The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Robert Oppenheimer: The true story behind Christopher Nolan’s biopic about ‘the father of the atomic bomb’

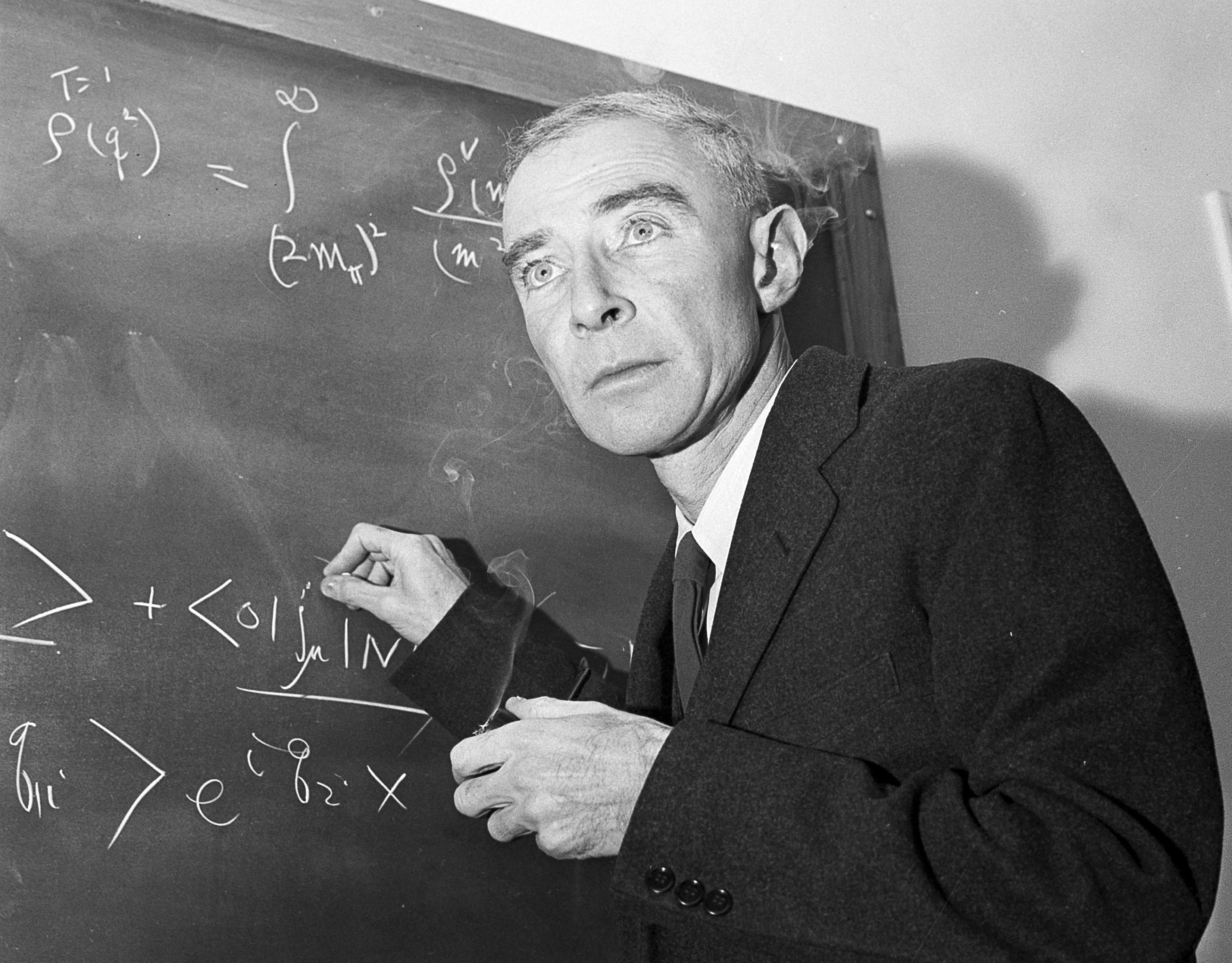

Real-life scientist behind the atomic bomb has a complicated legacy in America

Christopher Nolan’s long-awaited new blockbuster Oppenheimer is out in cinemas this week.

The film starring Irish actor Cillian Murphy in the titular role promises to tell the story of American scientist J Robert Oppenheimer and his role in the development of the atomic bomb.

It is partially based on the Pulitzer-Prize-winning 2005 biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer written by Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin over a period of 25 years.

“Celebrated in 1945 as the ‘father of the atomic bomb,’ nine years later he would become the chief celebrity victim of the McCarthyite maelstrom,” Bird wrote in a recent opinion piece for The New York Times.

Oppenheimer is the first film to properly tackle the scientist and his legacy, which was marred by a controversial 1954 hearing that resulted in his security clearance being revoked.

Who was J Robert Oppenheimer?

Oppenheimer was born into an affluent German-Jewish family in New York City. His family’s art collection included original works by Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh.

It became apparent at an early age that Oppenheimer’s academic ability outstripped those of his peers and he entered Harvard University aged 18 where he graduated after just three years summa cum laude (with highest praise).

However, he struggled with his mental health. During his time at college, he expressed suicidal thoughts and, while pursuing a graduate degree at Cambridge University, deliberately left an apple, poisoned with laboratory chemicals, on his tutor’s desk.

By the outbreak of World War II, though, Oppenheimer had transformed himself into a respected professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and had already made numerous, significant contributions to science.

During his time at Berkeley, he fell in love with Jean Tatlock (played by Florence Pugh in Oppenheimer), the daughter of a Berkeley literature professor and a student at Stanford University School of Medicine. She was a member of the Communist Party, which later became an issue in his security clearance hearings.

It’s been confirmed Murphy and Pugh have scenes of “prolonged nudity” together – a first in Nolan’s filmography.

They broke up in 1939 and, a year later, he married Katherine (”Kitty”) Puening with whom he had two children.

During their marriage, Oppenheimer rekindled his relationship with Tatlock and the two had an affair. She later committed suicide in 1944.

The Manhattan Project

In 1941, two months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D Roosevelt approved a programme to develop an atomic bomb.

A year later, Oppenheimer was recruited by the National Defense Research Committee to research the building of an atomic bomb.

That September, General Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon in the film) took over as head of the Manhattan Project (named after its inaugural offices in lower Manhattan) and selected Oppenheimer to head the project’s secret weapons laboratory.

For three years, Oppenheimer and a huge team of scientists worked towards the creation of an atomic bomb out of a military laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Their work culminated in the first nuclear detonation in history, known as the Trinity test, on 16 July 1945. In an interview conducted years later, Oppenheimer claimed that a line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, had come into his mind during the detonation: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

A month later two of the bombs developed by the Manhattan Project were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, killing approximately 200,000 people, the majority of whom were civilians.

On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender.

The security hearing

After the project’s success, Oppenheimer continued to act as a nuclear weapons consultant for the US government; however, he warned against their devastating capabilities.

In a 1953, speech he likened the nuclear capabilities of the United States and the Soviet Union to “two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life”.

In December of that year, during the Second Red Scare in the US, Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) Chairman Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr in Nolan’s film) told Oppenheimer that his top-secret security clearance had been revoked and insisted on his resignation.

However, the scientist refused and insisted on defending himself at a highly-publicised security hearing, which he lost amid public humiliation.

Numerous sources have suggested that Oppenheimer never recovered from the incident.

The New York Times wrote in his obituary: “This bafflingly complex man nonetheless never fully succeeded in dispelling doubts about his conduct.”

Attempts were later made to repair Oppenheimer’s image – in 1963, President Lyndon B Johnson presented Oppenheimer with the Enrico Fermi Award, the AEC’s highest honour.

A chainsmoker, Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in his home in Princeton in February 1967.

In his piece for The NYT, Bird wrote: “It is my hope that Christopher Nolan’s stunning new film on Oppenheimer’s complicated legacy will initiate a national conversation not only about our existential relationship to weapons of mass destruction, but also the need in our society for scientists as public intellectuals.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks