Amitabh Bachchan: Meet the biggest movie star in the world

Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan has the combined star wattage of Brando, De Niro and Eastwood, and is loved by millions. His latest film plays with the idea of extreme adulation, which comes as no surprise to Sarfraz Manzoor

If you haven't heard of Amitabh Bachchan, I feel rather sorry for you. He is, after all, the greatest actor Indian cinema has produced and his films are some of the greatest you are ever likely to see. Bachchan has been a phenomenon for more than four decades and at 72 he is still making films that excite and surprise audiences around the world.

His latest, Shamitabh, is about a young actor who achieves top-billing by "borrowing" the overdubbed voice of a down and out, played by Amitabh (hence the "sham"); and of course it gives full range to his rich, commanding baritone, which has transfixed audiences for more than 40 years.

But it's also a meditation on identity and the nature of fame and fortune – asking audiences to examine their own role in the relationship between idol and fan – and, arguably, a sign of the growing sophistication of the Indian film industry. And it is a sophistication that has been in part affected by Bachchan, who is such a huge name that the industry has had to mature with him, changing its focus to fit in with his own journey through life. And you can't be a bigger star than that.

How can one give an idea of his stature to the uninitiated? By explaining that the actor possesses the combined star wattage and potent aggression of Brando, De Niro and Eastwood? Or that he has more than 13 million followers on Twitter, and a separate Wikipedia page devoted only to the awards he has won? There's the story of the leading Indian film director who suggested to me that the Indian film industry should be called "Bachchan" instead of Bollywood. But none of those facts can fully convey the adoration accorded to the man whom his fans call "The Big B".

Rather, it may be best to pose a question: is there any other actor who, were he to sustain a serious injury while filming, could prompt his fans to offer the sacrifice of their own limbs to save his, or lead one man to walk 300 miles backwards in divine supplication?

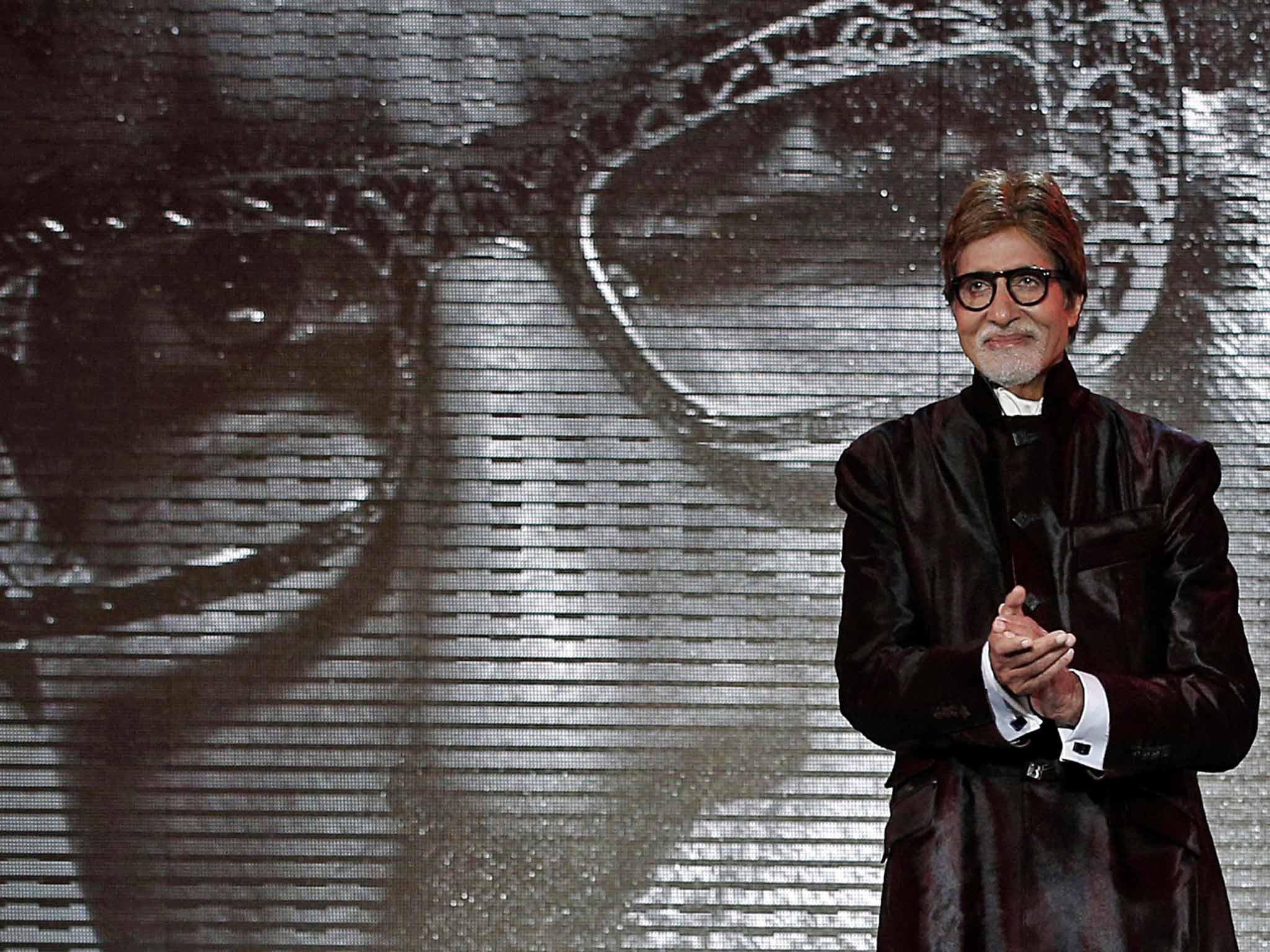

Amitabh Bachchan is in a league of his own; just don't tell him that. With his chestnut hair, white goatee and, behind his glasses, a surprisingly unlined face, he is relentlessly and almost pathologically humble (see interview, right). He will tell you it was all a happy accident; that it was all down to the writers and the directors and nothing to do with him. But this humility obscures the truth that Bachchan is now working with directors who actually grew up worshipping him.

Amitabh Bachchan occupies this hallowed place in the Indian film business – and in Indian culture – because of the decade of seminal films that he starred in starting with 1975's Sholay (a movie that is often voted the greatest Indian film of all time). His films – which were intended for, and hit home with, working-class audiences who were desperate for escapism – were also reflective of their time.

During the 1970s, India had fallen into a State of Emergency, introduced by then Prime Minister Indira Ghandi, and in these films Bachchan's characters stood up for the ordinary man against the injustices of the establishment. During this period, he would be filming up to 12 movies simultaneously; in some he played double roles; and in one film he portrayed a father and both of his sons. He was a mesmerising presence: he made you believe that one man was genuinely capable of changing the world.

If it was wish fulfilment for those watching in India, they offered something else for those of us watching in Britain. In the early 1980s, my family would watch Indian films most weekends.

My father would rent a VCR player for £5 and we would choose three films to watch. They would almost always be Amitabh Bachchan films. His films helped bridge the generations: no matter what else we disagreed about in my family, when Bachchan was on the screen, we would all watch as one, united.

Bachchan also mattered because this was a time when there was so little representation of Asians on television. Many of us, including me, were struggling to find reasons to be proud of our heritage. Bachchan's hyper-masculine heroism and aggressive idealism showed us there were other ways to be Asian on screen than as a victim. And if a Bachchan film comes up on one of the satellite channels, the chances are I will still watch it.

It could have been very different. While filming Coolie in 1982, he was seriously injured during a fight scene, and flown to hospital, where he hovered between life and death. Indira Gandhi made a visit to his hospital bed and doctors gave him only a 10 per cent chance of surviving. While he remained in a coma, Indians prayed for him in churches, temples and mosques, and others fasted.

When he did recover, Bachchan took to appearing outside his Mumbai home to greet the thousands of well-wishers who had gathered – a tradition he maintains to this day – and the debt he feels may explain why Bachchan is, by his own admission, a compulsive user of social media. On Bachchan's blogs and in his tweets one can read his unfiltered thoughts on the business of film promotion: "zombied & stone deaf to any conversation or questioning ...robotic responses, effortless smiles and guided repartee ...#Shamitabh" reads one bracingly honest recent tweet.

If he was a phenomenon in the 1970s and early 1980s, in the past decade he has become a brand and the head of a dynasty: his actor son is married to former Miss World Aishwarya Rai, and his name endorses countless products.

There was a time, though, when Bachchan's star was on the wane. In the mid-1980s he was persuaded to enter politics by his friend Rajiv Gandhi, a decision generally accepted to have been disastrous. He took a break from acting and during that time forayed into business ventures, all of which bombed.

He returned to movies, but trying to play an angry young man when he was in his fifties didn't end well. He needed a reinvention – which came in 2000, when he became the host for the Indian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? The quiz show turned out to be a massive hit and Bachchan became the highest paid television star in Indian history. It returned him to national prominence, revived his film career and provided the inspiration for the book that Danny Boyle adapted into Slumdog Millionaire.

The latest act in Bachchan's career has seen him playing very different roles to the ones that made him famous. Those he took in the 1970s and 1980s were rather limited, but in recent years he has played everything from a rapper to a teenager, a ponytailed chef to a 60-year-old man who falls in love with a teenage girl

Given that he is now in his seventies, with a back catalogue of more than 180 films and more money than he can spend, one has to wonder why he still works so hard. As he said in our interview: "I am insecure about tomorrow. Will I get another job, what will I do and will it be appreciated?" But this insecurity seems so unjustified that one has to ask if it is genuine or a role he has taken to playing.

Just as Bob Dylan – who knows a thing or two about being idolised – took to claiming that he was just a song and dance man, Bachchan likes to pretend he is just a jobbing actor who got lucky and worries about his next gig. It is clearly, ridiculously, not true, but it is perhaps a necessary delusion: the only way a man can withstand four decades of sustained mass adoration and remain anything close to sane.

According to Amitabh: the star in his own words

SM: You're the biggest name in Indian film history and everyone acknowledges it apart from you – why is that?

AB: Actually the writer is most important. They dictate the terms. The director tells us what to do and where to stand. Someone comes to dress you up, someone else comes to do your make up and all you do is deliver your lines. It is a huge combined effort and our contribution is very minimal.

SM: I'm not sure I agree: those films worked because of what you brought to the role. On screen, you always exuded immense charisma, but is it true that you are actually rather an introvert?

AB: It's frightening to be facing an audience. There is always the fear of what they think of you, what they are saying about you. But so long as we are performing in the isolation of the studio and don't have too many people looking at us, we manage.

SM: Your films are repeated on television all the time. Do you ever find yourself flicking through the channels and landing on one of yours?

AB: I do sometimes watch them when they are on television. I usually start looking for all the faults I made.

SM: Indian films are often hugely dramatic: they are fun to watch, but how does it affect an actor to be playing such parts?

AB: We play many emotions in our careers, emotions that in real life we would perform just once. For example, my character has died in about 10 films, so you have to keep searching for different ways to do it!

SM: You've had great success in film but have also known failure. Would it be true to say that, although your reputation was made on film, it was rescued by television when you decided to host Who Wants to be a Millionaire?

AB: Yes. Everyone thought I was committing hara-kari, but it was essential for me to do something. I was facing bankruptcy, court cases, creditors, a failed company and a failed career.

SM: Staying with television, in the West, with shows such as Mad Men and Breaking Bad, that seems to be where the action is. Can you imagine a time when Bollywood is usurped by television?

AB: Well, there has been a vast explosion in television. There are 800 channels with content from around the world that is qualitatively better than what we get in our cinema. This has offered healthy competition, as Indian cinema wants to compete with the West. The advantage of TV is that there is a greater span of storytelling, and you have more time to develop a character. So, TV is a very exciting proposition, and I think we will get there. Eventually tastes will change.

SM: After your life-threatening accident during the making of Coolie, so many people prayed for your recovery. That must have been hard to process...

AB: I try to find ways to express my gratitude. My [public interactions] remain a happy debt which I am fond of carrying. It bears the love and affection of the people, and is a wonderful opportunity to hear and feel the fans who have loved my work.

SM: The roles you did in the Seventies and Eighties were quite narrow in range. But in your recent films, including Shamitabh, you are really expanding your range. Do you think you have become a better actor with age?

AB: I have had greater opportunity to do things that are different, and this comes with age. I can't be playing the leading man, so expectations become lower and I can take more risks.

SM: You've made more than 180 films. You must feel you've done it all. Does film-making still excite you?

AB: I get excited every day: it is wonderful, and it is inexplicable. It would be a horrible day if I was to think, I have done it. It would kill any creativity I possess if I was to be satisfied. Any creative person should never be satisfied with their work.

SM: Don't you think you've done enough to be satisfied with your work and not to worry what people think?

AB: I am insecure about tomorrow. Will I get another job? Will it be appreciated? I will pursue acting for as long as I have a face and body that is acceptable to the people but I still worry that if I don't do better tomorrow, it will all go away.

Shamitabh' is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks