles’ movies, it was dogged by difficulties with financiers. What it possesses, though, is a sense of innocence and nostalgia that is quite magical.

If you can’t watch Chimes At Midnight, maybe look out for Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. As that film reveals, snobbery about the bard extends even to the further reaches of the galaxy. As the Klingon Chancellor Gorkon (David Warner) insists, “you’ve not experienced Shakespeare until you have read him in the original Klingon.”

All The World’s A Screen: Shakespeare On Film screens on BBC FOUR on Sunday. The 30th-anniversary digital restoration of Ran is released on DVD & BLU-RAY 2 MAY.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments